Notes From an A-2 at the Grammys

by Ric Teller

Quite a few years ago, I was working on a show with Murray Siegel in the days when Murray was still on the audio crew. During the show, or maybe it was during rehearsals, my memory is a bit fuzzy on the details, Walter Miller, the iconic director, got on the PL and told everyone that “the floor A-2 job was no career for a grown-up like Murray.” Working as an A-2 in television for more than thirty years, including more than half of the live televised Grammy Award ceremonies, I can tell you without question that Walter was absolutely right.

If you can’t act a bit like a kid, scoot around on the floor, laugh out loud, poke a little fun and have some poked back at you, dance a little, be enthralled by the presence of some music icons, and come out of it wanting more, this job may not be for you.

To be sure, there are challenges in doing the Grammys, not the least of which is that we are under a lot of pressure to perform our stage audio-ballet, or more aptly, a rugby scrum, in a timely manner. We try our best to make everyone happy, the artists, the Director, Production Staff and especially the rest of our amazing Sound Crew. The group of mixers and techs that bring each and every part of our production to the show that you hear on television are supremely talented engineers and more importantly, are very nice people. Together, we have had some true successes including a clean show in 2015 and along the way we have had a few bumps in the road. Our A-2 crew has been lauded in print as an example of audio excellence and after one tough year, derogatorily identified as members of the Santa Monica High School A/V Club. Go Vikings! In 2014, the Grammy road was decidedly bumpy. The dress rehearsal was a train wreck. There is a specific amount of time allotted for each of the 128 items in the show and the only time we do the band-to-band staging transitions in real time, is in dress. We were late on four or five changeovers, band carts arrived on stage slowly and we had several audio and instrument issues. I am not one who believes a ‘baddress’ means ‘good-show.’ I like it all to be good.

In the live show, if something doesn’t work, we quickly evaluate if the broken part of the setup will have a major impact. Let’s say, we are ten seconds away from a performance and the problem is Viola 3 or Snare 2 bottom, or anything else that won’t be noticeable to the viewing audience, we just let it go (damn that Viola 3 mic). If it is something more important, such as a vocal mic, a lead guitar or piano and it is not easily fixable, then we tell the Stage Manager, who tells the Head Stage Manager, who tells the Director and the Executive Producer and they decide the potential impact of a flawed performance. Sometimes they will try to give us a little more time to resolve the issue, a longer tape package and an extended acceptance speech. That twenty seconds or so might be enough time to make a game-saving difference.

It is late in the Grammy show and we are pitching a shutout. After our relaxing eighteen-minute meal break, we cleaned up the band risers, made sure the mics were in the correct positions and secretly replaced a critical problematic cable. All the issues from dress rehearsal seem to be resolved.

Band carts are flying up the ramp, The Highwaymen guitar rig is behaving, and Paul’s vocal in the Taylor Swift number is clean. It is item 108, Macklemore and Ryan Lewis with Trombone Shorty, and we are line checking.

Strings good, guitar good, vocals good, nine RF instrument mics all good. Choir 1 good, Choir 2 good, Choir 3 … not good.

Remember, we are in a live show, musicians are on stage and their performance is seconds away. I pivot and reach down to change the Choir 3 input from Pair 3 in our sub-box to Pair 7, then go to the main box and reach down for the cable on top, barely looking to see if it is the correct one. I know it will be, because Eddie McKarge, my partner on the B-stage, has been sending Pair 7 signals directly to the patch part of my brain. The connection is made, he casually checks the mic one last time and of course, it is good. Shutout preserved and maintained through the end of the show.

The Grammys are in the best way, a collaboration of more than sixty sound people led by our own audio coordinator … err … complicator … err … aggravator, Michael Abbott. Mike has worked on nearly thirty Grammy shows and is in charge of the audio details large and small that make everything work as smoothly as possible. He also runs interference when needed. Without Mike’s guidance, no one would know how RF #8 gets to the final mix. Really, how does it?

Staples Center is the home for three Los Angeles professional sports teams that are all in season during the Grammys, so our access to the venue is quite limited. We begin on the Tuesday, before the show by running thousands of feet of cable. Fortunately, much of the connectivity is done on fiber these days. That big copper stuff is way too heavy. Wednesday, we have an audio meeting to address the specifics of the show and then continue our setup. Rehearsals begin on Thursday and continue for three very busy days.

Finally Sunday arrives. First we rehearse anyone who we haven’t seen yet, next we do a full three-and-a-half-hour dress rehearsal, followed by a three-and-a-half-hour live show. We finish show day with four or five hours of wrapping cable and putting our toys away. It is a very long, fun day.

The broadcast this year was filled with a wide variety of performances. Two of my favorites were AC/DC, who opened the show in fine fashion, and Usher who did a lovely version of “If It’s Magic,” accompanied only by a harp until the last few bars when Stevie Wonder joined in. It was magic.

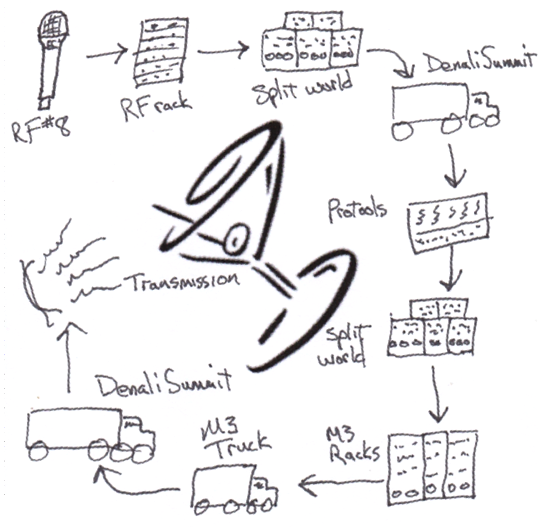

About that RF #8 question. It originates backstage in the RF rack and gets to the split world via a two-hundred-foot W4 cable. At split world, the RF goes into split C, Pair 8, which is split to the FOH and monitors DiGiCo Rack, the Music Mix Mobile preamp rack, and the Denali Hydra; all on short W4 cables. This signal then goes to those mixing destinations through various forms of fiber. In this example, let’s say that RF #8 also gets a Pro Tools effect. The RF is patched into Hydra 1, Pair 8 and goes to Denali Summit, the broadcast truck, on a 500-foot TAC 12 fiber cable, where it is sent on a MADI stream over a 5-wire coax mult to Pablo Munguía’s Pro Tools mix position located in a nearby Gelco trailer.

After the RF has received the proper Pro Tools treatment, it goes back to split world on a three-hundred-foot W2 cable where it is patched into a music split. Let’s call it split A, Pair 52. That pair along with the rest of the music split inputs goes to the Music Mix Mobile preamp rack on a fifty-foot W4 cable and from there it is sent to the music mix trucks on fiber. RF #8, now a Pro Tools return track, is then mixed with the rest of the music inputs and sent back to the broadcast truck via an AES pair on a five-wire coax. The last stage is where A1 Mixer Tom Holmes combines RF #8 and the entire music mix with any other elements such as audience reaction and sends it to transmission on an embedded fiber. Quite a journey for our RF #8.

As you can imagine, there are hundreds of people involved in a show of this magnitude. It is advanced television. In our little B-stage world, there are audio, video, production, lighting, staging, props and backline people, plus the terrific techs and mixers that come with the artists, as well as some fantastic musicians. I am honored to work with all of them.

Interfacing with our mixers and techs is a true pleasure and I have great confidence just hearing their voices on my headset. Many people feel that they are among the finest at their craft. I can assure you, that is the truth. I would also like to extend my appreciation to the entire A-2 crew including the A-stage guys who really had a lot of big setups this year. The Dish Stage Crew that made bands magically appear on that very small space and the B-side boys who always make my Grammy experience so much fun.

I would like to add a special thank-you to head A2 Steve Anderson for reigning in the chaos that comes when you do a live TV show with twenty-five performances and for helping us stay on track to get through the long days with a sense of humor that Walter Miller might appreciate.

Yeah, probably not.

GLOSSARY

Denali Hydra: Denali is the broadcast facilities truck company used at the Grammys, Oscars and many other television events. Hydra is the stage box for the Calrec audio console found in the Denali truck.

DiGiCo Rack: A multichannel input/output rack connected to FOH and Monitor consoles.

Dish Stage Crew: Performances at the Grammys take place on three stages. The A- and B-stages are stage-right and stage-left sides of the main stage. The third performance area is the dish stage, which is a small performance area in the audience. Our crew is divided into the A-stage crew, the B-stage crew and the dish stage crew.

Fiber: A fiber optic cable for transmitting audio signals from one location to another. The Production Truck, the Music Mix Mobile Truck and the FOH and Monitor consoles are all fed by various systems through fiber.

MADI: Multichannel Audio Digital Interface, an AES standard protocol that carries multiple channels of digital audio.

W2: A sixteen-pair copper connection multi cable.

W4: A fifty-six pair copper connection multi cable.