Living with Hearing Loss Attenuation, Isolation & Adaptation

by Bruce Beacom

At the age of twenty-five, I started my career, humbly in 1995 as a studio PA, at a recording studio in New York City called National Sound at the National Video Center. I worked my way up to become an Assistant Engineer; handling all the daily loads of projects to be mixed, creating music bed playlists to be licensed and used in editing sessions, extensive mic setups in sound booths for music, and voice-over recording sessions and handling duplication requests of all formats for nationally broadcast and syndicated TV shows. It was a great way to cut my teeth in the TV industry, but after three years of not seeing the sunshine, I knew I needed to be out in the field. I left post and started ENG mixing doing corporate freelance work during the day and for four nights a week, I worked at a live music venue called ‘The Living Room’ in the Lower East Village, mixing three to five bands a night. It was exhausting, but I was immersed in mixing on two separate fronts and loved it. In 2000, I moved back to Los Angeles, where I had gone to college, transitioning solely to mixing for unscripted and reality TV. Notable productions I’ve worked on are CBS’s The Amazing Race (fifteen consecutive seasons) for which I received three honorary Emmy certificates for my contributions as a Sound Mixer. HBO’s Project Greenlight (Season 4) for which I was nominated for an Emmy for Sound Mixing, Bravo’s Top Chef, ABC’s American Idol, The Bachelor and Netflix’s recent notable documentary, Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich.

As a singer, songwriter, guitarist, I have produced two records, and I am currently writing material for my third. My band and I have performed regularly in LA at iconic venues such as the Troubadour, The Roxy Theatre, The House of Blues, The Viper Room and many more. If it weren’t for my love of music, I realize I would not be a Sound Mixer today, as the two are inextricably connected and both rooted in the other.

If anyone were to tell me at thirty that I would be spending the next eight years of my life losing ninety-five percent of my hearing to an invisible hereditary disorder, and fighting to get it back, I would’ve never accepted the challenge. I had no choice though. With everything I’ve been through, I clearly understand that when a challenging event occurs in our lives, it’s not the event that defines us, but how we choose to handle it. I chose to never give up hope, and I painfully learned what it means to become an advocate for myself, and to never stop searching for answers.

Losing my hearing educated me to appreciate what I had lost, and to take nothing for granted. It taught me about survival through adaptation, by which I found ways to keep writing music and mixing sound. In the first three-plus years of my hearing loss, I adapted to mixing by monitoring my headphones in a “mono” setting, and turning the volume up to a point that I could feel the vibrations. I developed a keen sensibility for paying close attention to the VU meters like never before. As for my music, I adapted by playing my acoustic guitar as an electric. I can feel the acoustic vibrate against my body, which puts me more in tune with the instrument. I still continue to play this way even after getting my hearing back, as it led me to develop a sixth sense with my acoustic guitar. It’s a style and sound which I would have otherwise not discovered

Bruce at The Viper Room, 2019. Photo by Darren Bunkley

Booming rapper/recording artist Ludacris on YouTube show

’Best Cover Ever’ in 2017

ENG bag mixing/booming on American Idol 3. Oct. 2019. Photo by Kako Oyarzun

The ringing in my ears started in my late twenties and to say it caught me off guard would be an understatement. I had normal, healthy hearing until I was about twenty-nine years old, but that’s when I first began to notice signs that something was very wrong. It started slowly in the beginning with sporadic ringing, sometimes accompanied by buzzing, clicking sounds, and even pulsating sensations, like crickets chirping that would sometimes have the ability to throw me off balance. I didn’t think much of it at first as it was very irregular, happening only one to three times a week just for a few moments each time. As I reached my early thirties, these episodes became frequenter, more pronounced and almost constant to the point where they began interfering with my daily life and communications with others.

As a musician and Sound Mixer, protecting my hearing has always been one of my highest priorities. I was confused as to what was happening to me, but I was very proactive in searching for answers to uncover the underlying cause. The path to my diagnoses was uncertain, fraught with dead ends, with many unanswered questions, and at times it was simply terrifying. I spent the next few years going to numerous doctors, ENT’s and specialists, undergoing many forms of diagnostic testing, but not one doctor could give me a clear answer as to why my hearing was in such decline. The vast majority said I had severe tinnitus, with many misdiagnoses; one doctor even telling me I had lupus, which was later retracted. The entire experience was exhausting and unnerving.

At the age of thirty-two feeling helpless, I begrudgingly got fit for a cheap pair of hearing aids; not an easy choice or reality to accept for any musician or Sound Mixer. To say the least, it was humbling. The hearing aids were helpful at first, amplifying external sounds above the volume of the ringing inside my head, and allowing me to adapt. It was short-lived as my hearing continued its rapid decline, so much so that within a year, these cheap hearing aids had no benefit in overcoming the ringing at all. Even if they were turned all the way up, they would just feedback in my ears and create more confusion in my head. After years of searching and still no definitive answers, I was in a dark place, isolated and ready to give up.

I felt the only option left was to seek out a better and more powerful pair of hearing aids. With my wife Holly by my side, we found an Audiologist in Culver City, by the name of Dr. Sol Marghzar. During my initial screening, he discovered that I now suffered ninety-five percent hearing loss in both ears. To our surprise, he said he wasn’t willing to sell me new hearing aids until I had specialized surgery on both of my ears. Holly and I were both stunned, but it was the exact bit of elusive information we’d been searching for. There were so many new questions: “Surgery?! What kind of surgery? What’s it called? How? Where? When?” After all this time of being lost, perhaps there was a reasonable explanation to my dire situation. Honestly, this was the first moment I recall feeling some semblance of hope.

Dr. Marghzar suspected I had a rare genetic hearing disorder called ‘otosclerosis’ which is inherited, and caused by an abnormal overgrowth (mineralization) of bone in the middle ear. This condition stops one of the three bones (the stapes) from vibrating, therefore limiting the transmission of external sound from the outer ear (tympanic membrane/ear drum) through the middle ear (hammer, anvil, stapes) to the inner ear, (cochlea) where the signals are then sent along the auditory nerve to the brain.

The World According to Jeff Goldblum, on March 2, 2020. Photo by Ross Alexander Wilson

If his conclusions were correct then I could be a candidate for surgery called a ‘Stapedectomy.’ This is a specialized procedure where the diseased “stapes” bone in the middle ear is removed, and replaced with a titanium prosthetic. Once healed the new bone allows sound to pass normally through the middle ear to the inner ear.

Dr. Marghzar recommended I go to the House Ear Clinic in Los Angeles. He then put me in touch with Dr. William H. Slattery and got me an expedited appointment with more blood tests and another CT scan to confirm his suspicions. In the meantime, Dr. Marghzar loaned me a pair of higher quality hearing aids, which helped me to continue working and adapt to daily life.

After further testing at the House Ear Clinic, the results confirmed Dr. Marghzar’s findings; my prayers had been answered. I was scheduled for my first of four ear surgeries with Dr. Slattery, between 2004 and 2007, which restored as much of my hearing as possible. Most cases of otosclerosis requires only one surgery for each ear, mine was so bad that I needed two for each ear (initial surgery and a revision). You can only have one surgery done at a time which required a six-month recovery between surgeries. As they were staggered over four years, it felt like a long endless road.

To better illustrate what was happening to me, it helps to draw a comparison between the anatomical functions of the ear and the mechanical functions of a live PA system. Think of the ear drum (outer ear) how the diaphragm in a microphone works by picking up acoustic energy—sound waves and transmitting them through a connected XLR cable, (middle ear) into the PAs amplifier, (inner ear) where they are then amplified and made distinguishable (the brain). Now, imagine if you were to impede the signal flow through the XLR cable, or even worse, cut it off altogether with wire cutters? The outcome is obvious. No sound waves can now pass between the microphone and the amplifier. This is exactly what happens to a person living with Otosclerosis. It’s also called “conductive hearing loss,” because the bones in the middle ear (XLR cable) stop working as a conduit to the inner ear (amplifier).

As for the internal ringing which accompanies otosclerosis, it’s my understanding that much of mine was generated by the abnormal growth of the stapes bone. In a normal situation, the bones in the middle ear only move when the ear drum vibrates in reaction to external sound waves. As the diseased stapes bone mineralizes, it slowly freezes into place against the cochlea, therefore generating the excruciating internal ringing, screeching, clicking, and buzzing sounds that otherwise do not exist externally. It can be absolutely maddening.

First show back since lockdown. Quibi socially distant Zoom interview, June 22, 2020

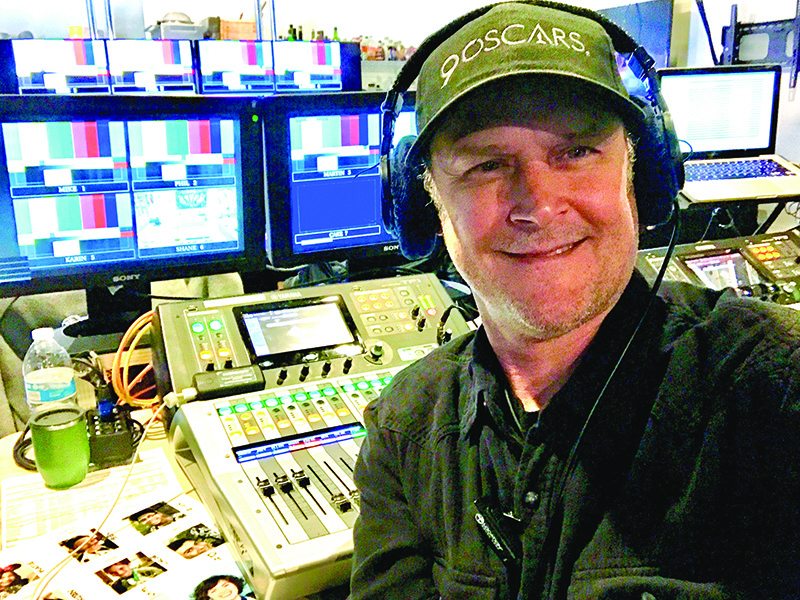

Mixing on a Soundcraft Vi4 console for a live satellite

feed for Farmers Insurance, January 2017.

Today, I have titanium prosthetic bones in both my ears, and I have regained sixty percent of my hearing. Additionally, Dr. Marghzar fitted me with digital hearing aids gaining twenty percent more and bringing my hearing to about eighty percent. I remain vigilant in managing my hearing loss and preserving it. Otosclerosis is a progressive disease, which if left unchecked, and without taking a daily prescribed dose of a fluoride-calcium called ‘Florical,’ it will revert to where it was before my surgeries, and do further damage to my inner ears (cochlea), which is non-correctable.

After everything I’d been going through, the one hurdle I never expected to face—and one that completely blindsided me—was discrimination at work. I know it sounds unimaginable but the bias is very real and exists within the TV industry. This challenge I found to be just as hard to cope with as overcoming my hearing loss. Specifically, because you can’t control someone else’s lack of compassion, education, or willingness to understand a person’s handicap. There were many occasions where I found out, after not getting a job, that I wasn’t hired because an Executive Producer or Supervisor didn’t want to hire a Sound Mixer who wears hearing aids. I became so dismayed with this reoccurrence that it led me to ask many new questions and also take note of certain biases within our industry; how many Camera Operators wear eye glasses (a lot)? I ask this; “If it’s perfectly OK for a production company to hire a Camera Operator who has ‘assisted sight,’ then why is it not ok to hire a Sound Mixer who has ‘assisted hearing’?” This was an epiphany for me and it became my rallying battle cry from that moment forward in order to open people’s minds to this prejudice within our industry. I’ll never forget the first time I employed this analogy when speaking to a Line Producer who was clearly on the fence about hiring me by asking, “aren’t you the deaf sound guy? The one who wears hearing aids?” I responded, “Yes, I do wear hearing aids, but how many Camera Ops have you hired who wear glasses? What’s the difference?” First, I was met with silence on the other end of the phone, and then a reply I didn’t expect, but was happy to hear “Well, you make a very good point there.” It was literally music to my ears because for the first time, I felt like I had gotten through to somebody. I also realized that I was still having to learn to be an advocate for myself, but only now in this completely different context.

There’s not one day that I’m not thankful to Dr. Marghzar and Dr. Slattery for saving my hearing. First thing I do every morning when I wake up is put my hearing aids in, turn them on and I am beyond grateful when the sounds of the outside world begin to filter through and I can simply hear my wife and son’s voices. To be able to continue writing music and working professionally as a Sound Mixer is even more than I could have ever hoped for. Without the love and unending support of my wife Holly, I’m keenly aware that I would never have been able to get through any of this. I have so much gratitude for it all with the lessons I’ve learned. It is my hope that by sharing my story, I can help to inspire others to keep searching, especially in the face of overwhelming circumstances, and in turn, become advocates for themselves to never give up.