by Scott D. Smith, CAS

This piece is a continuation of the article from the winter 2011 issue of the 695 Quarterly, which examined the early beginnings of Local 695. For those who toiled behind the scenes at the various studios during the mid-to-late 1930s, times were tumultuous. With the economy still reeling from the effects of the 1929 stock market crash, and unemployment in the double digits, Hollywood was not exempt from the crisis that gripped the rest of the nation. With much at stake for both workers and producers alike, a fierce (and bloody) battle ensued for the control of craft unions engaged in film production. In the end, the studios would be the ultimate winners, but there was no shortage of embarrassing moments for both sides.

While much ink has been spilled pertaining to charges of influence peddling during this period, I have tried to steer clear of any conjecture. Any opinions expressed herein are those of the author, and should not be construed as representative of the IATSE.

1935

Still reeling from the effects of the strike actions of 1933, Local 695 (and the IATSE West Coast locals in general) continued in their quest to negotiate a contract with producers. It was tough going. IBEW Local 40 continued to be a thorn in the side of 695, and they had lost a significant number of members to IBEW as a result. With membership dwindling and the possible extinction of the West Coast locals looming large, the International played the only card they had left—bring in the boys from Chicago.

The Chicago Connection

George E. Browne began his show business career in Chicago, having been elected in 1932 as the head of Stagehands Local 2. His assistant and right-hand man was one William “Willie” Bioff, who had an illustrious career as a small-time criminal, running prostitution and minor protection rackets in Chicago’s Levee district.

In the early 1930s, after hitting up a local theater chain for $20,000 in exchange for labor peace, Bioff and Browne went to a local club to celebrate their coup. It was during this drunken outing they had the misfortune of running into a gentleman by the name of Nick Circella, a member of Frank Nitti’s gang, who, along with Al Capone, controlled much of the Chicago mob during the Prohibition years. With the end of Prohibition in 1933 causing a severe dent in their cash flow, the Syndicate needed to come up with some creative ways to keep their empire afloat. The film business suited their needs perfectly. Bioff and Browne were subsequently invited to join the organization. The only acceptable answer was “yes.” Using his position as head of Local 2, Browne was able to exert control over local theater owners by threatening action by the projectionists.

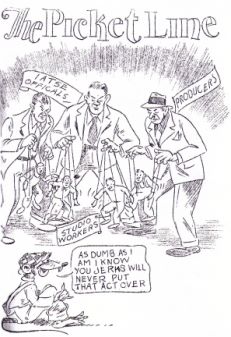

Industry cartoon from the 1930s. From The Story of the Hollywood Film Strike in Cartoons. Cartoons by Gene Price, book by Jack Kistner. From the collection of Dr. Andrea Siegel.

During this period, most of the major theater chains were still owned by the studios. In 1934, Browne, with the backing of the Chicago mob, ran in an uncontested election to head the International. Bioff, as his right-hand man, would accompany him to New York.

Having managed to seize control of the International, Bioff and Browne then went to the heads of Hollywood studios, threatening to disrupt the operations of studio-owned theaters unless they bowed to their demands.

Studio heads, having just lived through an expensive halt in production, were anxious to avoid any more labor problems. A previous, albeit brief, projectionists strike in Chicago had already cost the studios a significant amount of money and they didn’t relish the thought of further disruptions in either production or exhibition.

Studios Go Closed Shop Jan. 2

Thus read the headlines in the December 16, 1935, issue of Variety. After months of wrangling with the National Labor Relations Board and IBEW Local 40 over jurisdiction of soundmen, Local 695 and the International managed to regain representation of studio workers for most crafts.

This was a major coup on the part of the International, and brought at least 4,000 members back into the folds of the IATSE. While the tactics associated with this action would come back to haunt them, it did, at least for the time being, put the question of representation to rest. The move apparently caught many by surprise, including the cameramen, who just 10 days previously were still trying to sign members of camera Local 659 into the ASC guild.

However, the closed shop conditions did not remain in place very long. By April of 1939, the leaders of the International announced the return of an open shop policy on studio lots. This move was designed to head off a looming battle over charges that the IATSE was acting in collusion with producers to control labor rates and conditions.

1936—The Deal

In 1936, with the events the previous year still looming large in his mind, Joseph Schenck, head of 20th Century Fox, as well as the producers’ liaison for the Hollywood majors, was called to a meeting in New York with Willie Bioff and George Browne. At that meeting, Bioff declared that “I’m the boss—I elected Mr. Browne—and I want from the movie industry $2 million.” Schenck, astounded by the demand, began to protest, but Bioff warned him: “Stop this nonsense. It will cost you a lot more if you don’t do it.”

Two days later, at a second meeting, Bioff took him aside and confided: “Maybe $2 million is a little too much… I decided I’ll take a million.” In the end, Schenck agreed to pony up $50,000 a year from each of the majors and $25,000 from the smaller studios. Mr. Schenck later took a small bundle containing $50,000 in large bills to the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, dropped it on a bed, and looked out the window. Sidney R. Kent, president of Twentieth Century-Fox Film, came in and did likewise.

A year later, Schenck received another call from Bioff, and repeated the routine. This would continue until May of 1941, at which point Bioff and Browne were indicted and found guilty of extortion in federal court. They were subsequently given sentences of eight and ten years respectively, along with a fine of $20,000. Richard Walsh took over as President of the International. Joseph Schenck, for his part in the scandal, received a sentence of a year and a day, but received a Presidential pardon after serving four months. When faced with charges for his participation in the scandal, Nitti put two .32 caliber bullets in his head while standing in a suburban rail yard. Bioff, not long after his release, was blown up, along with his car, in the driveway of his home in Phoenix. Thus came to an end one of the most scandal-ridden periods in the history of the IATSE.

Local 695 Survives

While the actions of Bioff and Browne brought disgrace to the IATSE, the members of the individual locals continued in their fight for fair wages and working conditions. This effort on the part of the members would result in a new, more democratic IATSE Constitution. In addition, to their credit, some members spoke out against the rigged election of Browne as head of the International. For their trouble, they were frequently subject to beating by Bioff’s henchmen and “blacklisted” from working.

Tommy Malloy (no angel himself), who headed Projectionists Local 110 in Chicago, was one of those who had protested the influence of the mob during the wildcat projectionists strike of 1935. In response, his Packard, with him at the wheel, was riddled with machine-gun fire on Lake Shore Drive. The message was clear to both studio owners and union employees alike: go along with the program, or face the consequences.

With the issue of jurisdiction settled, at least for the time being, Local 695 went back to the task of organizing its membership, and signing up new members who worked in areas related to sound recording and reproduction. This included not only production sound and re-recording crews, but maintenance technicians and theater sound personnel, as well as those working at laboratory facilities.

One such group was the engineers and technicians who worked for ERPI (Electrical Research Products, Inc.), which was the engineering arm of Western Electric. Most of these men were part of the Western Electric engineering group which handled installation of sound equipment in studio facilities, and the installation and maintenance of theater sound equipment provided by Western Electric. Local 695 had previously signed many of the men who worked for RCA Photophone, and the signing of the ERPI engineers in June of 1936 further bolstered their ranks.

While these hard-won gains helped to establish Local 695 as the primary bargaining agent for production and re-recording soundmen, they would continue the fight for the representation of all soundmen working at theaters and laboratory facilities well into December of 1936.

1937

While Local 695 continued in its efforts to organize those working in sound-related crafts, the fight to maintain representation of soundmen was far from over. On April 30th of 1937, the Federation of Motion Picture Crafts (FMPC) staged a surprise walkout. The FMPC was essentially a coalition of unions under the leadership of Jeff Kibre and covered about 6,000 members in various crafts, including art directors, costume designers, lab engineers, technical directors, set designers, scenic artists, hair and makeup artists, painters, plasterers, cooks and plumbers.

Kibre was a second-generation studio worker. His mother, a divorcée who had moved from Philadelphia in 1908, worked in the art department of some of the studios. After studying English at UCLA, and failing in his bid to become a screenwriter, Kibre joined Local 37 and took a job as a prop maker. He was reportedly a likable man and had a talent for making those around him feel as though he understood their problems. He was also an avowed Marxist and Communist, but apparently did not follow the party line, preferring to make his own determinations as to the correct course of action. As such, the Communist Party leadership refused to support his actions, which left him on periphery when it came to organizing.

While the April 30th walkout against the studios eventually failed, Kibre was not totally out of the picture. With the help of attorney Carey McWilliams, Kibre reorganized under the banner of the IATSE Progressives, and began a campaign to investigate the mob ties of the International.

While Kibre’s efforts to clear the IATSE of mob influence may have been laudatory, his ties (however loose) to the Communist Party ultimately worked against him. To his credit, however, Kibre’s actions led to the resignation of Willie Bioff, and well as the end of the 2% assessment fee levied on all members of the IATSE by George Browne after he had been installed as head of the International.

In the end, Kibre’s attempt to organize various crafts failed amidst the continued allegations of Communist influence, which were picked up on and exploited by the media during the late ’30s and early ’40s. He also received numerous death threats during this period, to the extent that he required a personal bodyguard around the clock. Despite his failure at fully organizing studio workers, he did manage to negotiate a deal to leave town if the IATSE leadership agreed not to persecute the membership of the democratically oriented United Studio Technicians Guild. Upon his departure, Kibre went to work for the CIO fishermen’s union.

Unfortunately, the media attention surrounding Kibre’s Communist Party affiliation provided a further distraction for the studios to exploit, serving to deflect attention from their own role in influencing labor negotiations, as well as their mob ties. This unfortunate scenario played right into the hands of the producers, who were only too happy to instigate any unrest within the labor movement.

It was probably due in part to this unwarranted attention (along with Jeff Kibre’s continued actions against the IATSE) that the membership of Local 695 took the unprecedented position to vote against the autonomous local leadership during a meeting held on December 22, 1937. Apparently, members felt that they had a better chance of maintaining their current wage structure (paltry as it was), if they let the International handle bargaining with the producers.

It wasn’t until a contentious three-hour meeting, held nine months later on September 16th of 1938, that more than 400 members of Local 695 would finally nominate a new set of officers to the Local, thereby returning control to the officers and members (although the actual election was deferred until the 28th of the month). Likewise, three other key IA locals (Camera Local 659, Laboratory Technicians Local 683, and Studio Mechanics Local 37), also voted to return control of their unions to local leadership. Once again, Harold Smith was voted business representative for Local 695.

The question of certification of Local 695 as the exclusive bargaining agent for soundmen, which was initially filed with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) on October 12th of 1937, would continue to drag on into 1939, with no clear resolution.

Keeping Score—A Look at Wages

Given the current economic times we are living in, it is instructive to make a quick comparison of wages during the late 1930s. Below is an illustration of what a sound crew might expect to make on studio-based productions after new wage scales were put into effect in April of 1937, with equivalent comparisons to 2010.

Clearly, nobody was getting rich at these wages, especially when one takes into account that only very few of those members working in 1937 would be fortunate enough to work 42 weeks a year.

In comparison, it was reported in the September 17th issue of Variety that director Frank Capra received a salary of $100,000 each for three pictures, two bonuses of $50,000 each, plus 25% of the profits. While Capra was certainly an exception, director Rouben Mamoulian was reported to make $50,000 per picture, which is still nothing to sneer at.

Likewise, it is interesting to note that in September of 1938, Technicolor reported gross earnings for the first eight months of $862,612 (approximately $13.2M in 2010 dollars), which was nearly double the earnings for the same period in 1937. Somebody was making money—despite a national economy that was still faltering. (The national unemployment rate in 1937 stood at 14.3%, rising to 19.0% in 1938.)

It is therefore understandable when stories such as these hit the press, some crew members who toiled long hours in production might begin to feel that they were being taken advantage of. A similar parallel exists today when comparing the salaries of corporate CEOs to those of the workers who produce value for their companies.

1939 and Beyond

After having just approved the return to autonomous control of Local 695 by its newly elected board in September of 1938, the members would reverse this decision six months later. Fearful of losing the gains that had been made over the past years in wages and working conditions, the membership felt that the only leverage they had with studio management was the threat of a walkout by the projectionists.

Therefore, the members of 695 (along with Business Agent and International West Coast rep Harold Smith) felt letting the International handle the bargaining for a new Studio Basic Agreement would offer greater leverage than what they might be able to muster on their own. However, in a nod to local membership, it was agreed that any contract negotiated by the International would be ratified by the membership of the individual locals.

While the tactic of having the International control the negotiations may have been a good move in the short run (it took a threatened walkout of projectionists on April 16th of 1939 to even get producers to agree to come to the table), ultimately it placed a lot of power in the hands of the International, which at this time was still headed up by George Browne.

However, despite the events that would take place in federal court two years later, it is probably fair to say that Local 695, as well as most of the West Coast IATSE locals, would have not been able to survive the union-busting tactics of producers without having the projectionists support them. While some of the tactics employed by IA leaders during this period may be questionable, one must also remember that the studios employed their own set of “goon squads” which were equally unsavory in their tactics.

Ultimately, the greed of studio bosses was the factor that forced the rank-and-file membership of craft unions (regardless of their affiliation) to vote for measures that they might otherwise think twice about. Surely, most members of 695 would not have willingly handed over control of their local to the International unless they felt that was the only option left open to them.

While both the International and individual locals have to share some of the blame for the events that took place during this time period, if studio bosses had come to the bargaining table instead of trying to circumvent the rights of workers, things may have turned out differently.

© 2011 Scott D. Smith, CAS