by Simon Hayes AMPS CAS

The first part of Simon’s article appeared early this year when No Time to Die was originally scheduled to be released in the spring. But like everything COVID, the release date has been pushed to October. –Editors

Jamaica, our next location, presented new challenges. We had a lot of vehicle dialog to record, including one scene with Bond on the back of a scooter. Cary Fukunaga favours realism and it was no surprise when I learned he wanted to shoot the dialog with the scooter being self-ridden, rather than being pulled on an A frame or on a low loader (flatbed). We always placed a lavalier on the exhaust of the scooter so the sound post team could give Cary options in the final mix on how loud he wanted the engine to be under the dialog. With the actors’ radio mics, it was a case of getting the lavs as close to their mouths as possible to try and increase the signal (dialog) to noise (scooter engine). We rigged the lavs far higher on the chest than we normally would. We try to keep the dialog sounding natural, and our usual placement would simply mean any quiet words, or times when the engine was revved harder, would have drowned out the dialog, so all bets were off, and we just aimed to record the dialog absolutely as close as possible.

We also had to mic up Bond’s open-top Land Rover. As well as mic’ing the engine and exhaust as previously discussed (stereo lavs), we also had to capture his dialog. We did our usual workflow of rigging a Schoeps CMC6/MK41 capsule, using an active Colette cable to allow the capsule to be rigged remotely in the sun visor, as close to Bond’s mouth as possible. Unless the vehicle wasn’t moving, this placement wasn’t too successful. The exterior background and engine noise were just too loud to get what I considered to be rich, up-front dialog. So, once again, the DPA 6061 was my favourite choice in this scenario. The beauty of having twenty-four tracks was that I didn’t have to decide on the set; I could record all the elements and choices on the ISO tracks and making clear notes on the sound reports of what my preferred tracks were and what the components of the mix track were, giving the Dialog Editor a heads-up, and a starting point.

We also had scenarios where Bond would drive into shot, come to a halt and talk to someone on the sidewalk or in another vehicle. We could now swing in the booms with Schoeps Super CMIT’s due to the Land Rover having an open top, and capture the static dialog, creating another choice for post.

I had been looking forward to a nightclub scene in Jamaica. Cary said it was going to be a very high-energy, dancehall-type scene where the music would be loud and there would be a large number of dancers. Usually on these types of scenes, I use earwigs (wireless inductive earpieces) as my ‘go-to,’ but as we had no lip sync to worry about, and the set would be very dark and the dancing extremely energetic, I was concerned the generic earwigs we carry (i.e., not bespoke custom fitted to the individual ear canal) would potentially fall out of dancers’ ears and get lost, slowing the shoot down and costing production. I decided to go old school with our large JBL PA rig, including a high-power subwoofer, and about 15kW at our disposal. I asked Cary if he was cool with me using a thumper track. Cary was really excited about this, as he felt keeping the sub bass going during the six pages of dialog at a table on the edge of the dance floor would really help to keep the energy up, not just amongst the dancers but also from the actors. We have all been in situations where we are recording a nightclub scene and the actors start the scene talking loudly above the music, but as the scene progresses, their dialog levels slowly reduce, as they feel quite exposed speaking very loudly when there is no music in the background during the shooting. The beauty of using the thumper track is that it can be played loudly throughout the scene without being recorded by the microphones, and if there is any low frequency spill picked up, it can easily be filtered out in post. I chose 35Hz to create the thumper, as I feel that is low enough not to have any harmonics that will interfere with the dialog on the mics, but high enough that everyone in the club can hear it.

aniel Craig) and Moneypenny (Naomie Harris)

Robin picking up the car door slam and Arthur waiting curbside for the dialog; Daniel Craig

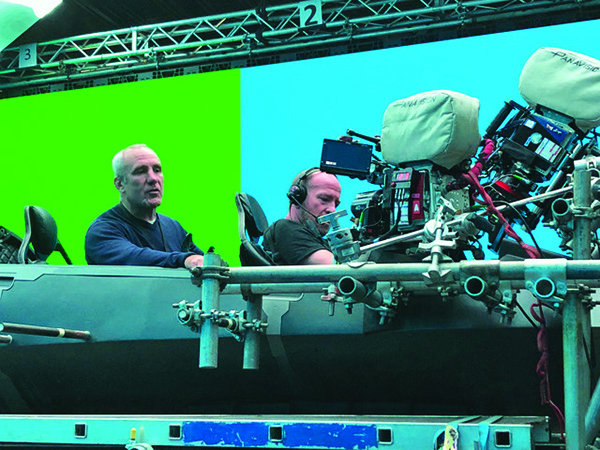

Simon Hayes checking the Schoeps MK41 placement on the plane rig.

A really important point regarding the scene was Daniel Craig’s support of this workflow. On Layer Cake, more than a decade earlier, after much discussion with the director and Daniel, we used a thumper track on a nightclub scene with excellent results. The actors kept their level up throughout, allowing the Re-recording Mixer and Director to really push the music cues in the mix without having to pull down the music for the dialog which, in my opinion, always sounds a bit wrong and weird. Daniel remembered that and was fully supportive of my decision to use a thumper again. On the rehearsals, he asked that we play the music tracks full range through the JBL’s, so he and the rest of the cast could find their level Cary had chosen these, and they were extremely bass-heavy dancehall-style tracks. I suggested to Cary, Daniel, and Jon the 1st AD that as soon as Jon called, “Standby!” I would start playing the music very loud, full range through the PA, while Jon got the sound and cameras rolling, and leave the music playing during the clapper boards. We were shooting two cameras then on the “A” of “ACTION!” I would drop anything above 35Hz and just continue with the thumper. This really helped the cast keep fresh in their mind how loud the music would be in the club and the vocal level they would use. As I was recording the dialog, I knew it sounded completely real and that Paul, the Re-recording Mixer, and Cary would really be able to go to town with the Dolby Atmos mix. Keeping the music level high without the fear of swamping the really important plot line dialog.

Cary and Linus’s decision to shoot with the same lens sizes on both cameras meant that we could get the booms in nice and tight onto the edges of frame without being pushed wide due to a ‘wide and tight’ scenario. Cary would now allow the actors to overlap when they felt the script would benefit from it.

Shooting cross mid-shots and then cross close-ups, always keeping everyone at the table in shot regardless of where they were sitting, gave Cary the ability to use direct action cuts on the overlaps. He spoke to me about this strategy and I wholeheartedly supported it. I always want to help and encourage anything that makes the performances more believable, and the scene really benefitted from the overlaps, bringing about an energy that can be difficult to find again in the edit. What was fantastic by keeping the lens sizes the same, was Cary and Linus knowing exactly how to make this work for the production sound. This enabled me to prioritise the booms and record really rich dialog. Although the nightclub was an interior, I decided to employ the Super CMIT’s, as they would be helpful at reducing the footfall from the dancers (I also had our 2nd AS, Ben Jeffes, removing the shoes of any dancers whose feet were not in shot), but I also knew the Super CMIT’s would be great at reducing, if not removing, the 35Hz thumper track. One of the issues of using a thumper is that sometimes the sub bass can rattle the set, or the glasses on the shelves behind the bar if they are touching, so there is a certain amount of audition time, playing the thumper before the shoot begins, and walking around to find rattles and reduce them. This can be by simply removing offending items, getting a standby carpenter to nail stuff down, or working with the set dresser to adjust any set dressing that is noisy. Once this is achieved, it is a good idea to use a volume that is loud, but just below the threshold that will rattle what is left, as the rattles could well be within the dialog frequencies and won’t be as easy to remove. I also put a very gentle slope 90Hz low-frequency cut onto the mix track. This is something I rarely do—I usually record completely flat with no bass cut, unless we have wind on the mics on an exterior, but I felt it was helpful to gently reduce the thump from the dailies and I knew 90Hz would not negatively affect the dialog.

Lashana Lynch (right).

We used three booms, all of them with Super CMIT’s, as there were some very hard spotlights and mirrors in the club. We all felt that employing three booms would reduce the likelihood of shadows or mics in the mirrors, and reduce the swinging by placing a boom on each character. The scene worked really well and when I phoned Picture Editorial the next day to ask how much of the thumper they were hearing in the Avid, they said, “What thumper?” When I explained what we’d done, the 1st Assistant Editor couldn’t believe he couldn’t hear it and told me he would go into the ISO tracks and have a listen, as they had only been using my mix. When I called back, he let me know that on his studio monitors he could not hear the thumper on any of the booms or the lavs. This was really great news!

filming in 35mm.

Our next location was the beautiful city of Matera, Italy. Constructed in 10 BC, it resembles a city in the Middle East. It is one of the oldest cities in Europe with its original architecture still intact. This location brought its own share of physical issues due to the restrictions on vehicular access, which meant carrying the sound cart and ancillary equipment up and down thousands of stairs per day. It was extremely physically demanding. For this work, we reduced the weight of my usual Eurocart, which is based around an alloy-tubed Ursta cart, which UK readers will be familiar with. We already run a very light 100Ah lithium battery on it, but for Matera, we removed anything that was not strictly necessary. We probably reduced its weight by around 10kg (25 pounds). I don’t like working in a bag for a lot of reasons; mainly the difficulty in watching three or more cameras without my usual monitors, and the compromises regarding radio and comms reception. I will go handheld in extreme circumstances, but for Matera, we decided to build an extremely lightweight cart for situations where we wanted to have access to all of our radio mics, sound crew comms, and picture monitoring, but in a location where it was impossible to carry our 80kg Eurocart. Our lightweight cart was the Cannibal Industries/Tone Mesa “Super Zuca” cart. These are great little Zuca carts, expertly modified for our industry to add some extra strength where required whilst still retaining the extremely lightweight and small footprint of the Zuca. I basically mirrored the equipment and capabilities of my main cart, but without the large 12-channel Audio Developments mixer board that I like to use. The Super Zuca housed a Zaxcom Deva 16, a Sound Devices 688 (for safety copy and additional output routing), a Lectrosonics Venue field receiver, along with a slightly simplified version of our Sennheiser RX/TX array for sound crew comms. This tiny cart was powerful, but could be carried up multiple staircases by one person. It also had the ability to become a true “bag” in a matter of seconds, simply by detaching from the cart and switching the power source. This was especially useful for interior car shots, or any ridiculously difficult locations that needed accessing.

Our main Eurocart, once it had been on its ‘diet,’ was fairly easy to get into places so we only used the Super Zuca about three or four times while we were in Matera. When we did need the Zuca, it was invaluable and did its job adeptly and elegantly. The only compromise I had to make was mixing without Penny and Giles sliding faders!

The vast majority of our work in Matera were action sequences, generally involving vehicles.

Cary and his stunt team worked with the mantra of ‘keeping it real’ on the stunt and driving sequences. If Bond and his passenger had key dialog in a vehicle as it was being driven at speed, Cary still wanted to capture it, rather than putting the car on a low loader, limiting the speed the vehicle could travel and, consequently, the energy that real driving brings to the screen. A long time ago, I decided when faced with this kind of scenario, rather than try to keep within radio range in a follow vehicle, which is notoriously difficult to trust with so many elements that could conspire to leave us too far away. My strategy would be to use the huge dynamic range digital recording affords us by placing a bag in the trunk of the hero vehicle, strap it in, set reasonable levels based on my knowledge of what the vocal performances will entail, and leave the recorder running without me directly monitoring as we shoot. This means I am less able to supply an elegant mix for Picture Editorial, instead simply opening up the actors’ mics onto the mix track. The positive is, in my opinion, that sound post and the final movie will get better production dialog as the antennas and receivers are inside the vehicle with the actors, so range is perfect throughout. It also allows me to hardwire the Schoeps CMC6/MK41, so I am delivering a lav and a hardwired hyper-cardioid on each actor (the latter generally rigged in the header or the sun visor, depending on the shot).

When using this methodology, I have some limiters set up at the higher end of the dynamic range, so if there is a sudden scream or a shout, the limiters save the recording from square wave or digital overload. In the same token, I make sure I am using enough gain and set the mics close enough that if an actor reduces their level to a whisper, I still capture that and, though it may be at -40dBFS or -50dBFS, it can be boosted by the Dialog Editor without increasing electronic noise/hiss. For me, this is the safest way of delivering high-quality dialog in this kind of extreme circumstance, rather than trusting radio range and working from my cart in a follow vehicle. Although I can’t deliver a more crafted mix track, I know the Dialog Editor will remix the ISO’s in Pro Tools anyway.

I still ride in a follow vehicle, monitoring a Sennheiser EW pack (the UK version of a Comtek), so I can get a feel for the performance and hear if something disastrous happens, like a lav falling off an actor or a battery mysteriously running out. That way, each time we stop at the end of the ‘travel,’ I can get out, access the sound bag in the trunk, and fine-tune the ISO track gain levels based on the performances I am listening to. If necessary, I can also adjust the input gain settings on the actors’ Lectrosonics transmitters with the app.

On these types of days, I would recognize the fact that my crew would probably have some downtime and sent our 2nd AS, Ben, out to capture stereo atmosphere tracks of interesting sounds unique to the location. This was something Cary specifically asked for, as he prefers using real ambience, feeling there is a truth within them, rather than synthetic or ‘built’ atmospheres. He likes to use a real atmosphere ‘bed’ for his sound designers to then build layers. At each location, at those times where I did not require my full crew, Ben would go off to harvest interesting sounds in M&S stereo, using my Neumann 191 mic. Oliver Tarney had asked that these tracks be delivered in M&S so he could decide later whether mono or stereo was appropriate, depending on the finished scene, the rest of the sound design, and the exact ambience he was using.

When we arrived back in the UK, our work was mainly on interior studio sets. There were a lot of important storytelling scenes taking place in the MI6 offices, including M’s office. I have always loved these scenes in Bond movies, feeling they provide a quintessential British charm, in which Bond’s colleagues are usually relaxed, unruffled, and professional, despite the frenetic and energetic action sequences of the story they are often intercut with. I really wanted to use sound to help support this. I decided that all of the MI6 scenes were an excellent opportunity to let the dialog breathe by prioritising camera perspective. I knew that much of Bond 25 would require the Re-recording Mixer to use the close-up mic perspective choices on most scenes, to allow the score and sound effects volume to be raised. Whether the final choice was to be boom or lav was immaterial, it would be whichever sounded closer and richer. On the contrary, I felt it probable, based on the script and the way Bond films usually sound, that when we cut to the MI6 offices, the score would probably be lower in level and the sound effects sparse. It was an ideal opportunity to prioritise and celebrate camera perspective. We did this with three cabled booms on everything. At all times, we had the three boom poles cabled up and ready to go, with Ben Jeffes available to jump on to the third boom, joining Arthur Fenn and Robin Johnson whenever necessary.

We used my all-time favourite film dialog capsule on the booms—the beautiful Schoeps MK41 hyper-cardioids, which I have always felt sound completely natural whether in close or wide positions. I had also just been sent some new prototype preamps by Schoeps to evaluate. They were the CMC1, a miniature version of the classic CMC6. There is no compromise: The CMC1 sounds just as good as the CMC6, and on paper are actually slightly better due to the modern circuitry within them. To my ears, they sounded exactly the same, but were smaller and lighter; a ‘win-win’!

As far as ‘prioritising’ the camera perspective, I was still using DPA lavaliers and Lectrosonics transmitters on all the actors. However, I decided to never fade them into the mix track on these scenes. They were there as a fallback in case the Picture Editorial team or Oliver were presented with circumstances that really required close-up dialog on a mid or wide shot. I wanted to create a confidence and familiarity within the Avid cut for Cary and the Picture Editors that would promote the sound I was trying to deliver on the MI6 scenes; an old school fully boomed sound that matched the camera angles. We were able to use cables on all scenes apart from one Steadicam walk and talk through multiple offices. Cabled booms are always my priority, and aside from an ‘on-mic’ bass cut of 60Hz between capsule and preamp to reduce infrasonic disturbances from any boom handling, all of the MI6 dialog was recorded without any EQ to really deliver the rich dialog I was trying so hard to achieve.

Worthy of mention was another big scene we shot on the sound stage in the UK was a huge black tie event that Bond and actress Ana de Armas were attending. In this scene, both actors are able to talk to each other at a distance in whispers, via hidden comms, as they make their way separately through the party in constant covert communication. A lot of this scene would be covered by two cameras in real time, one camera on Bond and the other on Ana’s character as they navigated their solo routes talking to each other. This gave Cary the ability to use direct action cuts, but it also meant we couldn’t cheat the comms, they had to be real and reliable. We used our tried and tested ‘musical’ system of huge induction loops around the set, with Daniel and Ana fitted with bespoke earwigs that would be invisible on camera, unless Cary wanted them to be seen. The earwigs looked exactly the same as the items a real Secret Service agent would be using. I fed Daniel’s lavalier into Ana’s earwig and Ana’s lavalier into Daniel’s earwig, using auxiliary outputs on my Audio Developments AD149 mixer. This gave them the ability to communicate covertly and discreetly with each other in separate rooms exactly the same way two real agents would. It was a complex scene, and had we not have been able to deliver this audio solution, it would have compromised the approach Cary and Linus wanted to use with the cameras. I am very happy it all worked so smoothly.

One of the rarer sound workflows we used on No Time to Die was the VFX paint out. It was a big scene with Rami Malek shot in a huge, beautifully designed set with very hard lights, precluding the use of booms. It was a performance-driven scene with pages of narrative as Rami encountered different characters. Cary chose to shoot on three cameras with two of them using very long lenses to get in close, but the third camera shooting extremely wide to capture the architecture of the set in all its splendour. After a rehearsal, I knew that Rami’s costume was not going to allow us to get usable production dialog with a lavalier regardless where we placed it. Our booms could never get close, and even if we busted the wide shot, the booms would create shadows on the closer angles. I didn’t have much time before shooting, so I quickly called Arthur over and asked him to go and talk to Rami and his hairdresser and ask if we could place the lav in his hair. Arthur was, of course, concerned that we would see a cable running down Rami’s neck to the pack and I said, “leave that to me.” I immediately went to our VFX Supervisor and explained the issue. I told him that I’d watched the rehearsals and the chance of us ever seeing the back of Rami’s neck in the final cut was low, but if we did, could he agree to painting out the lav cable. The VFX Supervisor was extremely quick to agree to this at the last moment when time really was of the essence. All it took was for me to explain that his decision could potentially stop Rami and Cary having to ADR the whole scene. I think I was also helped by the fact this was the only time I asked for a paint out in the film. I went over to Arthur, Rami, and the hairdresser, who were in the middle of rigging the mic assuring all of them that VFX had given the all clear, reducing the concern (especially from the hairdresser). I then went to see Cary and Jon, the 1st AD, and explained that if they caught a wire on the back of Rami’s neck, not to be concerned because VFX were kindly going to remove it in post.

One of the great things about working with Cary was his ability to take in information like this and trust his crew. He was aware that the booms couldn’t get in close enough and he asked me, “will this mean no ADR,” which I replied, “yes,” and he immediately said, “that’s fine.” I usually like to have everything planned and agreed to in advance, especially when it comes to painting out lavs or booms but in this instance, it would have been impossible to plan ahead. Cary’s ability to support me instantly was incredibly motivating. The scene ended up sounding absolutely fantastic with Rami delivering lines captured by a close DPA 4061 right at the front of his hairline, expertly hidden by his hairdresser. This is exactly the kind of collaboration that was present between all departments through the entire shoot.

On reflection, shooting a Bond movie was indeed everything I hoped it would be. The crew were always treated by the production as if we were all collaborating at the highest level of filmmaking. This atmosphere was promoted by Producers Barbara Broccoli, Michael G. Wilson, Gregg Wilson, Chris Brigham, and Chris Brock. I cannot begin to explain just how much effort Barbara Broccoli puts into the minutiae of every detail. It honestly feels like you’re working on an intimate, independent project, where everyone’s opinion is valued and each crew member, from the HOD’s to the set PA’s, are treated with the utmost respect and supported throughout. I had often heard this was the case, but to actually experience it was something I will treasure for the rest of my career.

I’d like to thank my sound crew for their on-going collaboration, professionalism, and skill:

Main Unit

Key 1st AS: Arthur Fenn

1st AS: Robin Johnson

2nd AS: Ben Jeffes

Trainee: Millie Akerman-Blankley

Second Unit

Sound Mixer: Tom Barrow

1st AS: Loveday Harding

3rd AS: Francesca Renda

Splinter Unit

Sound Mixer: Alan Hill

1st AS: Jackson Milliken

Main Unit Equipment

Zaxcom Deva 24

Sound Devices 688

Audio Limited 149 bespoke 12-channel mixer with AES outputs

Schoeps boom mics: CMC1 MK41 & Super CMIT’s

DPA lavaliers

Zaxcom & Lectrosonics radios TX & RX

Sennheiser EW comms