Notes on the Production Sound for The Fabelmans

by Ron Judkins

Back in April of 2021, while working in Los Angeles on a project for Disney, I started hearing rumors from the crew about a Steven Spielberg project that was in the early stages of coming together for later in the year. At that point, I hadn’t worked with Steven since The BFG in 2016, so I wondered if I would be on the call list for an LA-based production. I don’t know about the rest of you, but sometimes it seems that the only real feedback we receive from a producing group about our work is that we get a call from them to bring us back the next time around.

But first a bit of context.

When I was in my late twenties and first starting out, one of my first real jobs was to take day calls at Universal Studios—working on the lot when a production mixer would need a brief replacement, or a day of pickup shots would be added to a sitcom. They would call me the night before. I would always be quite excited, and of course as a novice, I was scared to death. Boom Operator Bob Jackson and I would go in early on those days and walk from stage to stage and try to glean what was going on with the various shooting crews. Bob had been in the business longer than I had, so he was trying to bring me up to speed and to show me the ropes. But at Universal, we would see these decrepit old sound teams, boom operators collapsed onto five-step ladders, mixers huddled over Perfectone mix panels, and we would think—oh my god, when we are their ages, we do NOT want to be doing this anymore! But then the years go by, and the business kind of gets under your skin. That place where the camera is rolling and the actors are performing is to me one of the most magical places in the universe. I’m actually probably a bit older now than those old guys we were aghast at seeing working at Universal, but I still absolutely love the set and the process of filmmaking.

Since those days, I have been lucky to have worked on sixteen movies with Steven Spielberg, beginning with Hook in 1991 to last year on The Fabelmans. Each has been unique, with its own set of joys and challenges. I have often felt that with Steven, the entire production crew is often asked to work slightly beyond the scope of their normal abilities. In the moment, this can be intensely stressful, but is ultimately gratifying as you feel your capabilities and expertise expanding over time.

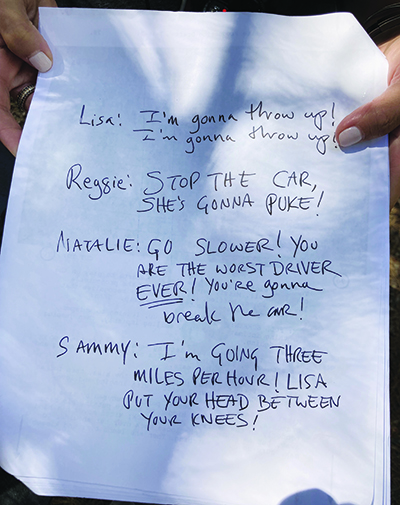

As an example—when we were filming Saving Private Ryan in Ireland, the landing craft scenes at the beginning of the film had been scheduled to be filmed on stage with dump tanks and the landing craft mounted on pneumatic rams for motion. But toward what we thought was the end of a day filming on the beach near Cork, a storm was approaching. Steven decided to shoot the major landing craft scenes right then and there. The weather would provide a dramatic background to the filming. We only had a forty-five-minute window to get the entire scene in the can before the storm would arrive in full fury, so we raced to haul camera, grip, and sound gear onto the hero landing craft.

There was no time to consult the script, so as I climbed on board I asked Steven, “Who is going to talk?” His reply, “Everyone!”

I hunkered down with a mix panel and recorder set on apple boxes. To be hidden from the camera, I was under camouflage nets, and I was being jostled and kicked by actors in combat boots, full battle gear, and weaponry. The camouflage nets had been hastily pulled from the beach, and were caked with sand and grit which filtered down onto me and the sound gear. The seas were getting quite rough as we started filming, everyone just trying to hang on, and waves started coming over the bow of the landing craft. I grappled with the gear to try to keep it above the rising water in the bottom of the craft. Bob Jackson stood next to Mitch Dubin at the handheld camera, and cued the boom at whoever was speaking. It was a high-energy scene and the actors were shouting to be heard over the roar of the engines and seas. But in the middle of a take, I noticed the overload lights starting to flash on the right side on my Sonosax mixer. Despite my efforts, it was getting wet. When I had a second, I quickly re-patched Bob’s mic cable into an input that I thought still might be dry—and I prayed that the thing would last long enough for us to get the scene. After a few more takes, Steven yelled “cut” as the rain turned into a deluge. The landing craft turned to motor slowly back toward the beach. As I dug myself out from under the camo nets, I was doing everything in my power to hold back tears. It wasn’t the only time I have cried on a film set. But when I saw the scene in the theater, it’s some of the most exciting cinema I have ever witnessed—much less having been lucky enough to have been a part of. My point is that this work is always a place of intense concentration and attention. But it can be so very rewarding.

Finally, I did get a call to join the team for Fabelmans. And yes of course, I was available. It was exciting to be on a set with Steven again. The script was intimate and powerful, and it had a strong cast of people with whom I really wanted to work.

We all approach our projects in different ways. For me, the most important decision I get to make is in the selection of crew. Since the use of radio microphones has become ubiquitous, the utility sound position is as important as any other in the department. Of course, the personality and skill of the boom operator, the set-facing emissary of the department, continues to be of critical importance.

The crew we had on The Fabelmans was one of the best with whom I have ever worked. I was so lucky to have them. Boom Operator Michael Primmer’s skill and calm demeanor on the set was a delight and had a calming effect on our whole department. For the utility position, I always try to look for people who have worked a great deal in television, who have wired actors day-in and day-out for months at a time. Rebecca Chan was bulletproof. She was super organized and I admired her ability to walk on the set and make a wiring adjustment with an actor even when things were tense. She would be in and out before anyone could really notice or make an objection. We had Larry Commans a good bit as a Second Boom Operator. Larry is also a seasoned hand who has great ideas. Because of the small or constricted sets on the stages, Michael and Larry did a lot of work on the larger family scenes from high in the perms, so there was a lot of coordination with the Grip Department to lift ceilings. On these scenes, we would also use Rebecca on a Third Boom, or on a Second Boom when we didn’t have Larry.

In terms of gear and technique, my approach has always been to try to keep things as simple as I can. I have long been an admirer of Ed Tise’s rig and his tiny footprint, and I’m always looking to keep my gear as small and mobile as I can. I want to be as close to the set as possible—hopefully with a clear view of the proceedings. I know that I often annoy the Lighting and Grip Departments, who can’t quite gather why I am underfoot all the time. But as I said, for me the good stuff happens where the actors are performing and the more that I am aware of what is happening in that physical space, the better a contribution I can make—while maintaining communication with director, assistant director, and crew. I really do like to be part of the filmmaking process.

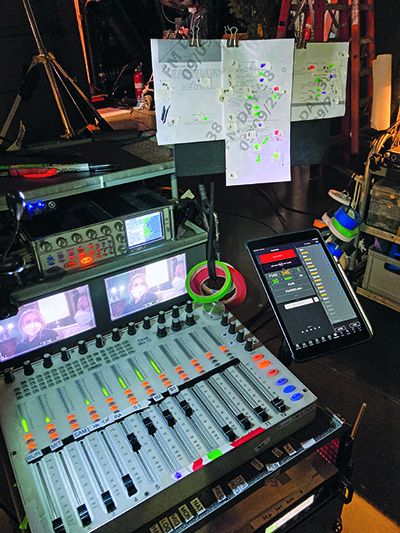

My primary recorder for some years has been a Zaxcom Fusion 12, paired with a Zaxcom Mix-12 control surface. For car rigs on Fabelmans, we used a Sound Devices 633 and 688 and I “mixed” on the front panels of these recorders. Finding a nimble and effective way to approach doing car rigs is an evolving and often frustrating art—especially these days with multiple last-minute schedule changes and limited prep time. For boom microphones, we generally used Sennheiser MKH 50’s. For radios, we used Lectrosonics DSQD and SRC receivers, with SMWB and SSM transmitters, along with DPA 6060 lavaliers. Over the years, I have gone through the whole gamut of lavaliers. I like the DPA’s, now that the build quality has become more robust. They take a lot more abuse than they did in the past. On Fabelmans, our radio challenges were not from crowded spectrum, but from the set itself. We did initially have a lot of issues with walkie-talkie interference with the DSQD receivers, which we more or less solved (by a lot of trial and error) with Wisycom-filtered antennas and an additional pair of RF filters right before the signal enters the receivers. There were multiple phone calls to the folks at Lectrosonics. It’s quite a task to try to work through some of these problems while on a production, but there’s generally no good way to duplicate the set RF environment for testing unless you are actually on a set. Before shooting, I visited the major locations and did radio scans to avoid bad surprises on shoot days, and this paid off well. The latest versions of the Lectrosonics Wireless Designer software are a lot more sophisticated in terms of frequency coordination. Most times, I start by letting the software choose frequencies, but then I will generally end by “hand picking” channels as well. I do need to mention that I understand that many crews are having good results with the Shure and other wireless systems, but up to now, I have stuck with Lectrosonics, mostly due to reliability, small size, and portability.

My biggest concerns regarding sound during this production were the numerous kitchen and dining room scenes with a large cast and wall-to-wall dialog. There was a lot of physical activity in these scenes—pots and pans, movement, food serving—a lot of it right over the dialog. I know that many of us have been in the position of wondering if and when to bring up these issues on a set, and anticipating that a director may understandably dismiss your concerns in the effort to capture a seamless and naturalistic performance from the actors. But the production mixer must always bring these things up. For some actors, the exact same qualities that make them so captivating as performers; their spontaneity and originality make them problematic for us in the Sound Department. Michael, Rebecca, and I were constantly on these sets trying to cushion the dinnerware, working to substitute wooden utensils instead of metal, being a general pain in the ass to the Prop Department. At times like these, it is good but hard for us to remember that the sound that we record is not an entity unto itself. Its only value is to be of service to the storytelling—to the narrative. To the extent that we, or any department, impose a condition on the filmmaking process, it is seen to be antithetical to the overall creative process. Thus, we are most often asked to fold our craft and technique into the larger process in such a way that to the casual observer, we are performing no obvious craft at all.

Having said all this, while prepping this article, I reached out to Gary Rydstrom (Sound Designer and Re-recording Mixer) and Brian Chumney (Supervising Sound Editor) to learn that there was very little ADR work done on any of these scenes. I was so relieved to hear this, but certainly can’t take all of the credit. We did the best work that we could in recording the original tracks, but I think the lack of ADR is as much due to the skill of the dialog editors and mixers for word or syllable substitutions from alternate takes when there was a crash or clunk over the dialog. As they say, it takes a village!

One of the big pleasures of the project for me was recording Mitzi’s (Michelle Williams) piano performances. I don’t often get the chance to record live music and I sometimes have a bit of a learning curve—which I really enjoy. We started the show with six or seven pre-recorded piano pieces. The word in the beginning was that the music scenes would all be shot to playback. But I knew from experience that we should also be prepared to record live. In the execution of the scenes, we recorded it all live. We would stay late the nights before and pre-wire the pianos and the rooms. Then while shooting the scenes, we would generally shoot the first take with a professional pianist hand double as a live record, and then use these recordings as playback for takes with Mitzi. In actuality, it would flip back-and-forth from take to take. The hand double might come back in for another live record, or it might be done to playback. Our department was pretty intensely focused to get the information as to what would be the protocol for the next take. But it went beautifully. Playback Operators Brandon Loulias and Jeff Zimmerman were always on their toes and always ready to go. As an aside regarding the music, prior to shooting there was some discussion among us in the department whether to record solely in Pro Tools or to double record the live-record music on a separate recorder at the same time. For safety, we made the decision to double record. We often had to push during the shooting to get complete recordings of the songs—knowing that complete versions could be crucial in post, and might help prevent our live recordings from being replaced. I was proud to learn later that a good deal of our piano recordings was actually used in the soundtrack.

I have worked long enough to see a lot of changes both in the way that movies are made and how film sound is recorded. There has been the evolution from film to digital cinema (and sometimes back), the advent of digital sound recording, multitrack sound recording on sets, radio mics, timecode, multiple cameras, performance capture, hybrid productions combining performance capture and live action, video walls, and much more. At the studio level, there is an ever-increasing concern about budgets, leading to less prep time and compressed shooting schedules. I feel that some of these developments (especially the use of multiple cameras and radio mics), along with stylistic changes in the aesthetics of film sound, have contributed to the finished dialog becoming somewhat less intelligible. Multiple times in the last few years, friends and acquaintances have asked me why they can’t understand the sound in movies anymore. My heart always sinks when I hear this. Many people turn on the English subtitles when viewing movies at home.

A lot of these changes have also hastened the relegation of the production sound mixer from being a kind of artist to the lesser status of technician. I expect that most readers of this article are sound professionals working in this industry, so you may be familiar with what I am writing about. Talking about this recently with one of my well-known production sound peers, he mentioned that in his opinion, it is the shooting of dramas that is the worst, because in these films, the dialog is everything—extremely important to the comprehension of the story, but despite this, the production sound team gets little consideration on the set. With due respect, my take on it is a bit different. I really prefer working on dramas, as I feel like that’s where I’m often able to do my best work—and dramas are in fact, the kinds of films that I most enjoy seeing.

And when starting to write this article, I reached out to Steven concerning his general take on The Fabelmans’ production sound, and in particular, the kitchen and family scenes I mentioned earlier.

I certainly appreciate his reply—

“Instead of causing problems, it enhanced a kind of naturalism of the kitchens we’ve all been in, as kids ourselves and with our own children, and made the scene feel as real as it possibly could feel… Ron has always focused on crystal clear dialog tracks. He has been responsible for allowing the actors to reach the hearts and souls, and minds of the audiences we make our films for… I’ve always felt that Ron and his department have been nothing but supporting of my work as a director, even when he has often come to me making me aware of the challenges that he is facing.”

I went to see The Fabelmans with my wife Jennifer and four other friends at a typical multiplex theater in Bozeman, Montana. It was a brisk day and we were all excited about spending the afternoon seeing the film on the big screen. I intentionally didn’t tell them anything about the production, as I didn’t want to in any way color their experience of it. Understand that these are some of my same friends who have asked me why they can’t grasp the dialog in films these days.

As for myself, I typically have an aversion to viewing a movie that I have worked on recently. The compression of three or four months of intense work into a two-hour movie can be overpowering. But watching The Fabelmans, for me was quite different. I was instantly transported into the realm of the narrative—a real tribute to the quality of this movie!

As we walked out of the theater, I huddled with my friends and before anyone could say anything, I quickly asked…

“Hey … could you understand what they were saying?”

“Yes, of course,” they all answered. “We heard everything!”

I would consider that a success.

Thanks to my fantastic crew: Michael Primmer, Rebecca Chan, and Larry Commans; Playback Operators Jeff Zimmerman and Brandon Loulias; to cooperative and supportive property and Costume Departments on the set; to Gary Rydstrom, Brian Chumney, Skywalker Sound, and above all, to Steven Spielberg … for both a career and for this unique opportunity.