The Road to 600: The Evolution of Playback on Glee

by Phillip W. Palmer, CAS

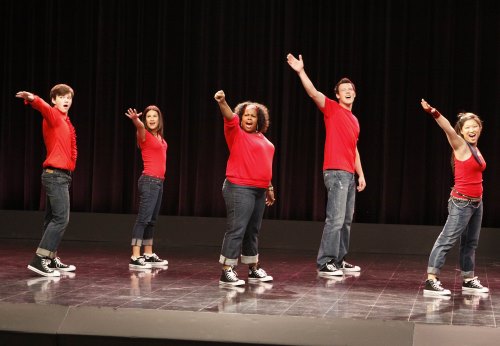

Pilot and Run of Show

When I got the call asking if I was interested in mixing a pilot for Ryan Murphy and Fox Television, the Producer asked an interesting question. He asked how comfortable I was doing a musical pilot, and whether I could manage the production side of things for a group of Producers who, while experienced, had never done this type of project before. Looking back now, almost five years to date, I had no idea what I was in for.

The pilot had elements of several processes: live-record, live-record to playback, playback only and combinations of all three. What we learned from the pilot, and how our company and cast operated, set the tone and process for a long journey. Soon after we started work on the pilot, we knew we were in for something special. Since October 2008, we have produced close to one hundred episodes and nearly six hundred musical numbers.

The music production and playback for the pilot was a completely different situation than the run of show. The music had mostly been prerecorded earlier, giving us time to figure things out and adjust our production process accordingly. For the run of show, music production has been a race against the schedule.

Glee still remains bound by the network episodic schedule, which we attempt to hold to eight days per episode. When the script is released, the music team goes to work immediately arranging and composing anywhere from five to as many as eleven musical numbers per episode. The temp versions are sent back and forth to our Executive Producers for notes and preliminary approval. Then the cast members are brought in to record their specific vocal tracks. The completed music mix is then sent back to our Producers. Upon final approval, the music goes to David Klotz, our Music Editor, for preparation of playback on set. The Pro Tools sessions he builds are specific to our purpose, which include timecode as an audio track, click, thumper, music mix, any specific and special music stems, vocal and vocal effects, and background vocal and vocal effects tracks. The playback session track count will frequently be upward of twenty-five or more stems.

Live-Records vs. Playback

The advantages of live-records are obvious on camera. The drama of the moment and the nuances of the performer yield an authenticity that is often undeniable. What we learned on Glee is that this works for us only sometimes. We discovered early on that repeated live performances, especially when sung “all out” take after take, have a detrimental effect on the performance as time went on. Essentially, after ten or more takes, the moment was lost, as well as the performer’s ability to continue to work through the day and into the next on a TV production schedule. We had to decide which songs needed to have this live performance effect, and plan our production accordingly.

In the pilot, all the Glee Club student auditions were recorded live on set including the piano, with the exception of “On My Own,” performed by Lea Michele. Her audition intercut with her singing the same song in several locations, and was prerecorded for playback and lip sync on set. The shower scene with Cory Monteith singing, “I Can’t Fight This Feeling” a cappella, was recorded live as well. Our vocal coach gave Cory a pitch and then we ran a thump track for tempo. The thump track is essentially a 40 Hz click track played at a low level through an eighteen-inch subwoofer. The 40 Hz thump can be removed later in Post by the use of a notch filter, leaving the vocal recording unaffected. The artist can feel and maintain a tempo and Editorial can easily cut back and forth between takes of live recording. The remainder of musical performances in the pilot were prerecorded and played back for lip sync.

Pro Tools

While there are many Digital Audio Workstations available to the Production Sound Mixer today, we use Pro Tools for several reasons, foremost among them being that the music production team uses Pro Tools for their recording process and we can easily modify their sessions for our use. We have found that the use of Pro Tools on the set has been an invaluable tool to our playback workflow. We can easily manipulate any session to match what we are currently filming and, if need be, send that same session back to the Music Editor so he can prep it accordingly for Editorial. We can easily do things such as change level and volume to match camera angles, or make music edits at the request of the Director. The Music Editor can then load our session files to see what we’ve done on set.

There has been an evolution to our playback Pro Tools sessions since the pilot. In the beginning we simply had a mix, essentially the Producers’ approved demo, with a click track added. As the seasons have progressed, we have added regular stems to our sessions that we find very useful. Our Music Editor adds a thump stem, which matches the click track, so we can assign a separate output for the thumper. We can do it on the fly, or program it in the automation to dump the music at any point and go to a thump to record dialog during the song. We also add a timecode stem as an audio track, which comes in very handy when creating any offspeed versions of the song. The timecode will always stay locked at any speed if it is an audio track and part of the session. We have the music stems combined as a mix, unless there is a specific stem that needs to be split out, such as a piano track. The vocal stems are all separated by lead vocal and effects. If there are six lead parts in a song, there will be six stems and six effects stems. We have the background vocals combined, but sometimes it’s difficult to distinguish the background vocals in the overall mix. Having the ability to boost the background vocal stem by 4 dB to 6 dB during playback helps our cast follow their cues. When the sessions are completed and sent to us, there are frequently dozens of stems to manipulate.

Playback Equipment and Installations

For the pilot, our playback gear on set was a simple Pro Tooks Mbox Mini audio interface and a MacBook. We made the most out of it, but quickly knew we had to improve on our rig to handle more complex playback situations. After the first season, we built a cart that had a dedicated Mac Mini, twenty-inch monitor, Pro Tools Mbox Pro audio interface, a backup Mbox Mini, Command8 control surface, Mackie 1402, Comtek transmitter for earwigs, Sennheiser receivers for VOG, and video monitors. This rig stayed fairly unchanged until an overhaul this past summer for our fifth season. The current playback cart has a new Mac Mini and monitor, MOTU Traveler audio interface, Lectrosonics Venue for VOG, Black Magic Smartvue Duo HD monitors, and the Mackie 1402 and Comtek base station from the older rig for audio distribution,earwigs and monitoring. Our mobile speaker complement consists of two JBL EON10 speakers for small sets and two Mackie SRM450 speakers for larger sets and exteriors. We built several lengths of custom speaker snakes so both power and signal can be run from the playback cart. Also included in the speaker arsenal is an eighteen-inch powered subwoofer for both thumper and low end when needed.

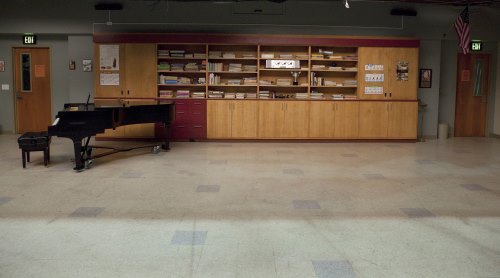

As we progressed through the first season we began to see the need for speaker installations in our main sets. Speaker placement became difficult as we battled with multiple camera angles, Steadicam 360’s, set walls and crew. We found the only good place to put them was up in the air. The first set to get this dedicated installation was the McKinley High Choir Room. This set saw the most playback by far, and still does to this day. For the Choir Room we mounted four JBL EON10’s surrounding the set. They are permanently hung and wired to a space just off set where we park the playback cart for 99% of the music on that stage. From that position we have “drive lines” to several places on the stage where we can drop a speaker and tie right in. This makes the music playback in the hallways very easy, as we are able to place speakers at either end of our long hallways without dragging cables through the set.

Season Two saw the construction of the McKinley High School Auditorium on stage. With this construction build, we installed six Mackie SRM450 speakers, two on each stage wing and a pair in the house, plus an eighteen-inch powered subwoofer for thumper. They are all wired, both power and audio, to a distribution amp and power control rack placed above the Stage Manager’s desk on stage right. They exist as a functional part of the set decoration. Both the playback and the main cart are set up in the same spot each time we work this set, so all the cable runs, including power, audio, video and bell/light, are permanently run underneath the set.

For Season Four, we built a new set for the storyline set in a New York dramatic arts school called NYADA. This new set is a dance rehearsal space, large and open, with high ceilings and giant windows that look out to Manhattan. We faced the same issues as with the McKinley Choir Room, and chose to suspend a pair of Mackie SRM450’s from above the greenbeds aimed down through the fabric ceiling and into the set. As with all previous installations, they are prewired with both power and drive lines to one central spot for the playback station.

The most recent set construction has been a New York City diner, built for Season Five on the backlot of Paramount. This was an incredible undertaking for the construction department, both in scope and speed. They used an existing space in the backlot but expanded up to create a two-story, high ceiling, Broadway performance diner. For this installation, the speakers are incorporated into the set design and mounted on the set’s west wall as part of the set decoration. We used a pair of the new QSC K10 speakers with the QSC yoke mounts for a permanent installation. We ran power and signal wires through the set walls to a drop point to facilitate connecting to the playback cart.

Playback Process

Most of the music scenes on Glee happen within a normal scene of dialog. Occasionally we have a stand-alone music piece but, for the most part, we fold the music playback into the dialog as best we can. The playback volume is often so loud it is at rock concert level. As we go from dialog recording to music playback, the transition is often abrupt and becomes difficult for Editorial. Anything that may happen within the song is lost due to the high playback level. We attempt to bridge this transition between dialog and music with a blending element.

The key to making this work is recording the elements we see during the playback as wild sound so Editorial and Post Sound can add these tracks to play under the prerecorded music. Due to our very tight episodic television schedule, Editorial doesn’t have the time to build the background noise and Foley for our multiple music scenes. To do this we make every attempt to do a “Foley Pass” of things like laughter, whistles, footsteps, hand claps, crowd applause, set pieces moving or falling, or anything that makes noise during the musical number. We record this wild track with the music playback at a very low volume. For the Editor, the Foley Pass becomes an important element in making the musical number feel real.

When we choose to record a performance live, we often prerecord the music stems and record the actor singing on set. The music is fed to the actor via earwig and we record the vocal as usual, with a boom microphone. We try, not always successfully, to leave the temp vocals in for the wide shots, and go into the live-record when we get into close-ups. In our experience, it saves the actor and the performance. I do my best to create a mix in the Comtek public IFB for the Director to get a feel for what we are recording. For the IFB feed, to the boom operators and set crew, I leave the playback track out or run it at a low volume. I split tracks one and two as a post-fader mix for Editorial, track one is the live microphone and track two is music. Everything is ISO-tracked pre-fader so it can be adjusted or rebuilt as needed.

Often we are tasked with strange and challenging playback situations. Midseason Three, we had a scene and musical number that took place at a swimming pool with synchronized swimmers. Having a beat to follow underwater is one thing, but having to do lip sync is another. Luckily, after some tests, we found the synchronized swim music equipment “Oceanears” worked very well for our needs. The swimmers and our cast were able to hear the playback feed from the underwater transducers. I was quite impressed by the clarity and the distance the music could travel underwater at nominal levels.

One script called for a musical number being sung from a golf cart while moving. That works well if it’s traveling a short distance, but that wasn’t the plan. They wanted to load down the golf cart with cameras and drive the entire length of the song, some twoplus minutes. We negotiated for an additional golf cart, placed a speaker with wireless receiver in the picture cart and transmitted from our “sound golf cart,” which slowly became the “everyone else” golf cart. We essentially did two angles several times, first leading then following. The playback rig was somewhat simple, a MacBook Pro, MOTU Traveler, and a Lectro UH transmitter. The speaker on the cart was a battery-powered Sound Projections SMP1 fed from a Lectro UCR411. We had a good time with this one. Certain musical performances call for special shots that require playback manipulation—specifically, off-speed filming for incamera effect. Frequently, we speed up both camera and playback by as much as three times normal. When the image is played back at normal speed and the music is laid back in, the artist appears to be singing in sync while everything moves in slow motion. This is achieved by speeding up both the music stems and the timecode stems. We transmit the high-speed timecode to a slate and roll camera, then playback as you would in a music video. Post can then manually sync the music to the displayed timecode as it’s locked in the session as an audio stem.

The Crew

Commitment and cooperation from the entire shooting company from the beginning has been the key to making this all work seamlessly (or what appears so). I can’t imagine what this would be like if the crew didn’t understand how challenging it is on a daily basis. It’s difficult for each department in their own way, and we respect and strive to work together to make it happen. We have had three Directors of Photography for the run of show: Christopher Baffa, Michael Goi and Joaquin Sedillo. Each one of them has worked with us to get what we need to achieve our goals, both with sound recording and the music. It’s a cooperative effort, as always, and I’m grateful for our working relationship. When our needs impact the way the show is shot, we have to have a plan and options. I can’t stress how important it is to have multiple plans of operation. My sound crew has undergone some changes since the pilot, but for the most part, has remained constant. Patrick Martens has been my Boom Operator for the entire run. Devendra Cleary was Utility Sound Technician and Playback Operator for the first two seasons, and then moved up to Playback only in Season Three. Mitchell Gebhard joined the crew as Utility full time in Season Three. After Season Three, Devendra moved on to mixing full time, and Jeff Zimmerman joined us as Playback Operator beginning Season Four. Without the unbelievable ability and flexibility of these people, I would be completely useless as their Sound Mixer. They show incredible professionalism on a daily basis and shine in their abilities to do the job. I provide the guidance, but they get the job done.

Glossary for highlighted words

Click Track A series of audio cues in time to a piece of music. Typically, the click track is generated in a DAW and used by musicians or dancers to keep time to the music.

Thumper A playback system to reproduce the beat of music as a series of low-frequency thumps. The tones are typically about 40 Hz so they may easily be removed from a track without harm to recorded vocals. A special thumper speaker system optimized for low-frequency reproduction is used to play the track. The thumps permit performers to follow the beat of the music without musical playback that might interfere with dialog recording. Originally invented by Hal and Alan Landaker for Warner Bros. Studios. (See 695 Quarterly, Volume 2, Issue 1, Winter 2010)

Stem A mix of multiple audio sources. Example: A blend of music and effects, without dialog. The use of a stem allows complex source material to be treated as a single unit in the final mix or as a temporary part of the process of editing and recording audio.

Mbox An audio interface manufactured by Avid for use with its Pro Tools software.

Command8 A mixing panel control surface manufactured by Avid for use with their Pro Tools audio editing software.

VOG Voice of God. A portable public address system that allows a Director to address groups of performers and technicians with an authoritative voice.

MOTU Traveler The Traveler is an audio interface for connecting multiple microphones, and other audio inputs, to a computer. It is made by MOTU (Mark of the Unicorn), a manufacturer of hardware and software for computer recording

Black Magic A manufacturer of speakers, amplifiers and signal processing equipment.

Earwig A miniature monitor designed to fit within the ear canal like a hearing aid.

Greenbeds A series of catwalks above the sets in a studio.

Foley Pass An alternative to the studio process of Foley recording. The Foley Pass is recorded on-set at the time of principal photography. At the completion of the shot, the AD, at the request of the Mixer, calls for a Foley Pass and the performers go through all of the motions of the scene but without dialog and either without playback or with the music played very softly. This makes it possible to record all the natural sounds as an element separate from the music and speech. The Editor can use these sounds to add a natural background to the scene. It is an expedient alternative to the more elaborate process of the Foley stage but it also can preserve some of the immediacy of the scene.

IFB Interruptible Fold Back: A system for supplying audio as it is being recorded to artists and technicians. The signal path from the microphones is “interrupted” before going to the recorder and “folded back” so it may be heard by the people involved in the process of making or supervising the recording.