WAGING WAR:

The Production Sound Team Goes Into Battle with Christopher Nolan on Dunkirk

by Daron James

George (Barry Keoghan) and Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance) aboard the Moonstone as three Spitfires fly overhead. Photos compliments of Warner Bros./Melinda Sue Gordon

Nothing came easy for anyone on Dunkirk, including Production Sound Mixer Mark Weingarten. “It was challenging recording Nolan’s latest film, but it’s why we take the job and do the work,” says the Oscar nominee. This is Weingarten’s second picture with the English director, having worked on Interstellar—the sci-fi epic, starring Matthew McConaughey—which filmed in difficult locations of Iceland and Canada. But even with that familiarity, and over twenty-five years of experience, this production was his most difficult film to date.

“Dunkirk is very well known to every British schoolkid. It’s sort of the British equivalent of the midnight ride of Paul Revere every American child knows,” says Weingarten as we ate lunch at a Silver Lake restaurant on Sunset Boulevard. Taking place in the early months of World War II, the historical moment dates back to May 1940 when Nazi Germany pushed back British, French, Belgian, Scottish and Canadian troops to the beaches of Dunkirk, France. Surrounded by combatant tanks and aircraft, the only way to evacuate the nearly four hundred thousand troops was to send out a call for private naval vessels to help out the Royal Navy—including small craft that could get close to shallow waters. British civilians responded in droves joining the effort in one of the greatest stories in human history.

Nolan envisioned the account as a cinematic race against time—immersing the audience in the life-or-death situation by land, sea and air—while unfolding the narrative through the eyes of only a few characters.

Christopher Nolan (center) on the set of DunkirkProduction started in May of last year and landed on the beaches of Dunkirk. Nolan and Cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema (Interstellar, Her) deployed IMAX and 65mm film cameras for the visuals—shooting primarily handheld and three hundred sixty degrees—making placement for a sound cart difficult with strong winds and surf becoming the bigger enemies.

On Weingarten’s cart, a Zaxcom Deva 5.8 and Mix-12 complemented Lectrosonics wireless for the beach work. For boom, run by Tom Caton on the French unit, a Cinela Piano was paired with a Sanken CS-3e or Sennheiser MKH 416, depending on the situation. “The winds were a consistent thirty mph, so my older Zeppelins were not up to par. I first bought the Rycote Cyclone but then switched to the Cinela because the thing is amazing,” he continues. “It’s totally acoustically transparent in the most extreme wind. It comes with three levels of sound protection—we mostly used the middle weight—and it sounds like there was nothing on the mic.”

Dominic Happe with boom aboard the Moonstone with 1st AD Nilo Otero & 1st AC Bob Hall’s back

Moving from the thousands of extras on the beach to the east mole, a stone breakwater with a wooden structure on its top to offload ships, sound found themselves in tight quarters on the over thousand foot pier. Because of the limited space, Weingarten went to a simple over-the-shoulder rig, using a Zaxcom Fusion 12 and Lectro wires. “Often, the waves of the North Sea would come right over our heads, completely drenching us,” says Weingarten. Several boom mics and poles were completely destroyed. “Luckily, our cable guy, Gautier Isern, had a relationship with Paris-based VDB, the boom poles we were using. Over the weekend, he would take them in to get fixed and bought replacements. One of the poles we gave them was the worst thing they had ever seen. We were very proud of that.”

Nolan on set with Fionn Whitehead as Tommy (sitting)When the sound team couldn’t run a cable—the preferred recording method for Nolan—wireless frequencies, were hindered by neighboring interference. “In every direction on that beach, you’d see windowless military-styled buildings with huge communication towers on top of them,” notes Weingarten. “I couldn’t use my Lectrosonics Venue in my bag configuration or my larger antenna system, so my only means of finding usable frequencies was scanning with the UCR411. The problem with that is it doesn’t pick the best frequency for you, and instead, you have to select something that looks good.”

Mixing the mole scenes, the team couldn’t work off a nearby boat because the tidal change and the camera were sometimes twenty-five feet away. Wires interchanged with booms during close-ups, with Weingarten using the knobs on the Fusion 12 for the dailies mix. “There were these long, six-person scenes, and while I’m not very good mixing with the knobs, we were still able to record the dialog under those conditions without needing to loop it.”

If any unforeseen challenges or circumstances arose, Weingarten communicated them to Sound Designer/Supervising Sound Editor Richard King. “We were able to capture some M/S stereo recordings on the beach and get the soldiers’ reactions. We also recorded the vintage Royal Air Force Spitfire planes on set, but the planes’ engines were not original and needed to be later replaced in post. We also recorded many of the ships, some of which were actually there during the evacuation of Dunkirk.”

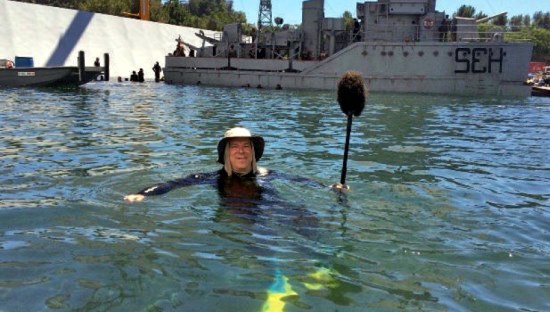

Larry Commans scuba booming in the tank at Falls Lake at Universal

From Dunkirk, production shifted to the Netherlands on the artificial lake of Ijsselmeer to shoot on calmer waters for scenes with Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance) on his Moonstone vessel. The belly of the forty foot boat served as the mixer’s office while the camera crew sometimes worked on another ship using a twenty six foot-long, gyro stabilized, telescopic crane called the Edge to mount the IMAX. Van Hoytema would sometimes board the Moonstone with the 65mm camera for handheld work on the pitching seas.

Frequency issues cleared up for the recordist and Dominic Happe joined as his boom operator. Weingarten paired the Fusion 12 with a Mix-8, a Schoeps CMC6 MK 41 and DPA lavs to mix the dialog between Mr. Dawson and actor Cillian Murphy, who played one of the shivering soldiers picked up along the way. “It wasn’t as rough as an experience, but the little boat couldn’t take much—it would pitch left and right. While we were shooting, periodically, the captain would yell down to come up when he thought we might topple over in fear that anyone would definitely drown if the boat went over,” mentions Weingarten.

Mixer Mark Weingarten filled with optimism with his cart, Mix-12 & Deva 5.8

He also suggested turning off the boat’s motor to help record clean dialog. “In reality, the boat would be running, and during prep, I found out it sounded the same as a city bus. I thought it would be better to place the engine noise in later to save the dialog and Chris agreed. We ended up having a marine crew tow the boat from another vessel— those guys were super helpful.”

From the Netherlands and shooting on the English Channel where as many as sixty-two boats gathered to film the ships crossing, the company went to Stage 16 at Warner Bros., preparing to enter the largest water tanks in the world. Boom Operator Larry Commans and Sound Utility Zach Wrobel came aboard and dressed in full scuba gear to squeeze through bulkhead heavy sets, making sure gear didn’t get submerged.

“We used these old Audio Ltd. wireless devices that have an antenna sticking out the back. You can screw a Schoeps capsule onto it and it’s powered by a single 123 battery. It’s totally self-contained, very fragile, but when they work, they work great. They only have two frequencies, but we were able to use them for the entire stage shoot inside a Zeppelin,” explains Weingarten.

Since wrapping in October, Weingarten looks back at the experience as one that won’t be forgotten—chalking it up to the fantastic crew and how they all bonded together to get each other through it all.