by Mary Jo Devenney

1. INT. FILM SET — FIRST DAY OF SHOOTING

FRIENDLY CREW MEMBER

Hello! You must be our script supervisor.

ME

If I am, we’re all in big trouble.

Can you guess what I do?

FRIENDLY CREW MEMBER

Gee Mary, Set decorator? Props? Medic?

Teacher? Dialog coach?

ME

I’ll be your Sound Mixer.

Call me “Mary Jo” and no one gets hurt.

I don’t mind not looking like the person that people expect to see. I love being on a film set. It’s home. It’s comfortable. I know what needs to happen there. Years ago I was catching up with a friend from film school who was working in Post, and he laughed, “You’re a total set animal!” He was right.

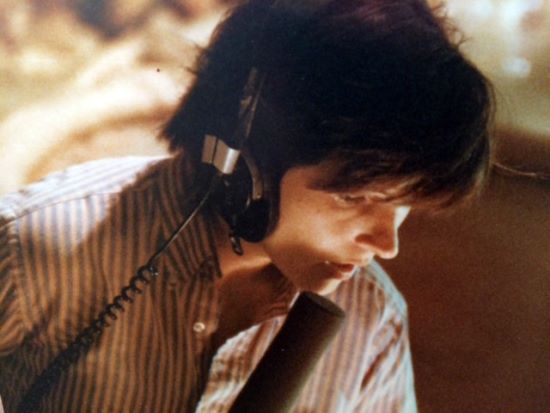

As a kid, I watched a lot of movies. I was an only child till age eight and went to an all-girls’ school whose vacation time was always longer than at my friends’ neighborhood schools. With much time to fill, movies became my friends too. After a women’s college in Massachusetts (What was I?—Nuts?), I drove from suburban Phillie to USC film school to experience co-education for the first time. Surrounded by film lovers, I totally fit in. We were making movies! The ultimate project for most of us was a class called 480. This course had five to seven student crews make sync-sound 15 to 20-minute mini-features. I shot one, recorded one and wrote and directed one. A couple months later, a classmate called to say he was “bailing” on a boom job and I should apply. They didn’t ask if I’d ever done it professionally, and I was off to Rochester, NY, to boom Fear No Evil, a horror movie that shot for nine weeks. I had the distinction of being the only crew member flown in from LA who was working for a totally deferred salary. I got $53/week per diem. As far as I was concerned, I’d arrived. This was before video assist and video village, so the Director, Script and I haunted the frame line during shots. Having just directed my own (student) film, I made lots of suggestions to the forgiving, first-time Director (What fun!). The last week of shooting, the Mixer had a tiff with the Producer and left. With a locally rented Nagra, a 415, a smart PA to boom and much apprehension, I mixed the last two days.

Back in LA, I couldn’t find a production job and wound up working at Richard Einfeld Productions, a little sound house. I did sound transfers, ¼” tape to 16 mag and 35 mag. I also auditioned and sold sound fx from a ¼” library that Einfeld had compiled with partner Frank E. Warner, the Supervising Sound Editor on some of the biggest films of last half of the twentieth century. I’d get calls to transfer some sound effect for Being There, and send it over to his editing room. On his next project, he came in and had me put tapes on the Ampex. “Get that loon (the bird) track out and load it backwards.” Then he’d manipulate the tape with his hands, slowing and ‘wowing’ it while I recorded it to 35 mag stock and voilà, it became the sound of a punch that would land on De Niro’s face in Raging Bull. As cool as this was, I found myself listening during transfers to what the crew guys said before “action” and after “cut” on the set of Roadie. I knew I should be on a set.

I was lucky to have a former co-worker remember me in a good light. The Key Grip on the New York film recommended me to Anna DeLanzo, an experienced Boom Operator who was about to mix a low-budget movie for Cameraman/ Writer/Director Gary Graver. She needed a Boom Operator and hired me. I have repeatedly discovered that you can never guess who might recommend you. It could be the usual suspects: UPMs, Directors, Post Production people, or it could be anyone from Grips or Accountants to DPs or ADs. On the film in question, one of the actors was Gene Clark, a veteran Boom Operator who worked with great Mixers like Jim Tanenbaum, CAS. So there I was: booming a Boom Operator for a Boom Operator. Both Gene Clark and Anna DeLanzo knew more about what I was doing than I did. I learned so much from them about the art of booming (and it is an art as well as a technical exercise) and this time I was actually getting paid a little! I loved/love booming.

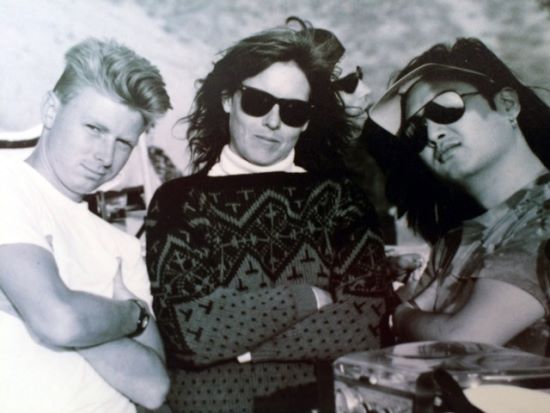

When I didn’t get calls to boom, I would mix. Ron Curfman was a Mixer of shows like Dallas and a shrewd businessman. He owned a little recording studio and told me and others that if we got mixing jobs, he’d make sure we had enough equipment to make it worth our while. Then he’d get the contract to do the sound transfers and the syncing of dailies to make it worth his while. If you needed work, you could make $10/hr performing these jobs on other people’s shows. A group of us met through him, boomed for each other and shared work. Decades later, several of us are still in touch and still sharing jobs.

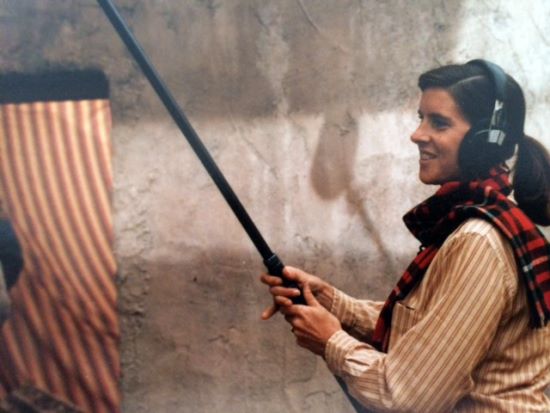

I got to work on The Executioner’s Song, an NBC miniseries that was nominated for the Sound Emmy. I also got to work on a movie in Spain called Hundra, the making of which was much more entertaining than the movie itself. I would plan the setup and then the Producer/AD would turn on the Nagra while I boomed.

OK, so in the midst of this I got pregnant. Would that affect work? I described booming to my doctor and he assured me that I was healthy and that prenatal kids are very well protected and I could stay as active as I wanted. So I did. Never considered petite, I ‘passed’ as non-pregnant for months, then entered a phase that still makes me laugh. People would look and I could see that they were about to ask if I was … but they’d stop themselves, realizing how embarrassing it would be if I answered, “No, not pregnant; I’m just a big girl.” As time went on, work got interesting. There was a lot of twisting sideways to keep my stomach out of frame. When moving between C-stands and the camera lens, what used to be accomplished with a gut suck now required deep knee bends to pass my neck through the tight spot. Maybe it was hormone-induced, but in the middle of a shot I’d think, I’ve got this guy totally on mic ‘and’ I’m making a human being. Talk about multitasking!

I was three weeks into the TV movie Murder: By Reason of Insanity and no longer ‘passing’ when, after the second sixteen-hour day in a row, I cried “uncle.” I was too tired. I’d had Laurie Seligman (great Boom Operator) standing by and asked her to take over. That was May 8. My daughter, Roma Eisensark, was born May 18. To this day, she knows when to be quiet on set.

That July, Russell Williams II asked me to work with him on Cannon Film’s Invaders From Mars. “You bet!” I said. Not only was it was always fun to work with him, but this precious, beautiful infant, while priceless, came with a big price tag. Invaders shot for twenty weeks. The lovely Louise Fletcher let me use her motor home as a bottling plant (don’t ask). A couple movies later, I got to work on the last five weeks of another non-union Cannon film, Masters of the Universe, with Ed Novick. Cards were signed. Cannon agreed to go union if there could be deals for projects under six million dollars, and with that, the union tier system was born. After seven years of knocking on 695’s door, I was in! (And I don’t believe Cannon ever made another movie in LA.)

I must interject a side note here as a few people who have seen this writing in progress feel that the sound person/ motherhood dynamic is important to my story. I was as lucky in parenting as I was in having the strength to work pregnant. My husband, Dave, is a writer and a wonderfully committed parent. He worked at home and carried the ball when I worked long days or nights. Of course, he did turn more to short stories during Roma’s first year and she could sleep with her head next to a Smith Corona electric typewriter. I think we all enjoyed my times of ‘unemployment’ when I could take over the caregiving. The three of us went to Philadelphia when I boomed Mannequin and Seattle when I mixed The Chocolate War. I had all the advantages of anyone with a work-at-home partner unlike many of my sisters and brothers in the business. Single parents are beyond heroic!

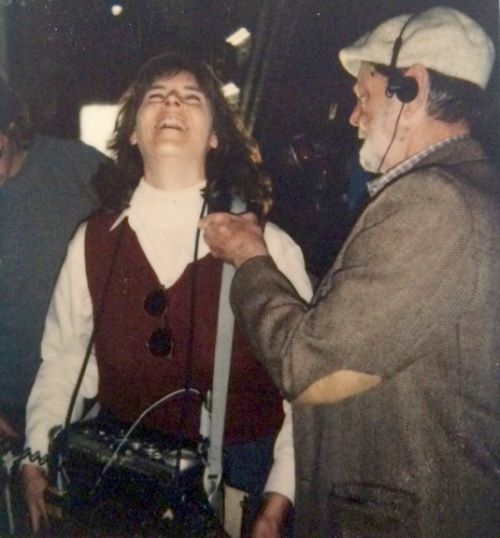

In the fall of 1989, Russell Williams was mixing the fourth month of Dances With Wolves. The show was going to go an extra month. (“Thank you” to the headstrong wolf playing Two Socks!) Russell had plans that would conflict, so he tapped me to come and finish the film. I still get goose bumps when I remember reading the script on the plane to South Dakota. It was great. I inherited the wonderful Boom Operator Albert Aquino, who, sadly, we lost three years ago. Everyone was friendly; there was just one problem. Most of what was left to shoot were tepee interiors. The plan was for the Special FX crew to do gas campfires via hissing pipes that the cast would sit around. I approached the DP, Dean Semler, not knowing then that this great Australian bear of a man was as much of a collaborative filmmaker as he was a visual artist. “Would it be possible to use real fire for these campfires?” I asked. “There’d still be noise but it would be the right noise.” “Well, that’s my main light source for these scenes,” he said, but “I’ll check with the FX guys to see what’s possible.” We went with real fire! Camera people have since told me that the visual warmth of real flames looks better than the bluish gas fire. Maybe it wasn’t a concession made for the sake of sound, but it’s been a great argument when I tell camera that one guy who went along with my request got an Oscar. So did Russell, and he mentioned me in his acceptance speech.

I could go on like this for another twenty-five years but, out of compassion for the reader and a realization of the size of this magazine, let me say that I have kept working to this day. Let me share some of my conclusions about being in our field.

A film is created in the editing room but, on set, we’re making the raw material. I’m always trying to hand over silk material from what is often a sow’s ear environment. It’s hard to re-create an actor’s magic if we don’t get it when it first happens, so capturing that moment is the goal. When we succeed, the magic and the budget both benefit. If the sound is good, I drive home happy even if the day’s been physically tough, or emotionally unpleasant. If I know the sound will need some fix in Post, I’m unhappy no matter how comfy the shooting day was.

As sound people we’re often at the mercy of others, so I try to speak everyone’s language. Working with every department (and understanding their goals and tools) will get you much further than many of the newest gadgets you can buy. (I am, however, grateful for radio microphones that work as originally promised decades ago. I’m also grateful for digital recorders with as many tracks as I have microphones so that Post can perfect my real-time mix. I’m particularly grateful that digital recorders won’t allow me to accidentally record over that last printed take that the Director asked me to cue up.) Being a woman might help in dealing with wardrobe and finding creative ways to hide microphones. Actresses are the people who most often say they’re glad I am a woman. I mention that I’m a recovering soccer mom and will leave this person looking neat. I suppose that’s proof that we’ll all play the stereotype card when it’s useful. But like all preconceptions, nothing’s true all the time. I try to evaluate mine often and dispel preconceptions about me. With a new crew, I always try to demonstrate that I understand what Camera, Grip and Electric are up against. It’s good to point out that the genny should move before the cab’s engine has stopped, and I always thank the people who have to lug out more heavy cable to reach it. There’s a line in the movie The Imitation Game that expresses my experience so perfectly. Joan Clarke explains why she’s been friendly to a co-worker that Alan Turing consistently antagonizes. “I’m a woman doing a man’s job,” she says, “I don’t have the luxury of being an ass.”

I talked to Brent Lang for a Variety (July 29, 2014) article about the small representation of women below-the-line in production. He asked if I was paid less for the same work. I said, in a sense, “yes” because I tend to get lower budget shows as a Production Mixer. Not only is there less money for sound but, as the budget falls, getting good sound tends to be harder. This is because of all the other money compromises, like worse deals on locations, older equipment used by other departments, smaller staff and shorter schedules. Of course, the boys work these shows too, but it sure feels like they move on sooner. (Again, nothing’s true all the time.) The positive side of low budget is the chance to master knowledge of new wave equipment and practices that will make their way up the production ladder—wide-and-tight, RED camera, ‘D’ cameras, etc.—before the rich producers start to use them. It’s also a chance to be available for the occasional innovative or true “labor of love” film where you can feel very appreciated and integral to its success. I’ve been lucky to see some really good movies while I was recording them. (Including two movies that my husband wrote and produced, one of which was Monkey Love, a comedy starring Jeremy Renner in 2004. Yes, shameless plug.)

My parents chose a girl’s school partly to round out their little tomboy. It probably had the opposite effect. If you wanted to do something, there was no one to stop or slow you down by “helping” you. It wasn’t the place to learn about gender norms. There was no reason not to be a leader. You could be the president of the dramatic club or on the school paper or on the varsity basketball team. If there was a drawback, it was that I didn’t learn to navigate a system that treats you as different or less acceptable. I still work at understanding why people would object to you doing whatever you’re able to do. When we get out of the pass-van on a location scout, it feels a lot like taking the field as a member of a team on which I’ve earned my spot. I loved that feeling in school and love it now.

The bottom line is, it’s a great job. If it’s taken a bit more time and work because of artificial obstacles, I figure you just take a little extra pride in what you do achieve. I owe a tremendous debt to the 695 “brothers” that I’ve worked for, and with. I was going to list them but it’s a very long list. I cheer their successes and those of my ever-increasing number of sisters.

PS: As I write, it is over a year since the loss of my friend and mentor of longest standing, Lee Strosnider. He was perfectly generous and professional. He would explain equipment and rent it to me at all hours knowing I’d pay when possible. His stories and nuggets of advice were as interesting as they were long. I miss him.