Behind the Video Avatar: The Way of Water

by Dan Moore

Being a Video Engineer can be a lonely position on set. On occasion, like a Script Supervisor, you can convince production that additional help is needed because of added cameras, multiple location moves, or cameras that will leapfrog from set to set. Having more support is often the exception and not the rule. However, on Avatar: The Way of Water, with four and sometimes five stages in operation at Manhattan Beach Studios (MBS), quite often three to five operators were employed with some days reaching as many as eleven. With complicated setups and prepping upcoming scenes, planning and coordinating personnel was essential in making this project a success. This started in 2005, when the technical planning and pipeline development began for the first Avatar film.

The pipeline is the process by which all departments contribute their specific function to a main storage center, which then disseminates and organizes large volumes of information. The information being ‘bits of data.’ These digital files are cleaned up and sent to the visual effects house and other departments to use. In 2005, many were responsible for the development of the pipeline, including members from Local 695. Glenn Derry was a principal developer, supported by Gary Martinez and Mike Davis. Both had the creative talent, the engineering expertise, and field experience to build a pipeline that worked. Later in 2012, Ryan Champney, the Virtual Production Supervisor at Lightstorm Entertainment, continued to improve and streamline this pipeline. He was able to make rapid changes to the overall system and personalize it for different departments. For example, writing custom software for the automated publishing and metadata tagging of the audio, video, facial, and performance-capture datasets. This overwhelming task resided with these principal technicians, whose degrees in computer science, electrical, and mechanical engineering supported the groundbreaking work. I enjoyed observing and learning from skilled engineers overcoming complex challenges for this project.

To walk onto the set of Avatar would be deceiving and underwhelming because of its warehouse-like appearance. This is not a traditional film set like those constructed by carpenters, painters, and set designers, to then be populated later with stylized lighting and filmed with traditional cameras.

On one side of the stage are two raised platforms, which look like old-style TV phone banks. In this case, the phones and staff are replaced with computer workstations and technicians. Each station is responsible for different aspects of the show. These raised platforms, called the Brain Bar, are workstations for head rigs, QTAKE, RealTime, take assets, script, stunts, and the Editorial Department.

Brain Bar. Photo by Mark Fellman –

20th Century Studios

On Stage 27, in front of the Brain Bar, was the Volume that measured 120’ x 75’. The Volume is where the action sequences were recorded. The Volume was surrounded by one hundred eighty infrared cameras, suspended from the ceiling, casting IR light over the entire defined space. These cameras, which are calibrated for accuracy every morning, track the actors’ movements within the Volume. It also tracks a ‘virtual camera’ and the props for those action sequences. The actors wore black suits with reflective spherical markers on them that the IR cameras followed. When looking at a RealTime monitor of the Volume, the performers and the characters they were playing could be seen walking around in a 3-D field. The virtual camera, which put a frame and lens around the image, provided the visual background, creating the location and characters for the scene. On each stage, four 65” OLED monitors were placed around the Volume, and thirty smaller monitors at each workstation, showing the Avatar facial and body movements, as well as the scenery of this imaginative world. Instantaneously, the scene became a close approximation of what it would look like in the theater. Not photo-realistic, but close.

Additionally, within this crowded Volume, up to sixteen live Sony cameras were positioned to capture close-ups of the actors’ facial expressions and movements. This allowed the director to see the detailed performances of the actors and know what takes ‘to circle.’ These directors’ video notes of the articulation of the actors’ expressions helped to make references for final photo-realistic digital images done later. These movements, along with sound and video, were all digitally recorded in a massive, air-conditioned server room that accommodated several petabytes of storage.

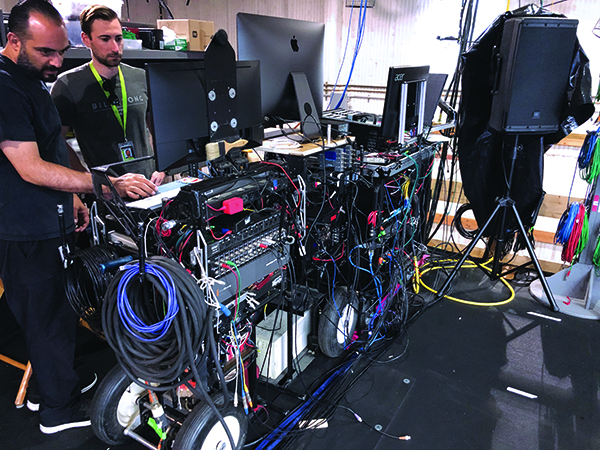

Where does the Video Assist Operator fit into a project like Avatar? My primary function was to record the virtual image along with a 16-camera matrix that would be displayed on the monitors. The recording stations became stationary after hundreds of miles of Canare Belden BNC, and fiber-optic cable were laid to create the pathways. Hardware equipment from Evertz, Blackmagic Design, Decimator Design, Panasonic, and Sony were used in the build-out. Much of the equipment was sourced from B&H Photo and Adorama Camera. Production did source equipment locally, as well through Band Pro Film & Digital in Burbank. Air-conditioning, backup power supplies, and racks of digital storage units were in place before the first day of filming. In addition to the build-out, solar panels were placed on top of all stages, to cut down on the electric bill and all water used in the film tanks were delivered to the golf course right next to the MBS stages.

On the first Avatar film in 2005, the production used video assist Playback Technology devices to record the virtual camera and three-quarter-inch tape decks to record the live-action cameras. In 2015, Avatar: The Way of Water production used the QTAKE system to record the virtual camera and a matrix of the sixteen live cameras. In addition, the individual live cameras were recorded on AJA recorders and uploaded onto the digital server after each take. The matrix image for the video assist came from a Blackmagic MultiView 16 device. As a criteria, all devices had to have the capability to be remotely software controlled so that the media was properly named and published on roll and cut.

The Video Assist Operator was also responsible for troubleshooting and the overall reliability of the pipeline. Making sure that the sixteen live-action cameras, head rigs, and other departments had proper timecode, as well as tri-level sync and other reference outputs. All the workstations, about twenty in total, each had a monitor for live and playback images. The Video Assist Operator was also responsible for transmitting the images to the QTAKE workstations and to the Camera Department monitors for focus.

In June 2016, I was employed once again on Avatar to head and coordinate the Video Department. The build-out of the pipeline was almost complete. I assisted both Ryan and Gary to help finish and get ready to film Avatar 2 and 3. At this point, I needed to assemble a group of Video Engineers who would be able to work on this project at various times. I scheduled personnel who were able to commit to the show and maintain their own client base. I knew a few operators but needed to find more. Within a few weeks, I was able to assemble twenty-five video operators that I could schedule at any given time. As the show progressed, the Director and Virtual Camera Operators would sometimes have a preference and would want to be paired with Video Assist Operators who were suited for them. The operators came from all different backgrounds, which included features, commercials, and live TV. Their technical ability varied as well. From basic QTAKE functions to a variety of problem-solving issues, every day had different challenges. Some operators expressed that the pressure of working with the director would be too tense. In this case, the Director was James Cameron. For Mr. Cameron, you need to be always ‘on,’ anticipate what he might need, and be able to technically answer his questions. Like Mr. Spielberg, he demands an A team of professionals. Surprisingly, Video Operators that came from live TV were able to handle the most stress in terms of personalities and technical issues. In the end, our Local was able to provide the most experienced and proficient technicians.

All the Video Assist Operators were able to bring their talents to this otherworldly film. I would like to congratulate the following operators, and their contributions to the success of Avatar: The Way of Water.

Shahrouz (Shawn) Nooshinfar: From Tehran, Iran, Shawn had been employed by several Persian and Armenian broadcast channels serving as an Uplink Engineer and Technical Director. He is also fluent in Farsi, German, and English, making him in demand at other international broadcast stations. He was brought on Anchorman 2 as a Technical Advisor and Engineer in 2011 and joined the union in 2012. He has worked as the lead media server and LED Engineer on Dr. Phil and other live TV events. On Avatar, he handled the biggest technical challenges with ease and confidence. He is one of the principal owners of Lightning LED, which specializes in video walls, media servers, and video assist. His company is a QTAKE distributor and technical support center.

Jeb Johenning: From Lexington, VA, was employed by Strata Flotation in 1988 and was responsible for the in-house video productions of their product, which was being distributed nationally. He also served as an Industrial Designer and had twelve US patents on different products he designed. Jeb has been a Local 695 member since 1994 and established his company Ocean Video in 1993. His company is one of the few companies that is a worldwide premier agent/dealer for the QTAKE system, which builds carts and provides technical support. His role on Avatar was more behind the scenes, providing support and perfecting the build-out of QTAKE streaming. This allowed all five stages to be interconnected and view takes filmed on different stages. This was a secure and quick way for the director to comment on the work of others.

Dan Moore: From Chicago, IL, graduated from college in 1983, and trained as a Video Assist Operator with Cogswell Video Services in 1984, one of the first video assist companies. Steve Cogswell trained many Video Assist Operators and made an impact on how video assist is used on set today that includes a sense of organization and the consistent use of quality equipment. Besides managing the operations on the set of Avatar, Dan worked with Ryan Champney in setting up and dismantling the video infrastructure for all the performance-capture volumes. All cables used for video, timecode, tri-level sync, word clock, data, and even the cable’s length had to be color-coded and incorporated onto the stages. With thousands of connections going in so many directions, this made the ability to problem solve much easier. Dan is currently the owner of Video Hawks LLC.

Eduardo Eguia: From San Luis Potosi, Mexico, moved to Mexico City in 1995 to work at the Broadcast Televisa Studios as an Editor and Post-production Engineer. He moved to the US in 1998 and in 2010 joined the union. Working as a Video Operator on Avatar, Eduardo was also responsible for building the QTAKE systems and other recording and editorial carts for the 3-story tank on Stage 18 at Manhattan Beach Studios, as well as all the carts for New Zealand. This turned into a blessing for production, since once the carts were completed, COVID shut down the Los Angeles operations which later resumed in New Zealand with the carts that Eduardo built. With the help of Roly Arenas, Storm Flejter, Ernesto Joven, and Peter Joyce, a total of twenty carts were assembled and used in production.

Roly Arenas: From Havana, Cuba, graduated from the University of Computer Science Havana as a Software Engineer. He worked in Havana as Graphic Artist and Video Engineer at Canal Havana Broadcast Studios and moved to the United States in 2010. He was hired as an Editor for the Caribbean Broadcasting Company in 2016 and joined the union in 2018. He worked on Avatar building carts and working as a Video Assist Operator.

Mike Pickel: From Dallas, Texas, graduated from University of Texas, Austin, with a degree in film. The same year, he moved to Los Angeles to work at Paramount Pictures as a Production Assistant and then transferred to Michael Bay’s company, Propaganda Films. There he worked as a PA and then later as a Video Assist Operator on commercial projects. He became a union member in 1995. Sadly, Mike passed away from cancer in 2018 during the filming. He was one of the first Video Assist Operators to work on Avatar: The Way of Water when production commenced. His presence, humor, and talents were greatly missed.

So many other Video Engineers from our Local were involved and instrumental in making Avatar: The Way of Water a success. They include Andrew Rozendal, Alex Sethian, R. Scott Lawrence, Joe Kroll, Justin Geoffroy, Ben Betts, Peter Joyce, David Santos, Storm Flejter, Ernesto Joven, and several others. Our Local came through with skilled Video Assist Operators who worked together and challenged that singular often lonely position we all have been accustomed to performing, merging our creativity for a once-in-a-lifetime experience.