by David B. Wyman CAS

Greyhound was to be shot both practically on a real WW2 destroyer named USS Kidd, in a floating dock on the Mississippi River at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and on stage where the pilothouse, radar/command center, and the sonar room sets were to be built to scale.

After my first phone meeting with Aaron Schneider, our Director, it was apparent that he was not only going to be supportive to the Sound Department but really wanted to explore doing as much real-time audio as possible. Meaning, as much sonic interaction as possible between on-screen and off-screen actors, including set-to-set communication for twin units shooting simultaneously, simulation of radio broadcasts, real-time ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship conversations and loud sound F/X of the war action.

During the start of my prep, I watched as many WW2 and naval movies as I could to better understand the scope and process of the work.

Aaron was adamant that everything should be period-correct, including all props, costumes, and sets. Our pilothouse set and CIC set contained all of the same equipment found on the USS Kidd, which made for some really tight quarters for the actors and crew.

Luckily, Ed Borasch was our prop master, he and I have worked on several movies together. With careful coordination, I was kept aware of the key props our actors would be wearing/using during filming, and as each prop was locked in, I was given access to them to study and understand how they could be modified to suit modern filmmaking needs while maintaining period looks.

Playback Amps and Mixers for VOG and Sound FX, Comms Utility controller.

The same was true for the construction of our two main set pieces, as equipment was installed, I was given access to see how we could modify them to allow them to function practically for seamless audio use while shooting.

I was fortunate that production was onboard and I had enough prep available to make the Director’s dream an audio reality.

Firstly, I spent a couple of days onboard the USS Kidd scouting and understanding just how the internal communications, radio telephone, sonar, and ship-to-ship actually worked in 1940. Thanks to a very knowledgeable crew there, I was forming a picture of how to make our 1940’s replica ship sets behave as if they were at sea during wartime.

The first challenge was to figure out a way to make the “Bitch-Box” work. This is the internal communication device that allows all critical parts of the vessel to talk to each other. In our world, that was primarily between the pilothouse set (Tom Hanks’ domain) and the CIC set (command center for radar and course plotting during engagement). In real life, these areas are several decks apart, in the movie world, the pilothouse was on a twelve-foot-high gimbal with the ten-foot-high set built on top, which could articiulate more than thirty degrees in any direction (to simulate big seas), truly a marvelous thing to see in motion. The CIC set was built on the stage floor some fifty feet away from the gimbal.

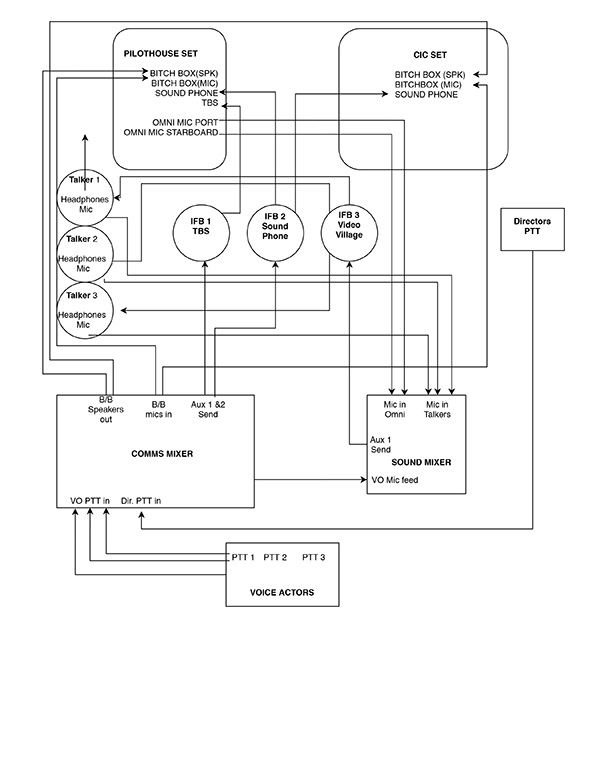

The Director wanted to shoot both sets at once and record both sides of the action. The interaction between the actors would be via both the Bitch-Box and the “Sound Phone.”

The Bitch-Box was a two-way communicator with a speaker for broadcast and a microphone on a push-to-talk switch, which would cut out the speaker and activate the internal microphone. None of the units we had actually worked and most were just shells with a ratty 1940’s speakers rotting away in them. The best solution I came up with was to make this communicator open so that one set could hear the action in the other as we were shooting simultaneously. My option was to install a tiny self-powered monitor in all the boxes and place an Omni-directional conference table-style mic close by to serve as a signal to replace the PTT mic. All the mics and speakers were hardwired from the gimbal via a multichannel stage box (giving us only one major cable to wrangle and protect against the gimbal movement) back to a dedicated Communications Mixer (with its own operator) to mute and open the speaker/mic channels as required. The mics themselves were given to the set painters and painted the exact same color as all the other wires, conduit, and set walls so they literally disappeared in plain sight. In fact, all of our cables some five hundred feet in all were painted so that we could wire the set as needed.

Next was the “Sound Phone” as the Navy calls it. This was very similar to the Bitch-Box except it is a private one-to-one connection handset for the captain to talk to the various departments. Again, all 1940’s equipment.

I decided that the preferred solution for this issue would be to rewire the insides of the phones and send the production audio from the actors directly to the earpiece. I took apart the phones removing the voice module and reinstalling a working headphone driver from some old 7506’s, wired in the driver, ran cable through the handset down to a one-eighth-inch jack so I could plug it into an IFB which could be hidden on set. Now I could route the signals I wanted to whichever phone was needed. This required however, a discreet IFB channel dedicated to “Sound Phone.”

The third major equipment used by the Captain (Hanks) on the bridge (pilothouse) was a ship-to-ship radio telephone referred to as the TBS (Talk Between Ships). This allowed the Captain of the convoy to talk directly to the other ships in the convoy so as to help keep the convoy together on this dangerous Atlantic crossing. As our Director wanted these conversations to be live rather than have a script supervisor read the lines, the TBS also had to be fully functional.

The TBS is a unique piece of equipment with a unique look and was very hard to source. Any mods would have to be very carefully done so as to not upset the Production Designer and Set Decorators! Again, I must take time to thank all those that helped me get access and were patient as I took the equipment apart to figure out the best way to make it work for our film needs. It was not possible to replace any of the phone cords and as the unit was totally full of non-working parts, anything I did needed to be remote from the TBS itself. Testing the connections within the unit and the handset, I used the existing 1940’s wiring to connect a replacement headphone driver, then added a discreet cable coming through the set wall to another IFB (another channel). The signal sent to the TBS was going to be from voice actors, off screen and off gimbal, so I set up a VO station close to my Comms Mixer with up to three “push to talk” handheld PA-style mics. This would ensure no unwanted signals when not in use or any cross talk if more than one actor was playing the various convoy ship roles.

The most difficult modification I undertook was that of the “Talker” equipment. Anyone who has seen a period Navy film would recognize the device that looks like a switchboard operator’s mouthpiece worn around the neck and a pair of old school headphones. This device allows any “Talker” to move around the ship plugging in where required and transmitting the orders from the Captain or receiving information from all different parts of the ship. This unit had to function in a duplex style as the script called for multiple overlaps of info coming over the headphones and orders going out via the mouthpiece, as would be the case in a battle scenario.

Again, however, these had to remain period and look unaltered. They would be front and center on camera as they were worn by some of our principal actors. Oh, yes, one more thing: the Talkers operate both inside and outside of the ship so they would be getting soaking wet from the special F/X water sprayers, Ritter fans, and misters.

After taking them apart and drilling access holes, I wired a Countryman B6 in each mouthpiece, added a ton of acoustic foam for wind protection, wired new headphone drivers, sourced some old-looking cable to replace the existing and created an exit for my signal cables at the chest harness so that each actor could wear a transmitter for the mic and an IFB for the headphones. These IFB’s received the same mix as the director/producer so that the actors were aware of their place in the scene and luckily, the 1940’s headphone pads still cut out a lot of background noise from our SFX equipment.

The sonar operator had another set of headphones that were sourced from an old aviation store and luckily they worked, so I only had to modify the plug for an IFB. The sonar room also had a Bitch-Box and a dedicated Omni mic.

I placed more painted Omni mics hardwired into the pilothouse at the entrance and exits as it was such a tight set a boom could never get into those spots. Movable plants were used in many locations depending on the scene. Actors were wired in their helmets during battle stations and on their clothing when not.

Betsy, my Boom Operator, spent most of the show on an ENG pole with a Neumann KM185 as the pilothouse was so tight (a Schoeps CMC couldn’t handle the moisture), and when not in the pilothouse, she was getting soaking wet using a Sanken CS3E with full Rycote zeppelin with sock, windjammer, and rain-man on the fly bridge.

We played a lot of sound FX throughout the shoot (many different gunfire sounds, airplanes, sonar pings, etc.). Some were from editorial but most were sourced from free FX libraries and I modified them on the fly for pitch, speed, volume, and multiple sample layering for loudness. This was done with Steinberg’s Wave lab and they were cranked through my 2k watt six-speaker system mounted all around the ship.

I treated the workflow like a mashup of production audio and live sound applications. I gave multiple feeds to multiple IFB channels, sent production audio to the Comms Mixer, received ISO channels back from the comms for recording and to feed into the dailies, and played the sound FX live. I used two Sound Devices 788t recorders, (timecode and sample rate locked), the first as a dedicated production audio recorder, the second recording the hardwired Omni mics, the handheld voice actors mics and the sound FX scratch track for reference.

One unforeseen advantage to all of these channels of audio and discreet feeds was that the Director was also given a PTT mic that we could route into any set or any Bitch-Box or phone or even into the headphones of the Talker all of which was invaluable as the communication when all the Special FX, gimbal, and Sound FX were going was somewhat difficult.

It was a very ambitious project and required a lot of forethought, but once dialed in, it went very smoothly. Thanks to the producers’ and director’s desire and my crew’s great work.