Bruce Bisenz: His Personal Best

by David Waelder

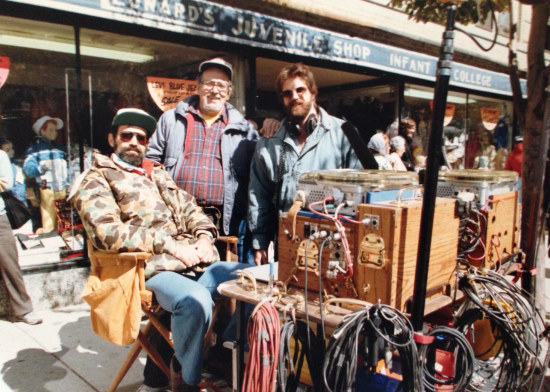

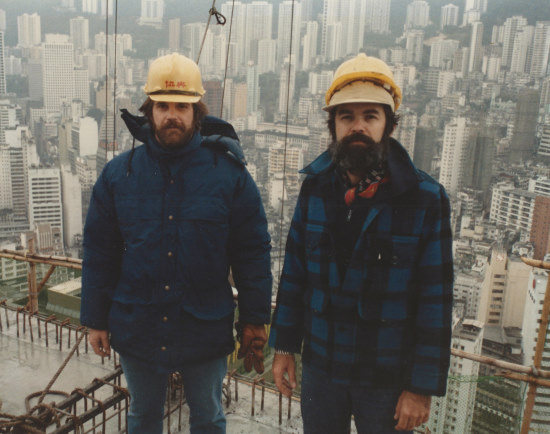

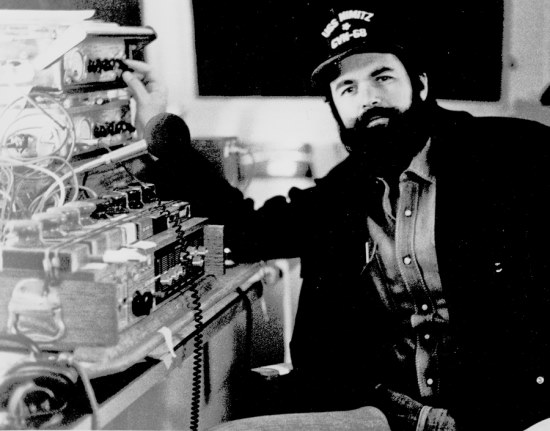

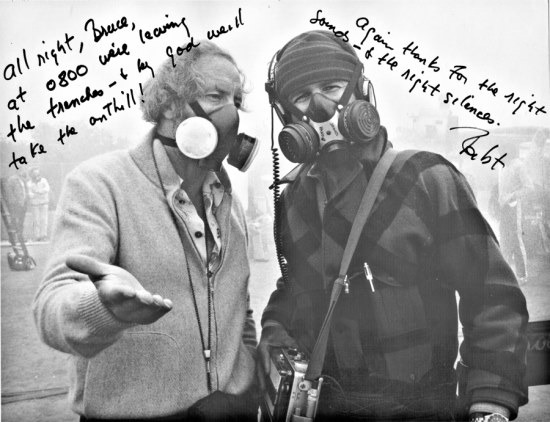

Photos courtesy of Bruce Bisenz

Robert Towne: (recalling an interview prior to hiring him for Personal Best) What got me about Bruce— he did a movie about horse racing and I remember asking him about how he set up the sound on that movie. He told me there was nothing that he had seen or heard [in other horse racing films] that was unique in the way he figured it should be. He went out and recorded sound out on the track of the jockeys in the middle of a race and he said he’d never heard anything like it. It involved the way that the jockeys spoke and how significant [that] was and he described to me the ways in which it was different. I was fascinated because I felt that that’s the sort of thing that I wanted to do with track and field.

Jeff Wexler, CAS: I consider him somewhat of a mentor to me because anytime I was having any difficulty or I was, wanted to build something or had to do a job that I didn’t really understand completely, I would always ask Bruce, well, how would you do this … and Bruce always had an answer. It often was not the answer that I would get from any other Sound Mixer …

Bruce Bisenz has a well-earned reputation as a technical wizard. He designed and built much of the equipment he used throughout his career and he personally performed bias and alignment calibration (not a simple task) for all his recorders. It is particularly remarkable that he is essentially self-taught with little or no formal training in electronics or sound recording practices.

Coming out of military service in 1967, he was unsure what to do next but he had a good friend in David Ronne, who had already established a career in production sound. Bruce had an interest in hi-fi and work as an electronics technician, so David encouraged him to apply to FilmFair where he, until recently, had been working as George Alch’s assistant.

He stayed with FilmFair about two years, replacing David as George Alch’s assistant. He learned everything he could about production sound recording from George and then moved up when George left. He was also involved in Post Production, making transfers and preparing tracks for mixing, an experience that helped develop a sense of what was needed and what worked on screen.

Although he was earning good money at FilmFair, Bruce only stayed another year and left to tour Europe for a network miniseries hosted by skier Jean-Claude Killy. Returning home, he found work on documentaries and corporate projects. His friend David Ronne was then heading the Sound Department for Wolper Productions and recommended him for assignments including a special with historians Will and Ariel Durant and documentaries with Jacques Cousteau.

David Ronne introduced him to the practice of working with a handheld Nagra and a shotgun microphone, starting with a Nagra III and an EV 642 and progressing quickly to a Nagra 4.2 and the Sennheiser 804. That combination was a game-changer at the time.

A recordist, working alone, could produce a quality track that had previously required several people and a truck full of equipment. It was also an excellent training ground; the immediacy of working directly with the recorder and a handheld microphone imparts a keen sense of how microphone position determines the sound.

During this period and his time at FilmFair, he read everything he could find about sound recording and the science behind it, making a vigorous effort to understand all of the factors that determined the characteristics of a recording. This practice of total immersion investigation became a life habit. Portable radio transmitter/receiver sets were becoming more reliable so Bruce wanted to make the lavalier microphones used with them sound more natural. Over time he determined the placement and EQ that would allow him to ‘Mix and Match’ with his fishpole microphones. This was especially important in the days of singletrack dialog recording (no pre-fade backup tracks) when all microphones were mixed together.

Portable mixing panels with full parametric EQ were not available at that time, but David Ronne was building a device with potential. Ronne took out the guts of a Nagra and coupled a microphone preamp to a line preamp and bundled them together in a separate enclosure. Using this outboard preamp allowed feeding a third microphone to the two-input Nagra (or more if one daisy-chained the devices) and several Production Mixers built similar interfaces. (See the profile of Courtney Goodin in the Summer 2011 issue of the 695 Quarterly.) Bruce Bisenz took the design a bit further.

He recognized that the Nagra line output card was sufficiently hot to drive a passive Program or Graphic equalizer and still yield an output that could be recorded through the Nagra line input.

Bruce collaborated with his engineer friend, Paul Bennett, to custom-build a microphone mixer using Nagra cards with Bennett-modified Altec Program and Graphic EQs configured with the curve that Bruce specified to make radio microphones sound natural. They also fit custom 24 dB/octave high-pass and 18 dB/ octave low-pass filters. They even hand-selected capacitors and other components. The capability of this mixer-equalizer coupled with his experiments in microphone placement gave him the tools to tackle nearly any recording challenge.

Television commercials and documentaries were the sole beneficiaries of these skills for a long time but a change in advertising practice nudged Bruce to change direction in his career. He had been happy working commercials but the change from sixty-second to thirty-second spots diminished the work days needed on commercials and encouraged him to seek out long-form work. He was hired to record Damnation Alley in 1977 after audaciously telling Jack Smight, who was directing the picture for Fox, that if he didn’t prefer his work to their regular Mixer (who was unavailable at the time), they should fire him. This was his first studio picture.

Glenn (Rusty) Roland: The Sound Department at Fox got the dailies in from the location recordings and were amazed at how totally perfect they were. [They] didn’t need any additional work ’cause Bruce, you know, was a perfectionist right on set.

Using all the tricks and specialty equipment he had developed for commercials, Bruce produced an excellent track that needed little adjustment in Post. For commercials, he had been a NABET mixer but this project gave him the IA Signatory days he needed to qualify for IATSE membership. After his acceptance into IATSE Local 695, Bruce was able to work on studio pictures.

He worked with Cinematographer John Alonzo on FM and it was Alonzo who recommended him to Director Martin Ritt for Norma Rae.

Norma Rae cemented his reputation as a Sound Mixer of remarkable ability. Much of the action took place in the din of a working textile mill and Ritt’s expectation was that Bruce would only be able to get a scratch track in that environment but even that was not at all certain. On the location scout, he used a Radio Shack sound level meter and measured 103 dB on the machine room floor. That’s a deafening racket but not so loud that people couldn’t communicate. Mill workers wore custom-fitted ear protection in the machine room and he watched them as they would approach one another and speak directly into the other person’s ear. Even then, only the person listening could hear what was said; it was essentially private communication. He had principal actors fitted for ear protection by the mill and specified that the plugs should be molded around his 26 27 miniature microphones. Rather than stringing the earplugs on a cord, he sourced especially thin microphone wire and used that both as a neck-loop and to carry signal to the transmitter. Ritt naturally staged the action to match normal behavior in the machine room and the actors would holler their dialog into a microphone only an inch or so from their lips. While the results didn’t have the quality needed for a production track, they were quite sufficient as a guide track..

Bruce made another key contribution to Norma Rae. Near the end of the film, Sally Field as Norma Rae has a confrontation with the management of the mill and is carted off by police officers. It’s a climatic scene with dialog from several characters and would be chaotic if characters could only communicate by screaming in each other’s ears, one on one. Bruce reviewed this with the Director and encouraged him to find a way to shut down the machines for that scene. Nothing of the sort was scripted but Bruce’s suggestion came a few weeks prior to filming the scene so Ritt had some time to consider the advantages. He and his writers structured the scene so that, after Norma Rae displays her “union” sign, the workers, one by one, shut down the machinery. The scene played very much as Crystal Lee Sutton, the actual Norma Rae, recalled it but it hadn’t been part of the first draft of the script. This work stoppage is arguably the key moment of the movie and intensely powerful.

Each project in a career brings its own set of challenges. Bruce evaluated each circumstance individually and adjusted his approach for the best result. He used whatever tools or techniques would produce a good track.

Nick Allen, CAS: It was so [much] fun to work with Bruce because he would use lots of tools. With Bruce, you’d open the truck and, which of the forty-seven microphones would you like to use today, kid?

Glenn (Rusty) Roland: Bruce was always doing that on sets, he would always hide microphones everywhere … he was always placing those huge, I guess they were Neumann, those huge microphones …

Nick Allen, CAS: He was putting U-87s in the middle of a set and cranking it and getting real dialog they’d use in the movies. He did the wackiest, most obscure things but, like you said, his ears said, you know what, they’ll use that in the mix …

In some cases, the simplest method was the best choice but Bruce was not afraid to swim against common practice if that yielded results. For 10, there was a scene with Julie Andrews singing and Dudley Moore accompanying her on piano. Although he experimented with a plant for the piano, he ended up recording it off Dudley’s radio microphone. Post Production didn’t believe at first, that the piano was recorded on a wireless but he was fearless if a scene sounded good to him. Conversely, hiding microphones the size of a Buick, if they sounded good, was, for him, entirely normal.

Nick Allen, CAS: And he had a “keep trying” attitude. He taught me that if take one was wrong, put something else in on take two. When you find something that’s getting close, tweak it, don’t change. There was this path of methodology.

Regrettably, as Nick went on to say, the pace of production is now so relentless that the first take is often it and there may be no opportunity for adjustment. Whenever possible, he was a bold experimenter in the pursuit of excellence. It’s a dangerous business to be running EQ in a shot—and changing it on the fly, no less! Multi-tracking was not an option at the time and there was a risk of over-compensating and spoiling a track. Nobody gets it right 100% of the time, but Bruce had an enviable batting average. He worked to maintain that record both by doing his preparation carefully to be sure he knew what to listen for and also by keeping his hearing in top form.

Douglas Schulman, CAS: Another thing Bruce does, you know, I don’t know if he’s still doing it, but he would always wear earplugs in his ears when he wasn’t wearing his headphones.

Glenn (Rusty) Roland: Bruce was very protective of his hearing. If we were in a loud place, he’d have earplugs in or something. He did not want to get his ears damaged by bad, loud noises. He had incredible ears for sound.

Bruce regarded his ears as his primary instrument and took pains throughout his career to protect them.

Douglas Schulman, CAS: He didn’t have a problem, I mean, with teaching you something but Bruce was always funny. If he was going to show you something new, he would say, “Now, this is a secret. Don’t tell anybody.”

Nick Allen, CAS: I went to Berklee College of Music, very briefly, only for a couple years. I was studying production engineering and jazz piano and I didn’t learn as much there as I did from being around Bruce.

In the course of his work, Bruce acted as a mentor to several of his boom operators. He recalls a time with Nick Allen when they spent half a day listening to windscreens and cataloging how each one slightly altered tone and ambiance. This kind of attention to detail might seem obsessive but it provides the foundation of understanding that permits responding rapidly to challenges.

Douglas Schulman, CAS: The thing that I learned from Bruce is actually how to listen to stuff … we tend to, with our minds, focus on things and take things out and what I learned from Bruce was to listen more like a microphone which hears everything.

The summation or direction of a 37-year career isn’t often represented in a list of credits. This is especially true with crew people who don’t usually initiate projects but must accept or decline offers as they are available. Bruce Bisenz’s career was more eclectic than most, ranging from Reds, a grand historical vision spanning continents (he did the scenes shot in California) to intimate portrait films like Without Limits, the Steve Prefontaine story. He did performance films like Purple Rain with Prince and he continued to do documentaries like The Making of a Legend: Gone With the Wind. (I’m pleased to have worked with him on a few of the smaller projects like Legend.) Other highlights included Captain Eo and Smooth Criminal/Moonwalker where he engineered the off-speed playback, not a common thing at the time, so that Michael Jackson could dance in slow motion and still be in sync with the music. The one common element of all these projects is that they all received his focused attention and considerable thought. Bruce never “walked” through an assignment; he evaluated each one to consider what an audience should hear on the track and worked to accomplish that. It was just this intelligence that Robert Towne recognized in that first interview with Bruce for Personal Best.

Glenn (Rusty) Roland: Oh yeah. I always thought Bruce was, he was just the best, I mean when you worked with him. It is different than others, that’s for sure, but in a very good way.

Robert Towne: You know, I just said, this is what I need and he somehow delivered it. I honestly can’t say enough good about Bruce in terms of what he brought to his work.

The first thing that Bruce said to me when I interviewed him was that a “successful career implies a successful retirement. If you die in harness, that’s not a successful career.” He’s been retired for eleven years now but continues to be active. He records a live swing band weekly. The Jerome Robbins Dance Archive accepted for the New York City Library the photos of performing flamenco dancers he has been making over the ten years of his retirement.

Interview Contributors

I thank Bruce Bisenz for making himself freely available and for supplying the images that illustrate his profile. I’m also grateful to the following colleagues who made themselves available for interviews:

Nicholas Allen, CAS was a Boom Operator for Bruce starting with Crimes of the Heart through Gilmore Girls. He works today as a Production Mixer.

Glenn (Rusty) Roland, a Cameraman/Director, remembers working with Bruce on motorcycle documentaries like On Any Sunday. He worked with Bruce on commercials and brought him in to do The Making of a Legend: Gone With the Wind.

Douglas Schulman, CAS was Bruce’s Boom Operator on Personal Best, Heart Like a Wheel, Something Wicked This Way Comes, Captain EO and many others. He is a Production Mixer today.

Robert Towne is a Writer/Director. He hired Bruce for Personal Best, Tequila Sunrise and Without Limits.

Jeff Wexler, CAS considers Bruce a mentor; his first assignment in sound was booming for Bruce.