Production Sound for Gone Girl

by Steve Cantamessa

My first impulse when the editors of the 695 Quarterly called to ask if I would write a piece on doing production sound for Gone Girl, was to pass and finish my round of golf. More thought and my wonderful wife’s prodding changed my mind but presented me with my next quandary: though I try to keep up with the tech end of my craft and, with affectionate apologies to Mike Paul, my go-to guy for technical matters, production sound is not a terribly literary topic. A microphone with a skilled boom operator in control will render the best sounding track. Not always a doable task these days. It was a pleasure to work on a project that allowed us to use this technique. I spoke about penning this with a friend who reminded me that I have now become one of the new “old guys” and that I should just write what I know. So here we are.

Before my interview with David Fincher, I didn’t really know much about him, other than that I enjoyed his films and the work of his sound designer, Ren Klyce. That they sought me out was a compliment in itself. Thanks to my dad Gino’s lifelong involvement, cinema has been part of my life since before I was born. Talking with a respected director like Fincher promised to be interesting at the least. We sat down and I instantly saw that he knows what I do and has an informed opinion of how he thinks it should be done. Sadly, these days many may think they know what we do and how we do it, but they are usually mistaken. David Fincher knows. We discussed my approach to things on the set along with various advances in technology, and then he asked me to do the show.

It didn’t take me more than a couple of hours into the first day to realize that David Fincher was that rarest of birds these days—a director who does his homework and knows exactly what he wants when he gets on the set. And I mean exactly. Too often these days, many directors like to temporize important decisions. Others look at the call sheet and check things off and still others never seem to want to go home. On a Fincher movie, it is clear that everyone on the set has the same goal: to do his or her best work in order to make the best movie possible. Fincher crews his shows with the best people based, not on their ZIP codes, but on their body of work. From DP Jeff Cronenweth to Costume Designer Trish Summerville, everyone was helpful and mindful of the big picture, not just his or her own tasks. He understands that such efficiency on set will save far more money than any state tax credit ever will. He shoots his movie, not a corporate schedule.

Gone Girl was, I believe, the first show to use the Red Epic Dragon—a 6k camera capable of stunning imagery. As with the “first” of anything, there were issues. Specifically, considerable fan noise emanated from the front of the camera, where the actors usually are. The temperature of the chip in the Red was crucial, and seventy-two degrees was the magic number; once the camera readout on my video assist monitor went to seventy-three, I knew things were going to get noisy. Happily, the people at Red were most helpful. Though we started shooting in Missouri on mostly exterior locations, I knew that once we returned to LA for stage work, that fan noise would pose a big problem. Having been around the block a few times, when I explained this to the folks at Red I assumed that they wouldn’t give a damn about some sound mixer’s problems, probably being up to their own back ends with image tech problems. I was wrong. They listened, they asked questions and they wanted to hear my ideas. I told them that the fan noise coming out the front was a big issue and that it needed to be re-routed in some way. By the time we had returned to California, they had designed and built baffles that mounted to the front of the camera, routing the “sonic exhaust” around the side and then out the back. I was genuinely thankful and impressed that they cared. Most importantly, it worked.

The movie is wall-to-wall dialog, and my Boom Operator, Scott LaRue, was a busy guy; personal relief and lunch were the extent of his downtime. Our utility man was Brad Ralston, always a big asset with the gear and frequently serving as Second Boom Operator. Scott and I have been together since about 1992, so any discussion of how a shot is to be done is usually quite brief. Scott tells me how he sees it and I say, “Whatever you think.” There are those few occasions where I ask him to wire someone, but such requests are sometimes unwelcome. I do recall that when I was booming, I hated it when a mixer would tell me to wire someone I felt I could easily get with the boom. It must be a boom operator thing, but the fact is that he’s been putting me over for years and I am truly grateful.

It seems like we were always either rolling or setting up. To repeat, Fincher does his homework. The sets in Hollywood were beautiful and well built, but without greenbeds. It’s just the way it is now, most sets have ceilings and lighting is done differently, but booming on a ladder over a wall through a slightly raised ceiling piece certainly isn’t the most elegant approach.

HARDWARE NOTE: My standard package consists of a Cooper 208 mixing panel, an Aaton Cantar X2, Lectrosonics 411 radios with SMA transmitters, Tram lavaliers and 416s on booms transmitted via Lectrosonics 400 transmitters. And, of course, plenty of IFBs for the Director, Script Supervisor, Camera and Producers.

Even with all the dialog we had to record, I can’t recall David ever telling our department how we should do things. Again, Fincher’s hiring philosophy: he made it clear that being streamlined was important. Just do the job to the best of your ability without making everything into a sound issue. Find problems during rehearsals and get them solved while the DP is lighting so that, when the actors step in, you are ready to go. I don’t know how others do things, but this is how we always work. I can only judge from what I saw when I was booming. There’s a lot to be taken from having seen the likes of Kirk Francis, Jeff Wexler, Bill Kaplan, Eddie Tise and my dad Gino. These guys got to the top because they are professional filmmakers, very good at a most unique craft.

Back to Fincher: ask him a question and he’ll give you an answer immediately without any doubt or hesitation. This makes for a far more rewarding way to spend the day than the currently popular “Oh, just wire them all.” On the few occasions where he ran a tight camera with a wide shot, he would roll ten seconds of a clear frame and then have us bring the microphone into the shot. The ten seconds of clear frame provided a plate he could use to remove the microphone from the wide shot so the sound would not be compromised by the shooting plan.

Everyone involved in Gone Girl respected one another’s department and worked as colleagues. The focus and intensity on Fincher’s set benefited our department immensely. The actors never complained about wires. The Electric Department never jammed a generator up our butt. We never had to ask the dolly grips to quiet a track. The effects people were preternaturally aware of any sound implications. Locations were pre-scouted by the Locations Department for any sound issues, and those problems were solved before we got there. The sets were always dead quiet. For instance, we had a practical police station set located on a busy street in Culver City. David had the Construction Department build vestibules at each of the doors to the outside so we might have significantly diminished traffic noise yet still see extras come and go.

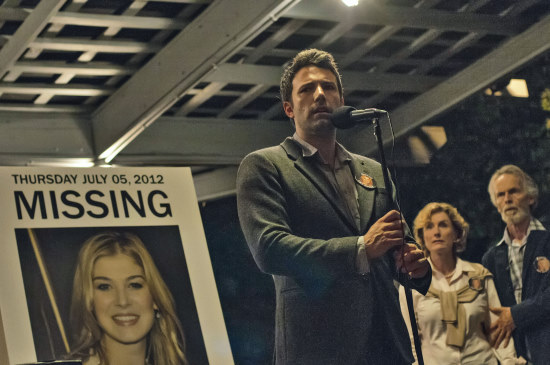

The scene with Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike (Nick Dunne and Amy Dunne) in the shower was the one place that was a bit challenging and was the only set where David couldn’t arrange things to our advantage. There was quite a bit of dialog at a low level with water running the whole time. The FX Department was helpful by painting “hogs hair” the same color as the tile. This allowed us to quiet the sound of the water hitting the tile floor and, being the same color, didn’t adversely affect any of the lighting. They also plumbed the water lines and packed them with sound-absorbing material to ease the sound of the water running through the pipes. The Construction Department removed out-of-shot glass panes as we worked so Scott could get the microphone into the shower and get the dialog. Again, everyone helped.

Some of the questions that come up when someone finds out that I mixed Gone Girl are fascinating to me. One is about the number of takes. Granted, he does a lot of takes but what’s the big deal? There is always a reason for them. Any direction I heard him give to an actor, or any department for that matter, was concise and thoughtful. The second question is regarding the sound style used on the dialog throughout the film. I wish I could answer this but I wasn’t there in Post; Ren Klyce, the Re-recording Mixer, would have the answer. What I do know is that David likes to use sound, even the dialog, to create certain moods and feelings that do not follow the normal rules. Everything you see and hear in a Fincher movie is intentional and controlled by David’s sensibilities. You may like the style, you may not, but I assure you that none of it is due to a mistake, laziness or lack of attention.

Those who know me know that I would make a poor courtier and seldom sugarcoat things. That said, I enjoyed the Gone Girl experience and got immense personal satisfaction from working on such a good film that people will enjoy watching. Working with good actors, talented technicians and a good director is all any sane person in this business could or should ever want. It is no mistake that nearly every review of Gone Girl includes mention of the high quality of the technical aspects of the film. David Fincher showed the good sense to hire from the best talent pool in the land to get what he wanted. Now, about my golf swing…

Glossary of highlighted words

Greenbeds A series of catwalks above the sets in a studio.

Hogs hair A woven filter material for heaters and air conditioners, used on sets to soften the sound of water droplets hitting a surface.