Truth and Action

Sound mixes a moving palette for Spike Lee’s new joint

by Daron James

The Civil Rights movement in 1950s and 1960s America was a tinderbox ready to explode, then in the ’70s, it continued with the emergence of the Black Power movement. The latter is the historic setting for BlacKkKlansman, a taught sociopolitical film from director Spike Lee.

Based on the book Black Klansman by Ron Stallworth, the first African-American detective in the Colorado Springs Police Department, the adapted screenplay follows the true story of Stallworth’s (John David Washington) infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan and his eventual take down of an extremist hate group.

Production Sound Mixer Drew Kunin, Boom Operator Mark Goodermote, and Utility Marsha Smith took on the project, a paced schedule lasting from October to December 2017 that included a glut of filming locations in New York and a jaunt VFX stop in Colorado to blend Centennial State exteriors into the Big Apple.

The movie opens up in black-and-white, featuring Alec Baldwin as a bigot-spewing racist; a 16mm projector beams images of his message overlapping his face and onto the wall behind him—the noise of the machine pierces through the soundscape. On set, everything was done live with no visual effects. It meant the clacking of the projector would compete with Baldwin’s dialog. “I didn’t know how loud Alec was going to be, which turned out to be very,” says Kunin. “I was a bit surprised when he launched into it—it was a little bit of wild ride to keep his level from overloading, but we were lucky he had enough volume that overrode the projector.” Sound ran a Schoeps CMIT-5U as boom and placed a lav for dialog.

Kunin uses a mix of DPA, Sanken, and Countryman lavs with Lectrosonics wireless on projects. His general mantra being to only wire when necessary, however, on BlacKkKlansman, they went ahead and wired everyone to be safe. Multiple roaming cameras shooting wide and tight coverage were an acting catalyst, but also being the team’s first project with Lee, they didn’t want to interrupt the rhythm with the need of adding a lav after the fact.

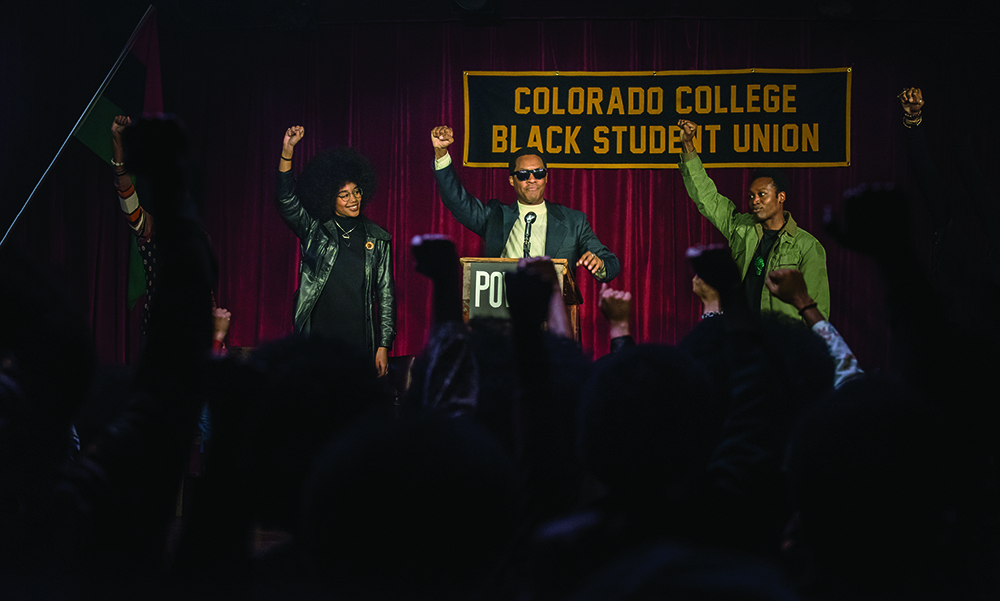

We first meet Stallworth working in the file room of the police department but he soon receives his first undercover assignment to attend a lecture delivered by Black Panther Party philosopher Kwame Ture aka Stokely Carmichael (Corey Hawkins). It’s here he meets Patrice (Laura Harrier), a fiery activist Stallworth warms to. Inside the assembly hall, hundreds of extras look on, shouting with praised remarks during Ture’s moving speech.

Sound couldn’t place a microphone overhead Ture because of wide camera shots. Instead, the period microphone at the lectern was made live and an additional plant mic was hidden. Another boom captured reactions of the crowd.

For that scene in post, Re-recording Mixer Tom Fleischman, a longtime collaborator of Lee’s, augmented the speech with a bit a reverb to add to the size of the room and layered dozens of responses from the crowd. “Drew turned in production tracks that were really well recorded. When you have a good track, it makes my job easier,” says Fleischman.

The challenge of the Ture speech scene in post was making sure the audience callouts felt like there were actually in the room and not ADR. Mixing in 7.1 made it easier for Fleischman, then it became a matter of going through it to make it sound natural.

“It could have easily become quite a noisy scene, but my philosophy at any given moment in any film is that there is one sound that needs to be in the forefront,” says Fleischman. “We needed to balance the scene in a way that made sure every line was intelligible so that the underlying track sounded real to the audience and not like they were hearing something in a vacuum. The whole idea for me is story and keeping the audience involved and not letting them be distracted by any sound element.”

If you listen closely to the scene, you will hear a “boom shakalaka” from the crowd. That’s actually Lee’s voice. During the mix, the director asked Fleischman to grab a mic so he could record the audio and found spots for it in the scene.

After that initial assignment, Stallworth starts his own undercover operation after stumbling across a newspaper ad from the Ku Klux Klan seeking new members. Stallworth calls the number on the notice and David Duke (Topher Grace), the leader of the hate group, actually picks up the line. Disguising his voice, Duke thinks Stallworth is a racist white man and invites him in the inner circle.

To shoot these scenes, Production Designer Curt Beech built two sets outfitted with period-appropriate props on NY stages so production could shoot Stallworth and Duke simultaneously. Sound recorded both actors’ dialog simultaneously as well. “We placed mics overhead on both ends, plus we tapped the telephone line on a separate track for editorial to play with,” says Kunin, whose cart setup is based around a Sonosax mixer and an Aaton Cantar X-3 recorder. All Fleischman had to do was “filter down the track a little” to make it sound more like it was coming from a phone.

Stallworth, now a member of the KKK, has one problem: he’s black. To be the face of the operation, he asks fellow detective Flip (Adam Driver) to pose as Ron, where he meets the leader of the local chapter, Walter (Ryan Eggold). Stallworth asks Flip to wear a wire and Kunin was able to find a few in the style of the old BCM 30 to put on camera, which added to the complexity of lav placement.

Costumes from designer Marci Rodgers posed a different challenge as they lauded the fashion of the time. Stallworth wore lush colors, jazzy prints, and mixed textures of denim, velvet shirts, silky button-downs, suede vests, and leather jackets. To lav Washington, center chest became the default position to avoid material movement leaking into the track.

For Patrice, she was dressed in long leather jackets, dark turtlenecks, mini-dresses, and knee-high boots, among others. “Laura was a little tricky to mic,” admits Kunin. “Not because of the material she was wearing but because it was hard to hide a mic. Marsha worked with wardrobe to sew in special compartment to place in the bodypacks.”

Sound had to pay close attention during the nightclub scenes Ron and Patrice go to hang, talk, and dance. For dialog to be mixed cleanly, Kunin dropped the song to capture the dialog and used a thumper to aid the beat. Music is a big part of Lee’s storytelling. Besides the musical soundtrack that includes “Too Late to Turn Back Now” by Eddie Cornelius and “Oh Happy Day” by Edwin Hawkins, the director tapped Terence Blanchard (Malcom X, 25th Hour) for its score.

“When it comes to writing music, I let the film tell the story,” says Blanchard. “The first thing I thought about when I saw a cut was Jimi Hendrix playing the National Anthem on guitar. Being an African-American, you’re constantly bombarded with issue of bigotry every day. This story is a reaffirmation of what we’re going though. Jimi was a primal scream for all of us, so it’s why the electric guitar plays a prominent role in the sound of the score.”

Flip, now deep in the local Klan chapter, attends meetings at the home of Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen), a follower who wants to put words into action. It’s here the undercover detectives learn Felix is planning a plot to spoil another activists meeting; one that involves a character played by Harry Belafonte, an icon of the Civil Rights movement.

Felix’s residence, a practical location found upstate in Ossining, New York, was small and scenes were filled with multiple actors and multiple cameras. At times, squeezing in a boom operator was not possible, especially when Felix puts Flip through a lie detector test in a broom closet of a room. It meant sound had to rely on plant mics and lavs to cover the dialog. In other tight locations, gaps in the wall allowed to place the boom in the room but not Goodermote.

Leading up to the climax of the movie, picture intercuts two different story plots. On one side, you have Flip being initiated into the Ku Klux Klan, where a crowd gleefully cheers during a screening of 1915’s The Birth of a Nation. On the other, a group from Patrice’s African-American student union peacefully sits around Belafonte as he delivers the most galvanizing moment in the movie; a recounting of the lynching of Jesse Washington he witnessed as a young man. “To see him was a very powerful moment,” says Kunin. “Working on that scene had so much gravity to it, we took extra precaution in our approach.” In recording Belafonte’s dialog, sound let the cameras set up its shots, then they strategically placed an extra in front of a plant mic for additional recording.

Though backdropped in the mid-’70s, the film is not only about the past but about the state of how we’re living today. Nothing couldn’t be more evident than the film’s final sequence; a collection of uncensored videos from the Charlottesville protests. Lee left the material untouched. “What you hear is the sound straight out of the smartphones and online videos. There’s no foley or effects added,” says Fleischman. “We only mixed in the score and it plays against the raw sound really strongly.” Blanchard notes, “That’s classic Spike. He makes a statement about what’s going on in our country and leaves you there to think about it.”