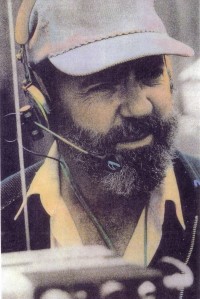

Jim Webb: A Profile

by David Waelder

“ He was the most perfect Sound Mixer I ever worked with.”

–Chris McLaughlin

“ I would say that Jim was the father of multi-track. I really would.”

–Harrison “Duke” Marsh

“ He seemed to field a lot of curveballs very elegantly.”

–Robert Schaper

“ He was a great educational source to learn from.”

–James Eric

“ Jim Webb is a crusty old pirate of a man who has a heart bigger than words can describe.”

–Mark Ulano, CAS

James E. Webb Jr. is justifiably renowned for his work developing multi-track recording on a series of films for Robert Altman. He captured the dialog from multiple cast members and interlocking story lines on such iconic films as Nashville, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, 3 Women, and A Wedding. He pioneered the multi-track process.

James E. Webb Jr. is justifiably renowned for his work developing multi-track recording on a series of films for Robert Altman. He captured the dialog from multiple cast members and interlocking story lines on such iconic films as Nashville, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, 3 Women, and A Wedding. He pioneered the multi-track process.

The scenes were so complex, so intricate and so audacious that Altman himself parodied the style in The Player.

And yet, this was really just the beginning of Jim Webb’s career.

He studied film in college, first at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and later at USC in the Department of Cinema. In 1962, he was drafted into the Army and, after training in radio and as a radio teletype operator (RTTY), served in Germany at an Army Aviation Repair Company that occupied the old Luftwaffe hangars on the military side of Stuttgart’s main airport.

Discharged in 1964, he worked for about a year at USC and then took a job, first at KTLA and then at the CBS station KNXT. The stations had contracts with IATSE and he got his IA card at that time.

ROCK & ROLL

Work in feature films was the goal but opportunities were scarce for recent film school graduates and new members of the union with limited contacts and seniority. Seeking to create their own work opportunities, he formed an independent production company with Pierre Adidge, a friend from Northwestern, and Bob Abel.

The newly formed production company did music specials for PBS and also documentary concert features. The Joe Cocker film, Mad Dogs & Englishmen, was the first feature, followed by Soul to Soul (as a consultant) and Elvis on Tour. These projects taxed his technical skills to keep everything in sync and sensibly organized. He was well aware that Woodstock required a full year of work to get everything synced and worked strenuously to avoid a calamity of that sort. He insisted on shooting regular slates and on assigning one track on the eight-track recorder to a sync pulse. His commitment to good protocol was not always adhered to but his efforts were at least partially successful and the films were all released in a timely manner.

ROBERT ALTMAN AND MULTI-TRACK

His Army training and experience with radio mikes and multi-track music recording on concert films gave him a good foundation in skills needed to implement a production style that Robert Altman was developing. Traditionally, films had treated their subject matter as if they were stage plays seen with a camera. Close-ups and tracking shots provide changing perspective but the action unfolded as a linear narrative. Altman saw the world as a messy place where events didn’t always proceed in an orderly way. Sometimes everyone would speak at once. Sometimes, with multiple participants, it wouldn’t be clear who was driving the action until the event was over. He wanted to bring some of that messy uncertainty to his film projects.

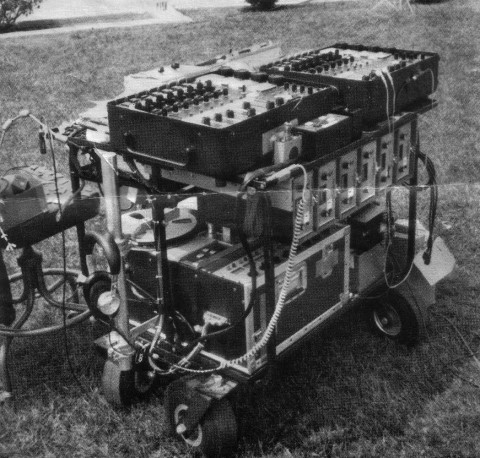

Altman used a loose and improvisational style in films like MASH but encountered difficulties with sound for McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Without precise cues to know when each character might speak, it was difficult for the Sound Mixer to deliver a suitable track, especially when action was staged in authentic locations with hard floors and other acoustically difficult features. Having multiple microphones, and assigning the outputs to isolated tracks, was the obvious solution. Altman brought in Jack Cashin to design a system of multi-track recording that might be used on location. Most of the equipment then available was designed for use in a studio and it required some ingenuity to adapt it for location use. But assembling the hardware is only part of the equation; someone must operate it effectively and this presented challenges to the Production Mixer.

The system Cashin developed used a Stevens one-inch, eight-track recorder. With one track assigned to a sync signal, seven tracks were available for discrete audio. No multi-track mixing panels that could work off DC were available at that time so 2 eight-input, four-output consoles were linked to supply the needed signal feed. The whole business ran off a 12-volt motorcycle battery with a converter circuit to provide the higher voltage needed by the recorder.

Paul Lohmann, Altman’s Director of Photography, recommended Jim Webb for the multi-track skills he had demonstrated on the concert films. And that was the beginning of collaboration among Robert Altman, Jack Cashin and Jim Webb on a series of films.

Jim Webb:

They had everything together but they didn’t have any idea about how to use it. And I said, “Well, the only thing that makes any sense is to put radio mikes on everybody.” You can’t have open mikes because if you add those back in the pre-dub, the background is going to be astronomical—you won’t be able to tell anything. You have to do a lot of close mic’ing to make this work. So my contribution was radio mikes.

The first picture made with this multi-track technique was California Split. It was a fortuitous choice because it made good use of improvisational technique but was less ambitious in that application than subsequent projects. It provided an opportunity to shake out the system.

By the time we got to Nashville, we pulled out all the stops and went blasting our way through it. We shot that film in eight weeks at a dead run.

Putting radio mikes on each performer and assigning them to discrete tracks was an obvious approach but there were also limitations. Post work required an additional two weeks to deal with all the different tracks. There was also an inherent lack of audio perspective. Jim Webb explains it best himself:

There’s no perspective. We ran into that immediately on Nashville. There’s this scene that opens the movie which is where they’re all in a recording studio and I went about putting radios on everybody, even the ones behind the recording glass. And I went over to Altman and I said, “Are you sure we’re doing this right? We’re throwing perspective just completely out the window.” And he said, “Yes, yes, of course we are.” I went back to putting radios on. About twenty minutes later, he comes over and says, “Are we doing this right?”

A little late to change the action now. And it worked out. I would have people come up to me and say, “That was the most realistic sound I’ve ever heard.” Well, there was nothing real about it. You’re not hearing people shooting through a double-plate glass and hearing all the conversation inside there, as well as what’s going on outside.

But it was primarily designed for overlapping dialog and improv and things of that nature where you never knew what anybody was going to say.

And you can’t possibly listen to it all because it’s just a Tower of Babel. So once I previewed all the radios and made sure they were working, you were just watching the meters.

Capturing the dialog with individual radio microphones was a complex undertaking that required all of Jim Webb’s skill but it accomplished what Robert Altman needed to fulfill his vision for the film. According to the Supervising Sound Editor, only two lines weren’t recorded in the original production track. One was a failed radio on Henry Gibson and the other one was an added line of Allen Garfield’s back as he was walking away from us. That was it; the rest was all stuff that we did.

THE ULTRASTEREO MIXER

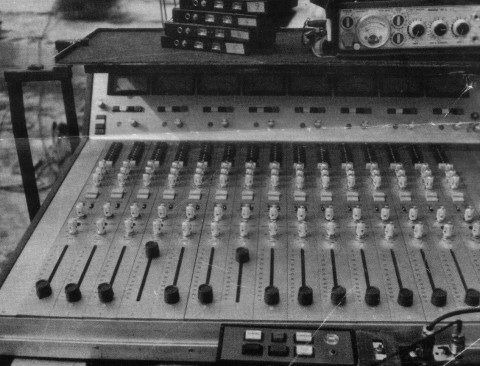

Very little was available in the way of a portable mixing panel at the time Jim Webb was working the multi-track pictures with Robert Altman. The specialty mixing panels that Jack Cashin adapted for those pictures had liabilities that make them cumbersome for use on most pictures. He and Jack Cashin set to work to address this need with a capable mixer.

In the late to mid-fifties, [Perfectone] had a little threepot black mixer that was very popular in the studios; it was a little rotary pot thing and everybody used it. And it was around a lot. And then they updated their little portable mixer with a straight line. And they had six in and one out—it was still a mono mixer. And I liked the straight-line faders because you could handle them a lot easier than trying to wrangle three rotary, four, five rotary pots. So I said to Jack [Cashin], “Can we modify this and make it two track?” And we looked it over and said, no, it’s going to be simpler to make our own version of this. And he designed it and I built it. I built a dozen of them, maybe 12 to 14 of them. Sold them all.

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN AND A RETURN TO BOOMING

Right after Nashville, Jim Webb was hired to do All the President’s Men, largely because his multi-track skills were applicable to situations where actors might have to interact with video monitors playing in the newsroom. He was also particularly skilled at recording telephone conversations and there were many of those in the script. Although he had his own working prop phones, the Special Effects Department supplied the multi-line key phones used in All the President’s Men. Webb provided a phone tap to record the phoneline conversations on a separate track from the on-camera dialog. He would supply an audio feed to actors brought in just for their off-screen dialog. Because everyone heard everyone else, either through the phones or via a specially provided feed from the mixing panel, overlaps were possible and could be recorded naturally. It was expensive because of the need to bring in actors who didn’t appear on screen but freedom from the pace-killing process of having lines read by a script supervisor allowed the filming to fly and yielded more natural performances.

When we rehearsed it, it went like lightening. And when we got through, Bob [Redford] said, Holy cow! … He was shocked at how fast it went and that’s how we did the scene.

It’s not often that the Mixer gets a chance to dabble in how the scene plays.

All the President’s Men was more tightly scripted and allowed a more normal recording technique than the Altman pictures. It came at a good time:

I remember going into an interview one time and I said, “I’ve done this Altman this and that.” And the guy looks at me and says, “OK. What else have you done besides that?” And I didn’t have anything so I was thinking to myself, it’s better to work around; it’s better to do different formats and utilize them when you need them.

Chris McLaughlin was his Boom Operator on the film but the newsroom scenes presented particular challenges. The Washington Post set was gigantic, consuming two linked stages, and lit naturalistically from overhead fluorescent lights. Fortunately, due to the heat they generated, the ballasts for all those lights were mounted in a shed outside the stage so there wasn’t a serious problem with hum. Director of Photography Gordon Willis favored up-angle shots that showed all the lights in the ceiling. When Jim Webb asked if it would be OK to boom, Willis held out his hand, casting multiple soft shadows and said, “I don’t care what you do as long as you don’t make any shadows on my set.” “That was the end of that conversation,” says Webb. Chris did manage to boom the picture using primarily a Sennheiser MKH 815 from below, flitting in and out of the performer’s legs.

According to Chris McLaughlin, Webb entrusted the microphone selection to his Boom Operators. But the big Sennheiser was clearly a favorite. He describes using one on The Long Riders. The Keach brothers were fitted with wireless mikes when Jim Webb learned that they intended to ride into the Chattahoochee River at the conclusion of the dialog. Concerned about immersing the radio packs in the river, Webb resolved to boom the scene. Chris McLaughlin thought that he could capture the dialog with a Sennheiser 815 off a 10-foot ladder. He turned the mike back for maximum rejection of the sound of the river and they accomplished the shot. At the end, the Keach brothers did ride into the river and Webb didn’t lose any mikes. “So I have a lot of respect for the 815,” he said, “it got me through a lot of tough places.”

It’s key to an understanding of technique that there was no agenda, no rules about how each scene needed to be recorded. Jim Webb approached each project with an eye to achieving the Director’s vision and capturing the elements needed for the picture as a whole. Duke Marsh says: “I think with Jim it was, if I’m [Post] mixing this thing, or I’m going to do the Post work on it, what do I want to hear?”

And Jim himself says, “You just gotta do what you gotta do, you know. And I never worried, pretty much at all, about what people thought about what I was doing. If I saw a way to do it and it felt right, that’s what I was going to do.”

Each project presented its own set of challenges to test his skills and preparation.Noises Off presented a particularly complex situation. Originally a stage play, it concerns an acting company rehearsing and presenting a play on an elaborate set. Come opening night, everything goes awry, cues are missed, props misplaced, and the comic errors pile one atop the other. The two-story set mirrored the set that would be on stage. To accommodate the perspective of the Stage Manager, a key character, the entire set was built ten feet above the sound studio floor, complicating any work from the stage. Peter Bogdanovich, the Director, intended to shoot the entire film using a Louma crane that had the ability to swoop in on individual performers, further complicating efforts to capture the audio with a boom microphone. Moreover, the script took the actors up and down stairs and through doors at a frenetic pace.

The actors hoped to avoid using radio mikes, in part because there was often little costume to conceal them. But they needn’t have worried as the pace and frequent costume changes made that an inconvenient choice.

The original plan was to distribute plant microphones throughout the set and go from mike to mike as the action required. After a rehearsal, Webb said, “Guys, I don’t know.”

McLaughlin thought he could capture the dialog using Fisher booms and had a plan for how to accomplish it. They would use two of the big Fisher booms and, to get them high enough to work the elevated set, they would replace the regular bases with purpose-built scaffolds and mount the booms to the top rails of the scaffolding. Wheels fitted to the scaffolding allowed moving the booms into position as needed.

Jim Webb was open to the idea and brought in Fisher booms with 29-foot arms fitted with Neumann KMH 82i microphones. Randy Johnson joined Chris to operate the second Fisher and Duke Marsh was brought in to work from the greenbeds with a fishpole to catch anything that fell between them. After hearing a rehearsal, Jim Webb said, “This is the way to go. Pull those plants.” They did use a few of the plants to pick up dialog occurring well upstage, under the set overhangs where the booms couldn’t penetrate, but using the big Fisher booms simplified the plan considerably. The plan still demanded considerable mixing skill to blend the two main booms, the fishpole operated by Duke and the occasional plant mike, but there was logic to the operation and the team successfully recorded all the dialog.

Other films presented challenges of their own. The Bette Midler films, The Rose and For the Boys, each presented playback challenges because of the large audiences or the complex shots envisioned by Mark Rydell, the Director. Webb worked with Re-recording Mixer Robert Schaper on For the Boys to build modern elements into period microphones so they might accomplish live-records at the highest quality levels. Robert Schaper recalls:

We ended up stealing vocals off of those mikes in the playback situations. One of Bette’s songs to her husband, when she is reunited with her husband, had a very silky, lovely, studio playback [of] “I’m Going to Love You Come Rain or Come Shine.” And she had a very silky rendition of that. [But] it didn’t match her acting performance at all because she was crying, overwhelmed with seeing her husband that she hadn’t seen in months and she was very worried about it and everything else. And we had planted … a Shure 55 with a rebuilt Shure capsule in it. Even with playback coming at her, the isolation was good enough on her actual live vocal—and she always actually sings all of her lip syncs. And she performed the heck out of the song … I ended up compiling all of that and using her live vocal—rather than the pre-record … from the plant that we had out there … and it turned out to be a really great acting performance.

CREW RELATIONS

“ He left a lot of it to the boom man. He walked on and said the boom man was the money-man, the boom man, he believed, controlled the set. ”

–Duke Marsh

“ He put great trust and faith in his Boom Operator. It was a collaborative effort. ”

–Chris McLaughlin

Over the course of a career, every Sound Mixer works with many Boom Operators, Utility Technicians, and Playback Operators. All who worked with Jim Webb praise his skills, his concentration, his commitment both to the project and his crew. A few brief stories from Duke Marsh illustrate:

[From Beaches] I would go and grab the snakes at wrap and he comes up behind me with gloves on and he said, “No, I do that.” “But I’m the cable guy; that’s a cable.” And, instantly we were buddies. And he’d go, “But, Duke, you gotta understand, those snakes are for me so I can work off the truck.” And in my whole career with him, in the rain, in the mud, in the snow, he’d always come off that truck. And there were days when I would say, “But you’re the Mixer.” “Well, you got other stuff to do. Go do that, come back, give me a hand.” That was Jim. He would always back his crew.

And then, in 2001 when he was receiving the CAS Lifetime Achievement Award:

I get a phone call and Jim says, “I want you to come. You’ll be at my table.” Well, he invited Doug Vaughn and Chris McLaughlin. [He delivered a speech accepting the award] then he says, “Those three guys at that table are responsible for a lot of this in my career. If it wasn’t for the boom man, putting that mike in the right spot, I wouldn’t be here.” And he had us stand up and we got an ovation. And I’m thinking, how many mixers pay attention to the guy that’s out front?

AWARDS AND ACHIEVEMENTS

In addition to the CAS Award, Jim Webb won the Academy Award for All the President’s Men in 1977 and the BAFTA Award for Nashville in 1976. He received one other Oscar nomination and three additional BAFTA nominations.

Nashville and All the President’s Men are each featured in both the Criterion Collection and the Smithsonian List. While Robert Altman and Alan Pakula, respectively, are recognized for their vision, Jim Webb shares in the accomplishment through his skill and inventiveness in facilitating that vision.

It’s also instructive to note the Producers and Directors he’s worked with multiple times. The list of three or more film collaborators includes Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Garry Marshall, Walter Hill, Bette Midler, and Paul Mazursky. Mark Rydell is one of several directors who employed him twice.

For each of these directors, Jim Webb contributed a sense of the role of sound as part of the whole and adjusted his technique to meet the needs of each particular project and the vision of that particular filmmaker. In talking with him, it is apparent that he has taken great pleasure in the process.

Jim Webb: “Good production sound has production value! Don’t give up. Be consistent and do the best you can.”

Mic’ing the Instruments

In the course of interviewing for this profile, Jim Webb shared many great stories that didn’t fit neatly into the narrative. This is one of the stories rescued from the trim bin.

In California Split, it started there and at the end of the scene there was going to be—and I found out this about two minutes before we were going to shoot it— there was a piano with tacked hammers in the bar and there was a lady that would play the piano and sing. Elliott Gould was going to be sitting there and they were going to talk a bit while she was playing the piano—and eventually they were going to sing “Bye Bye Blackbird.”

And I said, oh my God, it would be nice to know about this a little bit earlier. So I ran back and the only things I had around in those days were the old ECM-50s which were some of the first electrets from Sony. And I had a bunch of those. So I ran over to the piano, raised the lid and put one taped to the cross bar pointed down and the other one pointed up to the top end. I connected cables from the mixing panel, closed the lid, put a radio on each performer, ran back, turned the equalization all the way up – all I had – and prayed. So I laid down four tracks and it worked pretty well. In fact, they couldn’t duplicate it.

The scene didn’t really make the film but the song is in there, at the end, over the credits.

Anyway, they discovered that I could do that. So, in the smaller scenes in Nashville, where there were just the two gals singing in a place and the piano and whatever, I would do that mike, if it was an old upright, I would stick a couple of mikes in there … and as long as I hadn’t filled up the eight tracks, I could do that.

Well, they decided that I had so much dialog going on that I couldn’t cover all the music too; I just didn’t have enough tracks. So, they hired a guy named Johnny Rosen to come in and they had a sixteen-track truck and they hired him to do the Opryland stuff and all that. And their mixer, I think his name was Gene Eichelberger, was shadowing me just to see what I was doing. And he saw me doing this lavalier routine and I’m thinking to myself, I can’t tell anybody in Nashville that I’m using lavaliers to mike instruments because they’re going to laugh me out of town. Next thing I know when I get to Opryland, Eichelberger is over borrowing every ECM-50 I’ve got and he’s taping them to fiddles and everything in the orchestra he can find. So, I thought, well, OK, that’s how we’re going to do this. And that’s how it all kinda went down.

Interview Contributors

These colleagues of Jim Webb assisted in the preparation of this profile by making themselves available for interviews:

Crew Chamberlain was Webb’s Boom Operator on several films including The Milagro Beanfield War, Legal Eagles, and Down and Out in Beverly Hills.

James Eric knew Jim Webb from his days working the microphone bench at Location Sound. Later, he served as Utility Sound on Out to Sea.

Robert Janiger is a Sound Mixer and friend who collaborated on further development of the Ultrastereo mixer.

Harrison “Duke” Marsh worked with Jim Webb on seventeen films including Pretty Woman, For the Boys and Noises Off. He worked variously as Playback Operator, Utility Sound and Boom Operator.

Chris McLaughlin boomed twenty-one films for Jim Webb starting with California Split and continuing through Noises Off. Among others, he did Nashville, 3 Women, The Rose, The Long Riders, and Hammett.

Robert Schaper was Supervising Music Engineer on For the Boys.

Mark Ulano is an award-winning Sound Mixer who considers Jim Webb a mentor.