by Mark Agostino

When Production Sound Mixer Walt Martin called me to do playback on Jersey Boys, he and I assumed it was going to be just that, playback. Why would we think otherwise? This was how it had been done for decades. Well, we didn’t know it yet, but we were totally wrong.

There were weeks of emails and phone calls with the producers and Walt, and rumor after rumor about how we were going to shoot the musical scenes of the film. Finally, we had an answer. Clint Eastwood wanted to record everything live on set—all of the instruments and all of the vocals. He didn’t want to do pre-records. He wanted to get on set and actually shoot the guys performing in the moment. It sounded challenging. With my background in studio and live recording, I welcomed the challenge. Well, this challenge was going to be monstrous. It would be the most exciting and technically complex production work of my career.

It would have been less complicated if the actors sang and played their own instruments. If that were the case, we would simply set up some microphones for the vocals and drum kit, plug in a few direct boxes for the guitars and keyboard, put together a monitor mix so everyone could hear each other and start recording some takes. Unfortunately, the actors were only singers, not musicians, and one of them was neither. This was getting more complex. We were going to need offcamera musicians to play the instruments, bass, guitar, keyboard and drums, that the actors couldn’t play themselves. Most of the time we had an on-camera drummer and this added an additional challenge since we needed to mic the entire kit and none of the microphones could be visible. Let’s just say, it was rarely the same thing twice. Many times we were informed which musicians were being used themorning- of. Fun!

After a few meetings with the Producers, Walt and the 1st AD, David M. Bernstein, determined that we were going to need three things:

First, in order to give Post-Production the most flexibility, we needed to individually rig microphones for all of the instruments and vocals and record them to discreet tracks.

Second, after the performances were shot from the front, and, to allow the actors to save their voices, we needed the ability to quickly play back a good sounding mix of any of the previously recorded takes once the cameras had turned around to shoot the audience. The faster this could happen, the better. I had heard stories about the efficiency and speed of Clint’s shoots, and was told by the producers and 1st AD that he moved fast. They weren’t kidding!

Third, since we were going to have off-camera performers and oncamera performers, everybody needed to be able to hear themselves and each other. We would need a headphone mix for the off-camera performers and a separate foldback monitor mix for the on-camera performers.

One of the major obstacles doing a live recording is controlling the amount of unavoidable leakage from the foldback monitors into the stage microphones. This would have to be minimized as much as possible. I made sure the producers were totally aware of this from the start. They completely understood and were prepared to replace things in Post if need be.

With all of this in mind, I devised a plan that basically (and luckily) held true to form throughout the shoot.

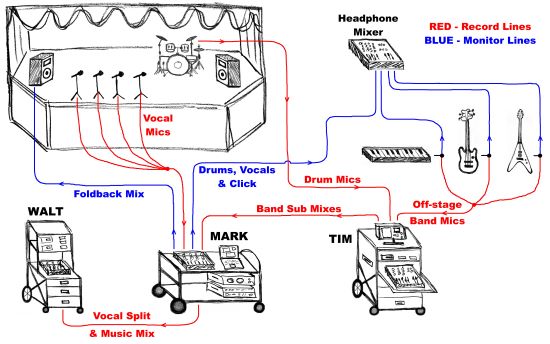

We were going to need two multitrack recording systems on set at all times. The first would be specifically used for recording the bands. The second (which I was going to operate) would record, on up to no more than eight tracks, submixes of the band from the first system and, at the same time, all of the vocal microphones. This would allow me, with a more consolidated session, to switch from recording mode to playback mode, do a quick mix and be ready for playback as soon as the cameras had turned around to shoot the audience. On top of that, since I then had all of the musical elements at my disposal, I could route whatever was needed to either the headphone or on-stage monitoring systems.

I soon realized that this project was going to be a huge technical undertaking. It was going to require live recording, sound reinforcement, music mixing and music playback. I could do all of these things myself, but there was no way that I could do all of these things by myself at the same time.

For the first time in my 18-year career in music playback, I needed a crew. With the immediate and full support of the producers, I began my search.

I needed someone to run the first recording system and focus specifically on mic’ing and recording all the instruments, someone who had studio and live music recording experience, someone who would take control and make decisions without me having to hold their hand. (I was going to have a huge amount of work myself.) I needed someone who knew how to do it all low profile. Those people who wanted to bring in a recording studio in a semi-truck just wouldn’t do; this person had to have a small footprint and be mobile. Looking for someone with the rare compliment of skills this job would require, two people came immediately to mind, but neither of them were in the industry anymore. I gave it a shot anyway. To my delight, one of them was all in. Tim Boot became my first crew member and he would turn out to be phenomenal, as I had expected. Next, we needed someone to primarily assist Tim with mic’ing all of the instruments each and every day, making sure the off-camera musicians had all the elements they needed for their headphone mixes, handing out earwigs, and other less-than-glamorous tasks. We needed someone to hold it all together, someone to keep us out of trouble. Along came Cristina Meyer. She too was phenomenal and truly invaluable to both Tim and me throughout the shoot. In fact, on Day One, even though Tim and I had only been working with her for a few hours, she was doing such an incredible job that we convinced her to ditch a scheduled gig so she could stay with us for the entire Jersey Boys shoot. What a relief!

Now that we had a team, I was excited to get to it. It was definitely the largest sound/music department I had ever worked in. On the regular music days, the combined department consisted of six people (three sound personnel and three music personnel). However, we had eight sound/music people working together on the really complex music days. . There were a few days I specifically recall from the shoot because of their complexity or it was a completely new experience or the amount of work we did in one day was greater than what I had done in an entire week on other shows. Let me tell you about a couple of them.

Day One: For some reason, I always remember the first day of a show. I remember this first day in particular because I got to meet Clint as we were setting up. (That was cool. He was cool.)

The location was a bar. There were four singers and a drummer on a very small stage. In an adjacent room, Tim and I had our systems set up. Tim used Boom Recorder on a Mac Mini and I used a Pro Tools HD Native Thunderbolt system on my Macbook Pro. Beside us were the guitar, bass and keyboard players. All of these off-camera instruments went through direct boxes. This gave us very clean recordings and created no extraneous sound on stage (above the foldback mix) to interfere with the acoustic recording.

To mic the drums, Tim used this wonderful set of miniature DPA microphones. He and Cristina developed a fantastic system of attaching the microphones to the rims (or sometimes the shells) of the drums and to the cymbal stands away from camera so they wouldn’t be seen.

For off-camera monitoring, we set up a small mixer near the offcamera musicians so that they could adjust their own headphone mix. The outputs of their direct boxes were split. One output went to Tim’s console to be recorded and the other output fed the headphone mixer. Since Tim was feeding me submixes of all of the instruments, I then routed whatever instruments were on stage (in this case the drums) to additional channels on the headphone mixer so the offcamera players could also hear the on-stage musicians.

The vocal microphones were another challenge. Since the time period of this film ranged from the ’50s into the ’90s, Props was going to have some pretty old microphones for several of the performances. Walt and I went through as many microphones as we could before we started shooting. Luckily, many of them worked well and sounded pretty damn good for being so old. There were a few, however, that were completely unusable for recording purposes. In these cases, Gail Carroll-Coe and Randy Johnson of the Sound Department did a fabulous job of attaching lavalier microphones to the faces of the old microphones, with great results. Then, since we did playback when the cameras went on stage to shoot the audience, the lavaliers would not be needed anymore and we removed them.

All of the vocal microphones were split at my cart. One set of outputs went to Walt for recording and I recorded a second set. I also sent a mix of the vocal microphones to an additional channel on the offcamera headphone mixer so those guys could hear the vocalists.

Finally, I hid a few speakers on stage so the performers there could hear their vocals and, most importantly, the off-camera instruments. That tied it all together.

As you can imagine, we had a pretty extensive setup each day. I initially asked for three hours and wasn’t sure even that would be enough. We weren’t just setting up a simple multitrack live recording, we were setting up a dual system multitrack recording session linked between two different rooms with a headphone monitoring system in one and a completely independent foldback system in the other. We just made it on Day One. Of course, we became more and more proficient with our setup as the show progressed. I think we may have cut the setup time down to an hour by the middle of the shoot. We had the process dialed in.

The most important thing was that the actors could hear everything they needed to hear in order to give their best performances. We had to provide whatever they needed to feel comfortable on stage.

Eventually, our setup was complete, and we did our first shot of the show. It was the songs “Apple of My Eye” and “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love.” We were all pleased that it went well and I must say, I was certainly a little relieved.

As we went along, there were, of course, minor adjustments/additions to the initial system design. The musicians that were hired were absolute professionals, but the first few performances were recorded completely free-time. No click (metronome) was used. Clint made it clear in the beginning that there was to be no click track. We weren’t even allowed to say the “c” word on set. The drummer was amazing. He truly kept as solid a tempo as anyone could. However, in order to help in the editing process, the producers wanted to be sure that the tempo did not slip between takes. As a result, we began sending a click to an earwig for the drummer. It was also fed to the off-camera musicians to keep everyone in time. The only problem that arose here was the drummer’s inability to hear the click through the tiny earwig. As anyone who’s ever used earwigs knows, they are best for hearing cues when the rest of the environment is relatively quiet. With the noise created by the drummer actually playing and the foldback speakers putting out a decent amount of level, it was understandably rather difficult to hear the click through the little earwig. Many times we had to give him one for each ear. This wasn’t a problem because there was hardly ever a close-up of the drummer.

As I’ve already said, it was rarely the same thing twice. Musicians were constantly being added to the ensemble the-morning-of just prior to shooting. Sometimes they were off-camera, other times they were to be on-camera. We learned to expect and be prepared for anything, and being prepared simply meant being prepared to change.

There were certainly many other notable days on the shoot. A few of them occurred during what the 1st AD called Hell Week. Ha! That was an understatement.

During this week there were going to be three absolutely crazy days. Two of those days, each at a different location, would have multiple performance areas, and one day would have a single performance at each of two different locations. Yup, one day we were going to have performances at two different locations. WHAT? It takes us close to three hours to put together our basic setup. How are we going to have time to break that down, pack up, move everything, load into the next location, and set it all back up again? Not only that, this particular day was to begin at one location with our basic four-piece band/four-vocalist setup for “My Boyfriend’s Back” and “Walk Like a Man.” Then, we had a company move to a location where we were going to shoot a twenty-piece big band performance of “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You.” Were we going to have another three hours to set up at the second location? I thought, we are going to need a bit more than three hours for THAT setup. We would later be informed that, in addition to the twenty-piece big band, there would be a separate three-piece off-camera band at the same time. YIKES!! That day was going to be huge.

Our saving grace was that we weren’t shooting the day before. It was a holiday, and we were able to pre-rig the second location as much as possible. This meant setting up Tim’s gigantic Yamaha DM 2000 console, plugging in and testing over 40 microphones (which then had to be disconnected because the set wasn’t finished), and putting up some extra speakers and amps I luckily had that wouldn’t be needed at the first location.

The plan was for Tim to immediately break down at the first location as soon as we entered playback mode and get any gear he needed over to the second location as fast as possible. I think we actually had Cristina transport a few of Tim’s things over there during the first part of the day when they were no longer needed at the first location. Cristina would follow him and they would begin reconnecting the big band microphones, setting up the off-camera band microphones and headphone system, and preparing everything they could before the rest of the company arrived. I was left behind to do playback for our final shots of the audience.

As soon as we were finished at the first location, I packed up and moved my gear over to the next one as quickly as possible. Tim and Cristina were flying through the setup. I dove full on into connecting my system to Tim’s, verifying signal flow from his console to mine, and making sure that the on-stage foldback system was happy. I happened to glance around and was amazed at how much gear we had at that location … and on the show itself. I remember having to pull something out of my garage in the middle of the project and thinking to myself how empty it looked. By that time, I had brought in just about every piece of gear I owned, and we used every bit of it at one point or another.

We were moving right along. Tim was going to be recording 48 tracks, so I quickly filled up and surpassed my self-allotted eight-track band submix limit for playback. Happily, there was only one vocal microphone.

Once again, we had barely finished our setup when the 1st AD called for the first rehearsal. There was so much equipment, so many microphones, so many cable runs, electrons flowing and neurons firing. When I think about it sometimes, with all of the thousands of components and interconnections, I am amazed and relieved when it all just works.

We eventually started shooting and everything went as smoothly as on Day One. It was really exciting to be involved in such a grand production. I felt proud to have been chosen to be a part of it.

As it would happen though, I had been so busy that I didn’t fully absorb the spectacular musical creation that had just taken place. Only after we had entirely finished the live recording segment of that location did it begin to sink in. It was time to go into playback mode and put together a nice mix for everyone to listen to while we did shots of the audience. I finally had a chance to breathe and something happened: I was now actually listening to the full mix of the performance. I wasn’t zoning in and soloing individual microphones to make sure the signal was clean. I wasn’t monitoring recording levels to be sure there weren’t any overloads. I wasn’t riding the vocal channel to be sure “Frankie’s” vocal level was consistent for him in the foldback speakers. I was now listening to over 20 musicians playing as one with “Frankie Valli” singing his heart out, and it sounded incredible. I was only listening in mono through a four-inch monitor on my cart, but it truly sounded amazing. When we did the first playback on the big speakers, I literally got goose bumps. The dynamics of the band, the smoothness of “Frankie’s” voice, the energy of all those involved was absolutely thrilling. All through my career there have been moments like this that have brought forth powerful and electrifying emotions I’ve never felt in any other line of work. To experience feelings like these on the job is my definition of success. As I had done so many times before, I thought to myself … there is, without a doubt, nothing else I’d rather be doing.

That day was the most exhilarating and, at the same time, most technically challenging movie-making experience of my career. Tim and Cristina did an exceptional job and would continue to excel throughout the rest of the shoot. I couldn’t have found a better team and can’t thank them enough. It was an absolute pleasure working with Walt and his team. They were always willing to lend a hand if we needed it.

In the end, it really felt great to have accomplished all that we did. To my knowledge, what we had done had never been done before. I am so thankful to Walt Martin, the producers, and Clint Eastwood for allowing me to join them in such an extraordinary adventure. As I was packing up on the last day, the producer, Rob Lorenz, said to me, “Thanks, Mark. Thanks for making it work.” That meant a lot.