File Formats for Music Playback

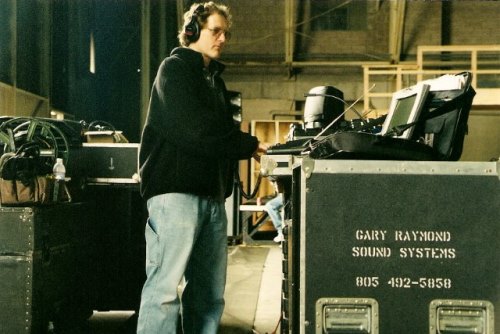

by Gary Raymond

I was asked to discuss optimum file formats for Music Playback (PB). This is an important topic that continues to evolve. Traditionally, the media and file parameters have mirrored the Production Sound Mixer’s formats.

When I started in the ’90s, most Mixers were using Nagras. As a result, the spare Nagra ended up being the logical (convenient) machine to also use for playback. As a result, tape speed was typically the same as the Mixer’s. There were definite limitations to the two-track format. When I worked on For the Boys in 1990, we had several large master shots that Mark Rydell, the Director, decided he wanted to shoot from scene beginning to end. Unfortunately, no one told Editorial as they had prepped all the reel-to-reel tapes as separate beginning, middle and end segments. To make matters worse, they didn’t know what combination would be desired so we had tapes with Orchestra-L, Bette Midler Vocal-R; Orch. & Bette-L, Jack Sheldon Trumpet-R, Orch. without Vocal-L, Jack-R and about a half dozen other permutations. I remember the

Editor bringing down this big box of about 50 seven-inch reels and us sorting through them. Then Mark announced he wanted to do the master shot all the way through. Duke Marsh, who was doing the playback with me, grabbed a second Nagra and we loaded the first part of the desired mix of the song on Nagra 1, the middle of the same song on Nagra 2, and stood by holding the pinch roller ready to let it fly on Playback. As Nagra 1 was playing, we had to start Nagra 2 at the correct spot and then, while it was playing, reload Nagra 1 with the end of the desired mix. I remember Mark Rydell came up to us after our successful playback day and said he wouldn’t do that job if someone held a gun to his head.

Editor bringing down this big box of about 50 seven-inch reels and us sorting through them. Then Mark announced he wanted to do the master shot all the way through. Duke Marsh, who was doing the playback with me, grabbed a second Nagra and we loaded the first part of the desired mix of the song on Nagra 1, the middle of the same song on Nagra 2, and stood by holding the pinch roller ready to let it fly on Playback. As Nagra 1 was playing, we had to start Nagra 2 at the correct spot and then, while it was playing, reload Nagra 1 with the end of the desired mix. I remember Mark Rydell came up to us after our successful playback day and said he wouldn’t do that job if someone held a gun to his head.

Keith Wester, who I worked with on Never Been Kissed, told me he started as a Playback Operator and, in those days, it was off a record. He’d find the groove (literally), mark it with a piece of white chalk and hope the needle didn’t bounce when he dropped it.

In the late ’90s, there was a flirtation with DAT (introduced by Sony in 1987). This was limited to the DAT formats. The DAT was more convenient in some ways than the Nagra (you could auto cue to preset markers) but it still suffered similar problems of any tape-based system. One was that the position coding information would actually get worn off with 20–30 repeated rewinds. Another unique disadvantage of the DAT relative to the Nagra was the fact that it couldn’t be edited the way reel-to-reel tape could be (with razor blade in hand). All editing had to be done “off line” and retransferred.

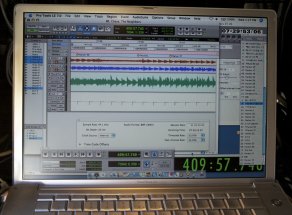

For this reason, in 1993 I switched to Pro Tools, a nonlinear computer-based system. If we had been using Pro Tools in 1990 when we did For the Boys, we could have loaded all the various playback combinations into one session and been happy clams. Pro Tools (computer-based recording, editing & playback) was vastly superior to tape systems as far as “function” (ability to manipulate the audio), although not necessarily “performance” (sound quality). It took a while for the computers to catch up with the sound quality of a Nagra; however, for playback applications, the tradeoff between function and (audio) performance was decidedly biased toward function. This is why the computer-based system (Pro Tools or similar) has become the de facto standard.

For this reason, in 1993 I switched to Pro Tools, a nonlinear computer-based system. If we had been using Pro Tools in 1990 when we did For the Boys, we could have loaded all the various playback combinations into one session and been happy clams. Pro Tools (computer-based recording, editing & playback) was vastly superior to tape systems as far as “function” (ability to manipulate the audio), although not necessarily “performance” (sound quality). It took a while for the computers to catch up with the sound quality of a Nagra; however, for playback applications, the tradeoff between function and (audio) performance was decidedly biased toward function. This is why the computer-based system (Pro Tools or similar) has become the de facto standard.

There have been many shows I’ve worked on where I had to do on-the-fly things that would have been impossible with an analog or digital tape-based system. This includes pitch shifting; I transposed the playback songs on the Britney Spears movie Crossroadsthe first day on set when it was determined the songs had been recorded in the wrong key.

On House, I used Pro Tools to provide PB for a slow-motion scene. This was a helicopter crash scene with dialog that the Director wanted to play in slow motion but not pitch shifted. The scene was shot in real time at twenty-four frames per second and then I did some tests at various frame rates to see how fast the actors could lip sync to their playback. Interestingly, it’s a function of the complexity of the particular spoken words. In this case, forty-four frames per second was the fastest the actors could sync convincingly. So, camera matched that frame rate and we shot the playback version of the scene. In post, everything was slowed down to normal twenty-four frames so, when viewed, it looked like the actors were talking in slow motion but with their voices’ normal pitch (something that would have been impossible with tape).

On Drag Me to Hell, a séance scene required reverse playback of the actors’ live lines. These effects could not have normally been done on set with a tape-based system.

On Drag Me to Hell, a séance scene required reverse playback of the actors’ live lines. These effects could not have normally been done on set with a tape-based system.

This brings us to the key issue, which is often either:

1) The PB material is not prepared for what is eventually desired on the set or, 2) more frequently, a live-record is used as the playback master.

In both these cases, the frequency sampling rate and bit depth must be decided.

When performing a live-record (as I did on Almost Famous, Rock Star, 8 Mile, or The Hangover), I usually match the Production Mixer’s settings. This is important if timecode will be used. That’s pretty straight ahead as it’s a “closed information loop system” between the Mixer and me.

When using straight PB tracks or files prepared by someone else, I also will usually consult with the Production Mixer and match rates.

However, even when you ask, you don’t always get what you requested.

The evolution of current Music Playback is that half the time I get music tracks from the Director’s Assistant off their iPhone five minutes before they want to roll. This is often the case even when I ask for a better format a few days in advance. They may provide me something in advance, but often it’s not what they ultimately want to use on set.

We are seeing a revolution in technological information acquisition that is being driven by computer media and smart cellphone capabilities. The ability to send information on a personal smartphone is conditioning the population to expect any bit of information to be instantly produced. The misperception is that all information is equally available. To a person who does not have to create information but simply download commercially available product, there is a lack of appreciation of the technical creative process. As a result, creative decisions that used to be decided weeks or days in advance are now made “on the fly” to suit the creative process

The good side is that this has allowed more spontaneous creativity on the part of the Director. The bad side is that there is an expectation that anything can be ready on the spur of the moment. So, in this sense, with regard to prepared material provided by others, we have de-evolved to the point where probably half the playbackonly projects I work on now are iPhone downloads. The first thing to suffer is audio quality, of course.

When prepping a film, television or commercial, I still ask for WAV or AIFF files when possible and an audio CD backup. A good conversation with the Editor (if there is one at that point in the film) can also be valuable.

If timecode will be used, I will match the desired rate which, of course, is dictated by camera format and, if no TC, the Mixer’s preference. With the aforementioned “iPhone” transfers, I’ll convert them to the preferred formats.

In live-record situations, the same pretty much applies. Obviously, the higher the sampling rate and bit depth, the better the sonic quality. However, conversion transfers with digital must be considered because converting from one sampling rate to another, whether up or down, degrades the sound quality. For that reason, I’ll normally record at the highest sampling rate that I think will be ultimately used. Getting the highest quality sound verses the convenience of various formats will continue to be an issue.

I’m expecting the next stage of this evolution to be direct brain scan downloads off the call sheet.

Happy Playback.

Glossary for highlighted word

Live-Recording The process of recording a musical performance on set rather than having the players mime to the playback of a studio session. Sometimes a live-recording will be used to generate a playback master that is immediately put into service to shoot alternate angles and closeups.