by Scott D. Smith, CAS

Introduction

As a production mixer, sooner or later (if it hasn’t happened already), you will receive a call that goes something like this: “Hello, this is Charlie (usually some overworked and underpaid editorial assistant) calling from the editorial room of Clueless Pictures. We are going through the sound elements for delivery to sound editorial for the show Mission: Impossible XXXVII, and it appears we are missing the iso tracks for shoot days number 200 to 225. We wanted to check to see if there is any possibility that you might have backup files for those days.”

A brief silence ensues while you try to remember exactly what show he is talking about, as it has now been about six months since production wrapped. You respond, “Geez, I don’t know, I will have to check and see. That was some time ago—there might be a backup at the shop. Didn’t they make backups of the dailies in editorial?” More silence, and Charlie replies, “Um, I guess not. I don’t know—I was hired on after the fact. We only have what was delivered to us for ingest into the Avid. We were under the impression that backups were being made on set.”

What the Hell Is Digital Asset Management—and Why Should I Care?

Virtually unheard of 15 years ago, Digital Asset Management (referred to as “DAM” in the trade), is the catch-all term used to describe the process relating to the storage, access, retrieval and migration of digital media files. While “Digital Management” systems have been in existence since the invention of IBM punch cards and magnetic data tape systems, the terminology related to Digital Asset Management systems typically involves files described as “Rich Data” or “Rich Media.” These could include image files, video files, audio files, CAD files, animation and the like.

In the “bad old days” of analog sound recording (including that of film-based cinematography), the “assets” of a production typically consisted of sound elements recorded on magnetic tape or film and optical sound negatives, along with various picture elements (such as camera negatives, interpositives, internegatives, opticals, etc.).

Sound Elements

| 1. 3M 1/4” audio tape (on hub) 2. External hard drive 3. Quantegy 480 1/4” audio tape (7” reel) 4. FPC 16mm magnetic film 5. Audio Devices 35mm magnetic film (1000’) 6. Western Digital pocket hard drive | 7. San Disk CF card caddy 8. Maxell DVD-RAM disk 9. Zaxcom Deva hard drive 10. Maxell DAT tapes 11. Jaz drive & cartridge 12. 3M 200 1/4” audio tape (7” reel) |

Properly stored, these elements could last for many years, allowing for the restoration and “versioning” of films. They are, however, prone to degradation. Photographic elements in particular are notorious for issues related to color dye fading (with the exception of Technicolor IB), and the base materials used for both film and tape suffer from problems of shrinkage and warping. Further, triacetate base film and tape stocks suffer from problems related to “vinegar syndrome.” There is also the well-known issue of “binder hydrolysis” (known as “sticky shed”), which can render a magnetic recording virtually unplayable unless treated. These problems are not confined to just analog recordings either. All tape-based digital recordings (PCM, DAT, DASH, DTRS, etc.) suffer from similar issues. The only difference in the case of these formats is that problems in reproduction will render the recording completely unplayable; the digital converters simply mute when they encounter data past the threshold of error correction. Analog recordings, on the other hand, have a much better chance of being recovered (albeit degraded), even in situations where the carrier material is damaged.

For example, a 35mm magnetic recording could suffer issues related to base warp, incorrect head azimuth, and vinegar syndrome, but in the hands of an experienced sound archivist, will still provide a reasonable facsimile of the original recording. Conversely, a digital tape suffering from base damage can render it totally unplayable, with no chance recovering any part of the signal!

While file-based digital media avoids the pitfalls noted above, it is not without its problems. The most obvious of these is that if the physical carrier containing the data (hard drive, LTO tape, optical media) becomes damaged even slightly, it could result in the total loss of the program. Therefore, any successful digital-based archival strategy requires at least one backup of all the assets deemed to be important. This means that the storage requirements are virtually doubled, as is the storage cost. Further, rapid changes in media file formats and conversion technologies can quickly render both files and management systems obsolete, further adding to the overall costs pertaining to both migration and storage.

What Is a “Rich Media” File?

A “Rich Media” file is distinguished from more traditional digital files in that they typically are visual or audio data of some type, as opposed to files which are primarily text based (such as a Word document), or contain only binary code. While these file types are not mutually exclusive (for example, a Word file might have embedded images contained along with the text), Rich Media files are usually composed mostly of visual and/or audio elements, and are sometimes contained within a file “wrapper” or container. This “wrapper” might contain additional metadata or data that interfaces with a specific program used in conjunction with the file being addressed.

A prime example of a file wrapper is the MXF (Material eXchange Format) file standard, which allows for additional metadata (such as timecode) to be embedded along with video and audio data. While the video portion of the file could be encoded with any number of codecs, the wrapper itself is designed (at least in theory), to allow exchange among any systems which support the MXF file platform.

In a similar fashion, there also exist variations of some basic media file types (such a variations of audio WAV files), that can be played out without the need for a specific proprietary program, but may contain additional “chunks” of data within the file header. The BWF file format that is now used almost universally in audio recording for film and video is typical of this kind of “extended” file structure. Further, a file such as a PDF may contain embedded photos or Flash video, in additional to text elements. It is because of this blurring of distinctions between what might be construed a “Rich Media” file, as opposed to a basic “document” or text file, that has further muddied the context used to describe DAM systems.

In practical use, however, DAM systems are typically employed to manage large files encoded with visual or audio data, anything from a simple MP3 or Flash video, all the way up to full uncompressed hidef video. So while there could be a variety of file formats and codecs contained within a DAM system, an overall integrating structure is still needed to manage the competing file types. This has given rise to some highly complex DAM systems, which in many instances are expensive proprietary solutions designed for large clients such as broadcast media outlets.

The Dalet News Suite, manufactured by Dalet Digital Media systems, is a typical example of a dedicated system. This system employs a unique “container”-based approach to handling news content that might be repurposed for various channel outlets, allowing a producer or editor to access raw footage, and re-edit it for subsequent distribution in different markets. Similar collaborative tools exist in the world of post-production, such as the Avid Unity MediaNetwork system.

While these systems may vary in the way they are designed to access and move data based on user needs, they share a common thread in that they rely on a standardized file structure (using either external descriptive data or embedded metadata), to handle the task of determining exactly what a file contains. Therefore, while a cursory look at the file names contained in a project folder may reveal just a useless array of arbitrary letters and numbers, the database tied to those files allows the system to provide the user with a wide array of pertinent data relating to that specific file. In the world of film or video, the data might include such things as scene and take number, timecode, shot description, the date it was shot, camera metadata and comments from the director. There could also be additional data files such as lookup tables (or LUT’s), which allows the look of a shot to be controlled during the final color-grading of the production.

For these systems to function as intended, it is crucial that the metadata coding, file-naming conventions and folder structures be followed without any variations. Without this, the system will be incapable to tying together the various descriptive data with the corresponding files. If this correlation is lost, then the system will be unable to manage the tracking and movement of data as it makes from program origination through distribution.

That’s Great—My Head Hurts. What Does This Have to Do With Sound?

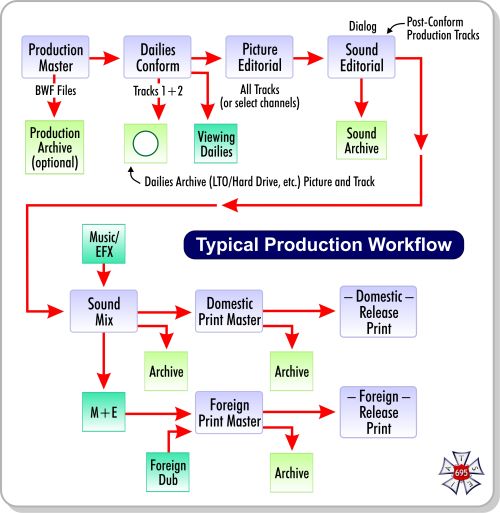

As film and video production has moved from an analog world to the realm of digital, the way of both image production and sound recording has changed radically. The tools used to manage workflow in the analog world are wholly unsuited to digital production. A typical example is how films are edited. No longer are there a bevy of assistant editors charged with tracking film elements using edge coding and a code book. Instead, all of this information is contained within a database linked to each of the individual audio and video files that make up a finished show. These may include raw picture files from set, associated production sound files, picture FX files, music files, title files, etc.

Just as all of these elements needed to be tracked in a master code book in the analog world, along with the editor’s cutting copy of the script, the same provisions apply to the myriad files that constitute a final program in the digital realm. It is therefore of crucial importance that a consistent overall structure for handling these elements be adhered to. Without this, at best, files will be impossible to manage, and at worst, may not play at all, due to file incompatibilities.

With file formats and systems constantly evolving, what used to be a pretty straightforward task 15 years ago has now become a minefield, with any number of problems lurking to trip up the unwary. In the analog days, a production mixer could pretty much rest assured that a tape submitted to post would get handled properly (assuming that the log was marked clearly). Worst case, maybe the heads were out of azimuth, or perhaps the wrong track would get transferred. This would happen long before sound editorial was involved in the show.

Despite some areas of standardization for audio file formats (with BWF mono or poly files being the generally agreed-upon format for most production), there still exists a wide variety of standards for items pertaining to timecode, sample rates and bit depth. Further, there is not as yet a fully defined format for how metadata is encoded in the BWF file header. Nor is there any industry standardization regarding file-naming conventions.

Therefore, it is vitally important that an agreed-upon set of conventions be established prior to production, and be adhered to throughout the run of the show. This is especially important when multiple units are involved in production, as material from all units will still need to be ingested into a common platform for editorial. Typically, these specifications will be supplied by editorial. If a show is just starting, it is good policy to shoot a sync test with the cameras and recorders to be used during actual production, and have editorial verify that everything plays well together. At the very least, it is important to get the required information supplied in writing from post-production.

In addition to defining such issues as file format, timecode, sample rate, etc., it is of equal importance to determine exactly who will be responsible for the task of file backups. Despite the endless meetings and phone calls that usually precede a production, this seems to be one area that no one wants to deal with. With so many people involved in the handling of files from the set to post-production, the area of data backup (especially of audio files) seems to get lost in the shuffle. While there are a variety of ways to approach the issue, as a mixer, it is important to define exactly what is expected from you in relation to making file backups of daily production material.

Despite the fact that file-based recording for production sound has been around for at least 15 years now, it is worth noting that most studios still don’t have a clear-cut policy as to how audio and video files are to be archived. In the days of analog production, no one would expect the mixer to maintain a set of backup tapes for a show. Yet somehow, due the perception surrounding file-based recording, the expectations have changed. While this makes absolutely no sense, frequently, certain assumptions are made by post-production in relation to production audio file backups. One of these assumptions has to do with backups.

Liability and Piracy—Why You Should Cover Your Ass**s

Despite the reams of documents that accompany the start of most productions (deal memos, non-disclosure agreements, safety policies, non-discrimination policies, auto mileage reimbursement, cell phone usage and hoards of other items the studio attorneys have dreamed up), there is seldom anything pertaining how production files are handled. While many productions prohibit the taking of personal photos on set, there is almost never any mention of what becomes of the files recorded by the sound department, which typically reside on one or more hard drives or removable media. Although it is understood that such recordings are the property of the production company, what exactly becomes of them is frequently ignored completely.

While this may be a non-issue in most production situations, there have been a few cases that might give one pause. Stories abound regarding instances where digital audio workstations have been rented from a supplier for the recording of a music artist, and subsequently returned with all the sessions files left intact! This allows anyone with access to the drives to simply copy the files and distribute them as they wish. This is essentially the equivalent of handing over the multitrack master session tapes. Occasionally, this oversight works in one’s favor (such as the instance where Michael Jackson’s recordings were found on a DAW hard drive after his death), but it can also become a major headache when the material ends up in the wrong hands.

Likewise, the failure to have a clear backup strategy in place can have equally heart-stopping consequences. There is no shortage of stories regarding hard drives containing crucial production elements being lost, damaged or stolen, resulting in days (or weeks) of work being lost. You do not want this happening on your watch.

Strategies to Help You Sleep Better

Despite the fact that many productions don’t have a clear-cut approach to file management, this does not mean that you shouldn’t take an active role in defining your responsibilities when it comes to the delivery and backup of production files. As everyone knows, when the manure hits the fan (and it will!), production will come looking for a fall guy. Don’t be that guy.

If production has not provided clear guidelines for how files are to be managed, you need to take it upon yourself to define your role in terms of how files are to be stored and delivered. Despite the fact that this is not exactly part of the job description, it is necessary to protect yourself when things blow up. To not take an active role in outlining your responsibilities is to leave yourself open for liability, which is not a situation you want to be in.

So, what are the specific steps you need to take in this regard?

1. If production has not already outlined all the steps for file handling, prepare a basic memo that outlines what you intend to do. This should include what medium files are recorded on (IE: on hard drive, CF card, or both). How they are delivered on the day of production (IE: CF cards handed off to DIT, CF cards delivered off to camera, DVD-RAM disks, etc.). If a film break is done during the day, will files be appended to the same roll or will a new roll be started?

2. State how logs will be delivered (paper copy, file, or both).

3. Outline what steps (if any) you will take in regards to making file backups, i.e., if recording to hard drive, will you make a daily backup or weekly backup or none at all?

4. If you are expected to make incremental backups on a daily or weekly basis, make note of how much additional time you expect this to take, so that you don’t start receiving questions from payroll about your timecard.

5. If files are being recording to hard drives (belonging to either yourself or a rental company), state what you intend to do at the end of production. If a production expects you to keep files after the end of shooting, clearly state what your liability is in this regard. You do not want to put yourself in the position of being liable in a case where production may come asking for backups, and you discover that you don’t have the files they are asking for.

If you are renting equipment from an outside rental company, it should be clearly stated that all data will be wiped from the hard drives before the equipment is returned. This will cover you in a situation whereby something from a shoot may suddenly turn up on the Internet. Additionally, if you are expected to hold onto files after production, you need to state that you are doing this as a courtesy to production, but in no way are you liable for their safety or piracy. (This is SOP for labs and post-production houses.)

6. If you do keep files after production has wrapped, state for how long you will keep them. (In this regard, it is also a good policy to notify post-production of your intent to wipe drives before you do it). No matter what the strategy, do not load files on any computer or drive connected to the Internet! No matter what your level of protection from hacking, this will prevent you from becoming a casualty of data theft. Files should always be stored on a separate hard drive, preferably kept in a safe place.

If you are operating under some kind of company structure (LLC, LLP or Corporation), you should submit these guidelines under the auspices of your company, so as to limit your personal liability. In no circumstances should you sign any document from production which holds you personally liable for the loss or piracy of media!

This memo should be delivered to the unit manager, the production supervisor, and editor. If delivering by email, make sure that they acknowledge receipt! (Personally, I prefer to make a printed copy and deliver it as well. This will save you in situations where somebody says, “I never got the memo.”)

When delivering files to the production office, be sure to have the recipient sign to acknowledge delivery. This will provide a clear chain of custody in situations where something gets lost. If sending media by a courier or shipping company, it is important that you request a signature upon delivery.

This may seem like a lot of extra effort, but the digital landscape has completely changed the way we operate and allows scenarios that would seldom occur in the world of analog recording. (For example, a production company would never expect the mixer to maintain copies of 1/4” production tapes.)

Having said this, you will of course be a hero if you take it upon yourself to make file backups of your own accord, and receive the call from post-production looking for them six months later! In this regard, however, you do not want to accidentally open yourself to liability in cases where files may end up in the wrong hands.

Housekeeping

Despite the move to digital, it has not relieved us of the burden of paperwork (in some ways it has made it worse). We still need to submit a sound report, whether as a paper log or digital file. In addition, it is now expected that we include basic file metadata in the header of each take. This usually consists of scene number, take number and track name, along with any basic notes. Unfortunately, this arrangement doesn’t always allow for easy changes after the fact.

While some recorders allow the metadata header to be edited after the fact, there are occasionally limitations as to exactly what fields can be changed. For example, in a quick scene change, you may accidentally forget to change the name of a track, so the file will bear the names from previous scenes. While tools such as BWF Widget allow the user to modify the metadata on external media after the fact, it does not change what is contained on the hard drive. Therefore, if you produce a file backup from the hard drive, it will contain the same errors, forcing you to make corrections on both the daily file media and the backup. Not how you want to be spending your weekend!

Further, in most current file-based recorders, metadata is stored as both a bext data chunk and an extended iXML header. If changes are to be made, they will usually need to be done separately for both. Therefore, it is always helpful to pay attention to the metadata that is recorded during shooting, so as to prevent the hassles of trying to correct it after the fact (easier said than done when it’s hour 14 of a grueling production). Hopefully, new tools will be introduced soon which will allow for easier modification of file metadata after the fact. The delivery of logs is equally fraught with complications that we never had to deal with in the days of analog. If paper logs are delivered, they frequently get separated from the data files during post-production (or get delivered after the fact). This is especially the case when sound files are delivered from picture editorial to sound editorial, which may be done over network drives, with no physical delivery of media. All the careful notes you made for sound editorial are now stuffed away in a box somewhere.

To keep yourself from being a victim of this scenario, it is helpful to provide a digital log of some sort along with audio files (this could be in the form of a scan of a paper log, a PDF of a machine generated log, an Excel file or text file). No matter what route you choose, having a log file kept with the media will always be appreciated by the folks in post. However, it is best to stay away from formats that are dependent on specific operating system platforms, as it is impossible to know in advance what systems might be employed down the line.

Further, as studios begin to archive productions on mass storage systems for repurposing of content, it will allow for the easy retrieval of the sound files along with their associated logs, without resorting to searching through paper logs.

Summary

As the digital landscape continues to evolve, it will become increasingly important to be cognizant of how the material recorded during production will be handled down the line. While practices put in place during the analog era generally remained the same for decades at a time, the same cannot be said for digital media. New technologies for both production and post-production can change almost overnight, with subsequent impact on how the scenario for production sound is played out. This is especially true when it comes to the physical media that data is being stored on, both during production, as well as subsequent archiving. Already, we have seen at least three major transitions for the physical delivery of sound files in the past 15 years (Jazz Drive, DVD-RAM, and CF cards), with more to come. It will be increasingly important for sound crews to be well versed as how data is recorded and delivered on various media, each of which has its own idiosyncrasies. As the production world becomes more “data-centric,” our role in how sound is recorded and delivered will have a major impact on how accessible it will be for future generations.

© Scott D. Smith, CAS