From your experience, who is the most interested director in sound?

I’ll answer the question I wished you had asked. It’s the director who understands that sound, from the very beginning in pre-production, includes his/her sound artists as advocates for the idea at hand. This director hugs the sound artists inside the circle of trust recognizing their creative contribution. This director understands that sound is an integral part of the creative palette, beginning with the essential capture of performance, effects, and environment in ways that reveal character and tell the story. This director takes his Sound Mixer on his tech scouts to witness and join the creative power flow emerging with the DOP, AD, and other team members.

What is your view of the Sound Department’s artistic contribution to each project?

It is an experienced reality for many of us in our esoteric art form. What we do is so invisible and misunderstood, especially with how we function on the set. I don’t mean this in a disrespectful way. There is great misinterpretation by those who work alongside us every day. Very often, they are unaware of exactly what we’re doing. Our collective voice must reposition this disconnect in a proportionate way. Fortunately, this is in play in certain quarters these days, but it’s still a major challenge to the recognition of our craft.

I don’t use the “bad-for-sound” description of a challenge as it usually triggers a territorial interpretation of what I’m saying. Instead, I engage when choices need to be made. I explain the issue, with the fewest words possible, placing in the director’s hands, the options before us. If it’s the director’s idea at issue, it’s much more effective to speak forthrightly, in terms of the competing elements and the range of solutions available. I won’t cut unless I’ve been given that authority by the director in advance. I don’t want to anyway, as there may be other essential elements within the shot not sound-related. This must be a part of our trust relationship. If a 2022 Airbus 330 jet flying overhead occurs during an 1870 dialog scene, I will bring it to the director or AD’s attention in the moment.

Some people who have the creative and financial authority of directing and/or producing are not necessarily knowledgeable about production sound and its use as a part of their skill set or creative palette. This can certainly be a problem.

What is the best way to communicate this?

How we communicate this has multiple levels to it. If you frequently come as the messenger of bad news, you can erode your credibility. We’re there as an advocate for directorial intent and telling the story, Our only agenda is to help it be better. My position is, it’s never about my sound, it’s about the sound. It is about serving your project. If the production wants to make a decision that is going to postpone the resolution of the problem; it’s their prerogative to do so, and I’ll support that even if I think it’s not the best solution, as long as I’ve been clear about the competing elements in a timely fashion.

My prejudices must stop at the door. A leader takes information and recommendations from the team and then makes a decision. This is the responsibility of the director. But how you present where your concern comes from should redirect the attention from yourself to the “we-together” problem solving of the project. My ego is intact, but it’s directed toward serving the project, not about protecting my “work” or worry of being criticized in my absence, I work at defusing the notion of bad production sound by establishing my credibility.

I aggressively maintain a collaborative relationship with the Supervising Sound Editor and the Re-recording Mixers in pre-production, and then through production. I want that open line of communication, not just for challenges and problems, but for creative contributions that together, we interpret the intent of the director.

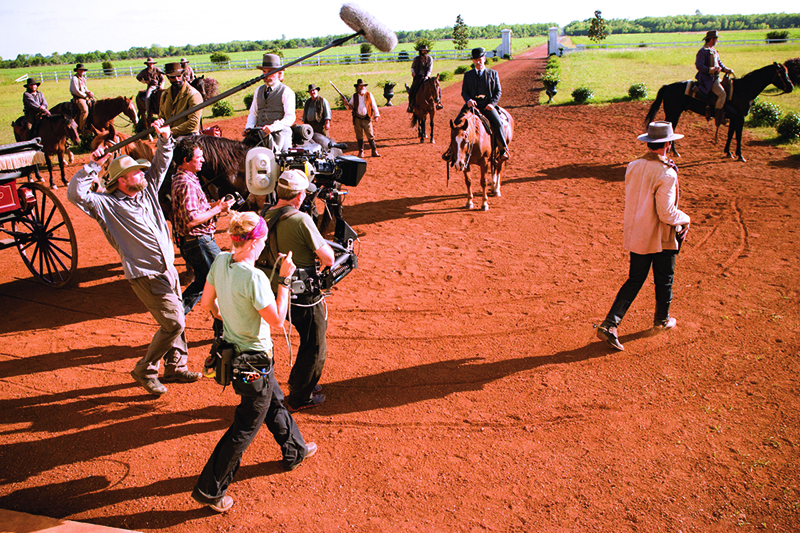

I did a film called Cowboys & Aliens with Daniel Craig and Harrison Ford. Harrison created a voice for that character that he turned on and off like a switch. Cameras on, he’s in that voice, it’s sort of low and gravelly, very consistent. He was his own reference. That voice impacted my choices for tonality, which mic and its placement I would use for him and how I would mix his voice into the scene. This is an example of being aware of a significant actor contribution, and how I was collaborating with and protecting that contribution.

That’s the mindset I have when I’m dealing with this idea of “Okay, we want to create sound that tells this story, we’re really with you.” Then on the day, we’re chasing the sun up the hill. It’s panic vision and f**k sound and we’re off and running. I try to be a buffer to that impulse. Often the First AD is an interpreter of a director’s decision-making prerogative. The First AD has more than one agenda. Surface-wise, they’re the director’s advocate and a conduit of information to the rest of the crew. But they’re also part of production; they are shooting a schedule and making their day has financial implications for them. They get bonuses for coming in under time and under budget. One could argue that this is a conflict of interest, but nonetheless, there it is. Or they may have very deep conviction that they know exactly what is and isn’t okay without consultation. We’re there to be the “DPs of Sound,” if you will, on the set. Our responsibility is at this level.

Some mixers remain silent out of fear of alienating themselves with the ADs and the Director.

To me, this way of thinking is a strategic mistake. There’s a third way. You don’t need to be in an adversarial posture over the challenges created by competing elements. Moviemaking is all about competing elements. Every day, every shot, there’s some kind of element that seeks to be dominant in the shot. It’s not up to the Department Head or the mini-department heads to take it personally. The higher up the food chain you go though, the less frequently that occurs because they’ve been seasoned, they’ve been experienced. They understand it’s not just about them, it’s about the project, serve the project.

So, if you’re challenged by an element that has not been fully thought through and that is damaging other key elements, that’s a situation that could possibly have been solved in advance, but then…

If it isn’t, on the day, on the fly, in the moment, you, together, collaborate on a solution (if there’s one to be found). On a big movie, it’s probably five thousand dollars a minute of shooting time to run a two-hundred-million-dollar budget! You miss ten minutes and that’s fifty grand. You’re already stepping into a schoolteachers’ annual salary for those ten minutes.

So, how do we transcend that conundrum?

A: Become deeply invested in anticipating.

B: Become deeply skilled in interpreting the truth of the moment, not what everybody thinks what the moment will be, and

C: Have an armful of potential solutions for that moment in a very short period of time.

That means having more than one game in play simultaneously, most of the time.

The most important issue is how you are communicating these concerns?

My partner, Patrushkha Mierzwa, says, “When you come up against a challenge … never describe it as a ‘problem.’ “We don’t have a problem, we have a situation, and these are the competing elements, and here are the solution options. We need to decide what’s the best solution for this, whatever that range may be.”

It’s often our responsibility to make clear to people who do not understand what we do to not jump to a conclusion about how long something will take to do. We may have a much better solution that’s actually equal or less in time than the solution that they leap to in their mind. It’s up to us to be able to say, “This will take thirty seconds. This will take four minutes. This will take…” Whatever they need to be soothed in their anxiety about the time lost, and then to perform within the parameters close to your estimate, because you have the experience of how to do that. It’s in your repertoire.

When a DP needs to add another light, and there’s a ten-minute interval, it’s OK. But when our department asks, we sometimes hear, “We have no time.”

In The Godfather, Mario Puzo reiterated an ancient Greek saying: “The fish stinks from the head down.”

If you’re working with a director in control of the production priorities, and you’ve been successful being included in his/her “circle of trust,” then the director can see what you’re contributing towards their personal gain or loss for their work. If this can happen, then you will have an ally in clarifying what does and doesn’t matter. Of course, you have the responsibility to hold up your end by being good enough to solve it.

Often as not, we have the autonomy to creatively solve things that our non-sound colleagues may be clueless about, and I don’t mean that in a disrespectful way.

I’ve done more than one hundred fifty projects, primarily features, but some television projects. Most directors that I work with will have ten to fifteen projects in the scope of their careers. Does that make them less experienced than me? On one level, yes. But on another level, no. They are successful in those careers by having unique and capable voices and skill sets to manage creating a film. It’s unfortunate but the reality is very little is being taught about the sound arts to film students.

It has become our responsibility, in that early stage of pre-production, to establish our bona fides as a full contributing creative partner, as an advocate for the director’s intent. You embody that by the way you operate, by how you perceive each and every day, shot by shot. The precision of the words you use is your passport to inclusion.

We’re in a public debate right now in our community over the place and the hierarchy that the production team has. There are many of us who don’t recognize the value of their own contribution. It’s stunning, but it’s really true. “I’m just there, I record, I go home, that’s my bit and that’s my gig,” versus what is it that I’m doing that is best serving the idea here at hand? Who is this character? How is the audience supposed to experience this character? Is the character evolving over time through the plot? What am I doing that’s supporting that arc, the way depth of field, the way focused placement, the way tonality, composition, color, exposure? We have similar, not exactly analogous, but similar tools in our toolkit that engage in those pieces of telling the story.

What is the line of communication? Is it always going through the First AD primarily, and when do you talk directly to the Director?

I don’t have a very in-depth ideology in terms of words, but it’s very deep in terms of its purpose. I call it the ID ideology. “It depends.” Who are they? What’s their point of reference? How do they behave under load and what’s their perspective on what they do and what you do and how they interact?

The AD and the Director.

Is it a weak director? Is it a strong director, but weak in technique? Is it a director, strong in technique, but weak in philosophy, afraid of their actors? They often try to hide their fear of the actors by over-engagement. Do they feel under assault? Many directors are in abject terror from day one, or even prior to day one. There are two groups in the director community; those that have established their autonomy by success in the market and success in the critical world, and by their repeated engagement by major funding sources for their work.

Then there’s the other group who are still clawing their way to some degree of career stability, but are most often surrounded by a committee of second-guessers who are there with good intent and under great levels of compensation, by the way, to protect the director from themselves and to validate and justify their purpose.

Many TV shows have 10, 12, 15, 18, 20 people with the title of producer, and they’re mostly writers, but they’ll sit at the set in a chair watching a monitor of the scene with headphones on and on their cellphones, and they’re pulling down six, seven figures a year to do that. Meanwhile, we’re out there actually making it happen for far, far less. So that interferes with the director’s progress to mature into a skilled confident creative person.

For me, the best strategy has been to always approach the work as a filmmaker, akin to musicians in the orchestra. First, self-identify as an artist with a special instrument, then apply this instrument to telling stories with film through sound. We interpret directorial intent through emotion and tonality. We connect the characters to the audience. Every artist contributing to a film is a technician with their medium. We are as well. We make many creative decisions every day. We interpret and capture performance in context to story arc, character arc, and directorial intent. We do this in collaboration with the other film artists, above and below the line. We come together to tell the story. Nothing less…