The Traveling Road Show on Mad Max: Fury Road

by Ben Osmo

Our mission was to record dialog and sound effects while constantly in motion. We set up three multiplex systems to give me a range of one to three kilometers (about two miles). This became a necessity after the first run through with the Armada, where they took off to a distance of seven kms (four miles). I relocated all my equipment into a small 4WD van and followed the action. The crew dubbed it The Osmotron.

The Osmotron

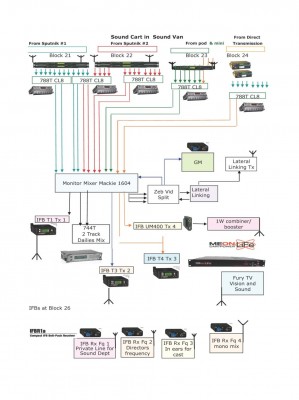

My setup included four Sound Devices 788T, each with a CL-8. I did a mix down to each recorder as well as a two-track mix to a 744T for dailies. There were six Lectrosonics Venue receivers on Blocks 21, 22, 23 and 25, as well as two VR Venue Field receivers on Block 24. One Mackie 1604 for monitor mixes, four LectrosonicsIFB transmitters and three video monitors all powered by a Meon, a Meon Life and one more UPS (see Schematic #1).

When traveling, the equipment was powered by a 2k generator mounted on the back of the vehicle.

I was happy that all of the 788Ts had SSDs (Solid State Drives), as most of the filming was off road and they performed exceptionally well under extreme vibration. They were in road cases that were well insulated. The 744T was suspended in a pouch, so it could absorb the many bumps in the Namib Desert for six months.

The eight principal cast riding on the War Rig wore Lectrosonics SMV or SMQV transmitters on Block 24 with DPA 4061 lav mics. I find the DPA microphones quite transparent and the best for wind protection.

Andrea Hood, the genius Set Costumer, helped us enormously by designing a system to attach the packs and pre-sewing the lavs on costumes. I am forever indebted to her help. We supplied the lavs and packs at the end of each shooting day, as Andrea had to have the outfits washed.

There was an antenna hidden inside the cabin of the War Rig, with a coax cable to the interior of the tanker to two Lectrosnics Venues, Block 24 with their outputs to twelve Lectrosonics UM400 transmitters on Block 21. RF Engineer Glen English in Canberra, Australia, multiplexed the RF out of Block 21 to a specially designed RF combiner/ booster.

All this was in an “E Rack” ruggedized road case with a Meon UPS. In the back of the case was a cooling system, as it got to above fifty degrees Celsius (122 F) and very dusty inside the tanker. We called the road case the Sputnik (see Schematic #2). There was a 10k generator in each War Rig for special FX, lighting and sound, so I was able to tap in to this to run the Sputnik.

From the RF combiner/booster, one coax went up the inside of the War Rig, where we hid a transmitter aerial on the top, above all the metal, giving a 360-degree line of sight.

We built Sputnik #1, Sputnik #2, as well as Pod #1 with one Lectrosonics Venue and six UM400s. A small generator or the power from the Edge Arm camera car could run Pod #1.

Additionally, we had a Mini Pod, with three channels, that was battery-driven for use on small vehicles. Three Lectrosonics 411 receivers Block 25 and three UM400 transmitters on Block 23.

The Sputniks and Pods were shifted to different vehicles, as required. The main cast were on Block 24 and kept their wireless packs as they moved between one of four War Rigs that were in different stages of art department breakdown, for different camera and driving configurations, or special FX requirements.

At the same time as recording dialog, we also tried to grab as many sync sound effects as possible. We placed a lot of hidden microphones in the cab, in the engine bay, near exhausts, transmissions, on the top of the War Rig, in other vehicles and on the vast supporting cast.

I was in The Osmotron, with Erwin our van driver, a local safari guide. We never got stuck anywhere!

There were times, in close proximity, that I was able to record direct with the Venue Fields on Block 24 and bypass the repeaters. But all the exterior vehicle microphones were direct, either on Block 24 or Block 25.

Traveling long distances meant the walkie-talkie repeater towers were often out of range. I provided my Lectrosonics wireless and IFB comms to Director George Miller and First AD-Producer PJ Voeten. They too were great distances apart and now able to have hands-free communication. Additionally, Cinematographer John Seale, two of his Camera Operators and the First ACs were on this system.

George might be in his van with a few monitors, traveling behind the action and discuss shots with PJ and John and the Edge Arm crew that were shooting other angles. Or, George would be in the Edge Arm vehicle, while PJ and crew were on the War Rig or other tracking vehicles.

This also helped some of the cast. Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne) would be in the extremely loud Gigahorse vehicle, where you could barely hear yourself think. We put a DPA 4061 microphone inside his mask and an IEM (In-ear monitor) to a Lectrosonics IFB receiver, so conversations were able to take place.

Iota was Coma on the Doof Wagon; he played the double neck guitar with flames. Iota wrote some guide temp music with drums and guitar whilst in Namibia, on Pro Tools. I imported the sessions and transmitted him a mix via an earwig.

Iota had no dialog, but wore a mic so he could communicate with George Miller, PJ Voeten, my crew and me. The vibrations were so intense when traveling off road, my laptop kept crashing. I quickly downloaded the cues to my iPod, it worked well and later, to an iPad. There were also four drummers that had to keep time, they also had IEMs.

Mark J. Wasiutak was the Key Boom Operator; he was also on the first Mad Max. Mark traveled wherever the cameras were set up. Mark was able to troubleshoot the War Rig, slate the cameras as backup and record sound effects. And of course, as the Key Boom Operator, Mark was in charge of booming whenever we had traditional setups.

For timecode, Ambient master clocks were used with GPS antennas set to Greenwich Mean Time. All the cameras and Denecke timecode slates were supplied with Ambient Lockit boxes. My 788T recorders and the 744T were jammed from the same Ambient master clock.

The two-track mix down was transmitted to our genius Video Assist, Zeb Simpson, who was in a larger truck with an RF trailer that had a forty-five-foot telescopic tower with microwave and UHF antennas.

Sam Sergi, our sound department RF Engineer, modified one of my IFB receivers with an SMA connector to facilitate a connection to a large Wizy antenna that was also on the forty-fivefoot mast. This gave us a range of at least five km (three miles) to send a mono guide to video assist, so Zeb could compile the action and drama sequences from both main and action units for Director George Miller. Using our IFB comms, Zeb could talk to George remotely. Thanks to support from Greg Roberts, of Lateral Linking Broadcast Pty Ltd, Zeb was able to show George cuts, loop playback and show various live cameras, including the Action Unit.

On the last weeks in Namibia, we set up my assistant, Oliver Machin, to record specific vehicles with a 788T, hard-wired and multitracked. Oliver was fastidious with his recording and logging of his sound reports. He did a great job.

Derek Mansvelt was the Action Unit Sound Mixer from Cape Town who, with Boom Operator Ian Arrow, duplicated a smaller version of my rig in a van and chased the stunt teams and vehicles around the Namib Desert for a few months, recording vehicles, explosions and crashes.

Finally, we were off to Cape Town Studios, where green screen components were filmed. It was still a hostile environment; in order to simulate the wind and dust, large Ritter fans were used.

I continued to mix in the The Osmotron as there was no time to reconfigure. We parked it outside the soundstages, cabled inside to Video Assist and our antennas. Along with the usual comms and talkback for George, PJ and the camera crew, we also needed a VOG with handheld Shure SM 58 microphones with on-off switches into Lectrosonics plug-on transmitters. I continued to use the in-ears for Immortan and Coma, and smaller battery-powered speakers, placed in vehicles for communication and playback.

After a break for a few months of editing, we regrouped in Australia, for the crucial Citadel sequences. The exterior Citadel location proved a challenge again, as it was spread out, 100m wide by 200m long (328 x 656 feet). We rented two large speaker stacks for the VOG, from Slave Audio in Sydney and our gentlemen grip department built us scaffold towers on either side of the large set.

The Citadel sequences proved fun for the Boom Operators, as they were in costume and makeup so they could wander amongst the crowds with the costumed Steadicam crews. It was a great opportunity to record large crowds with multiple booms.

The interior of the Citadel was back in the studio, with very large sets as well as tunnels. The VOG was still in use as well as in ears, for drummers.

I reconfigured my equipment to two sound carts and no longer required the Sputniks and Pods.

The two carts contained two 788T with CL-8, a 744T, Pro Tools 10, a Sonosax 10SX, Mackie 1604 and Yorkville PA. Three Lectrosonics Venues, four Lectrosonics 211 receivers, four Lectrosonics UM 200 transmitters (for additional comms), eighteen Lectrosonics SMV and SMQV, DPA 4061 and 4063 lavaliers. Four Lectrosonics IFB transmitters, along with twenty-four receivers. Boom microphones were Schoeps CMIT 5U, Schoeps CMC5 with MK41, Sennheiser 416 and 816. A Nagra 4.2 for loud vehicle crashes a Meon UPS and Blackmagic HD monitors.

I must acknowledge Sound Designer Wayne Pashley and his team at Big Bang Sound, who initially took on the job and constructed the fundamentals.

Later, Sound Designer David White came on board with his team at Kennedy Miller Mitchell and continued to work closely with George Miller to come up with the brilliant tracks.

In fact, hats off to all the Post Production teams and Re-recording Mixers in Australia and the United States, who did a bang-up job on the final mix.

It was a real adventure and I feel privileged to have been a part of this iconic film and very proud of the amazing international cast and crew that contributed to this film above and beyond.