by Lee Orloff CAS

One of the benefits of having been in the industry for quite some time is that I can now find myself discussing work on a project I first caught wind of nearly twenty-five years ago, Michael Mann’s Ferrari. The filmmaker and I had initially worked together in 1994 on Heat. There’s a reasonable chance a few of you might not yet have been born. I first learned Michael Mann was developing his film to tell the story of Enzo Ferrari roughly between 1999’s Ali and 2003’s Collateral.

The film is set during the summer of 1957, a volatile time for Ferrari when his business is being threatened by bankruptcy. His marriage, battered by the recent loss of his son, Dino, and his long history of philandering, has culminated in Enzo struggling to acknowledge his son, Piero, with Lina Lardi. The domestic drama runs headfirst into the preparations for, and running of the grueling cross-country race, the Mille Miglia. I was familiar with the period, having read Brock Yates’ biography, Enzo Ferrari: The Man, the Cars, the Races, during the years when the film was in development.

Michael Mann has long been associated with Ferrari, dating back to his 1980’s series Miami Vice. One of the most memorable scenes for many fans of the show occurred in an episode in Season 3 when Crockett’s Daytona Spyder is blown up by the Stinger-wielding arms dealer, leading to the Testarossa’s introduction in the series. Michael drives a Ferrari. I remember seeing the latest model he’d received while we were shooting either Collateral or the HBO series Luck. I am aware of a relationship he developed with Piero Ferrari, the Vice Chairman, without whose trust this film could have never been made.

Ferrari is a testament to Mann’s decades-long efforts to bring his passion project to the screen. He brought his deep appreciation and understanding of racecraft to portray the drivers and the part his race cars played in the open road Mille Miglia with an unwavering commitment to authenticity and through the sharp focus of his legendary attention to detail. But it is the struggle and triumphs witnessed in the characters’ lives that resonate at the heart of the film and drive it to its conclusion.

I and longtime Boom Operator Jeffrey Humphreys were brought to Italy to shoot the drama portion of the film …certainly an atypical arrangement for me. However, by July, rather late in pre-production when we were hired, I had already been committed to another Atlanta-based project which was scheduled to begin principal photography in October. An Italian crew was hired for the race portion, and fortunately for us, we were able to hire Luigi Pini, who would continue on the show as Boom Operator once the Italian mixer, Angelo Bonanni, took over to start the production with us, providing valuable continuity during the entirety of the shoot.

Having many of the same U.S. crew members onboard who had previously collaborated on Michael Mann’s films helped to expedite the process of bringing multiple departments together to develop solutions for production challenges as needed. Being an Italian citizen and having periodically spent considerable time there over the past few decades, I was quite familiar with the practical and cultural differences we would encounter during the summer shoot in our principal base in Modena, as well as in the surrounding areas of Emilia-Romagna. Although since I was last there, all of Italy seemingly has embraced WhatsApp as its primary choice for nearly all forms of communication.

I can count on no more than a few fingers the number of elevators we happened upon during the shoot. I owe my deepest respect to Jeff and Luigi for all their teamwork. I also emailed Ron Meyer @ PSC for the spot-on research that went into nailing down the specs of his trusty PSC Eurocart. Although it had been designed during a much simpler time when production sound didn’t carry nearly the quantity of items we currently do, it adapted well and turned out to be one of the very few wheeled carts anyone was able to squeeze into one of the two-person lifts. Moreover, it provided me with a handy platform for keeping the bag rig off my shoulders during our shoot. It allowed me to set up in more storage closets, pantries, and balconies than I ever would’ve sandwiched into otherwise—complete with monitors and a mini forest of Teradeks which allowed us to keep up and kept network cabling and umbilicals right where they ought to be—in sealed cases on the truck. Elevators probably took a close second to the rarity of finding air conditioning, though that didn’t stop production from finding ways to bring A/C into every set, with industrial-sized units crowding the narrow streets and alleys, thereby making both ingress/egress and navigating through the tight interiors even more challenging. In their defense, production didn’t have much choice. Europe was suffering through a blisteringly hot July and August, but all of the power and flex hoses really added to the challenges of buttoning up interiors from the intrusive exterior sounds of modern-day Modena and Reggio Emilia. Many thanks for the help from the unit, production, and electric crew.

As an example of challenges and solutions in getting set up for the day’s work: one of the scenes we were shooting was in the garret of a stately five-story villa with a fragile old stone staircase with wrought iron railings overseen by a persnickety property manager, or possibly owner. Thankfully, gear could be hauled up in the basket of an exterior lift and then pulled in delicately through a barely large enough opening. A portion of that day’s work concerned a flashback scene with Enzo, Laura, and a very young Dino that was a component of a central montage in the film involving a performance of an aria from Verdi’s La Traviata. In addition, there was all the usual gear required for music playback. Typically, I would be handling playback, except for the two days in which we were recording live performances, one of them being when we had Angelo with us for the shoot of the aria at the Teatro Comunale Luciano Pavarotti-Freni di Modena Opera House, and the other when we brought Alessio Ombres on for the choir at the Workers’ Mass scene, which intercuts with the Orsi brothers’ time-trialing their Maserati 250 at the Autodromo.

1953 Ferrari 250 Mille Miglia PF V12

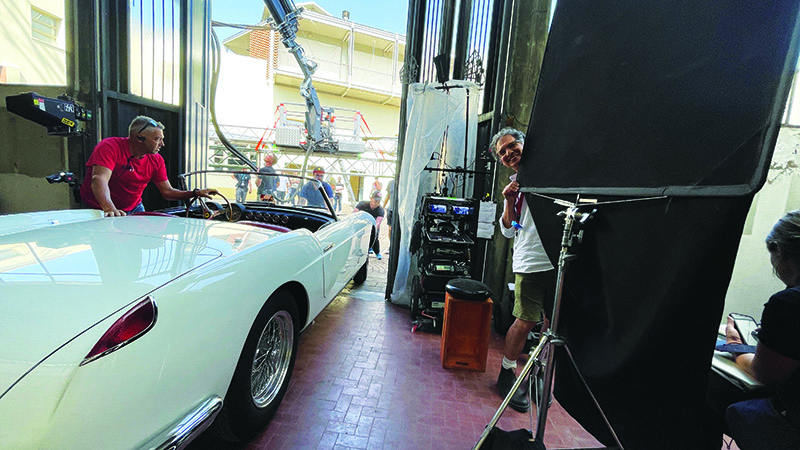

How the iconic period cars at the very heart of the story were brought to life on the screen visually and aurally requires more than a simple relating of the approach used to protect production dialog in order to ensure integrity of the performances. Race cars of that era and publicly available street versions configured with similar drivetrains are either largely gone forever or are now considered to be precious museum pieces of handmade industrial art. Now worth many millions of dollars, they are cherished trophies in privately held international collections. In fact, we were shocked at the number of original, drop-dead gorgeous cars which showed up on set to add an unmistakable mark of authenticity. All of which were given the appropriate star treatment, with motorsport teams rolling them into position with gloved hands while the shooting crew were instructed to respect the strict no-encroachment perimeter protocols that were put into place. Many of the background cars were driven by their proud owners. We were regularly treated to awe-inspiring parades of rare period examples. Most of the hero cars with few exceptions were builds from the ground up done in the UK, with custom fabricated coachwork, constructed around chassis housing modern turbo four-cylinder engines designed and engineered for the unique demands of the production. The discussion on how to best limit the undesirable impact of these inauthentic race engines on the production tracks had been brought up from the outset. I was cognizant that Michael Mann’s approach to the action would necessitate engines to be running in and out of dialog in many of the scenes such as ones at the Autodromo test track and in the pits, both at Brescia and Bologna. As a solution, we agreed that by having the actors keep their levels up as would naturally occur in these situations along with the use of lavaliers, we should be successful in improving the balance between dialog and the turbo four’s sound. According to Supervising Sound Editor Bernard Weiser and Re-recording Mixer Andy Nelson, that approach proved to be enough to allow post to dial it out sufficiently and to be covered by the accurate and beautifully recorded sounds of the Ferrari V-12s and Maserati V-8s captured by the UK’s Sound Effects Recordist Chris Jojo. As can be well imagined, it turned out to be no small feat finding owners of the appropriate vehicles who were willing to bring them to the country racetrack and run them at race speeds in order to capture everything that was needed. Re-recording Mixer/Supervising Sound Editor Tony Lamberti explained that the path leading to finding the right owners involved considerable research. In the end, they needed to lean into the support of Pink Floyd founding member and drummer, Nick Mason, his family members, and others asking for favors of members of that elite club of Ferrari owners to cement the deals.

In some ways, Michael Mann’s approach to the sounds of the race cars in Ferrari reminds me of his approach to the prominently featured gunfire on Heat in the shootout on 5th Street in downtown LA. This was not destined to be business as usual. Stunt Coordinator Robert Nagle, another longtime Mann collaborator, and “Biscuit” Rig Operator, was brought in during post as a race advisor at an effects spotting session as the team was developing that aspect of the sound design. Rather than have the post team pitch shifting and/or time stretching the recordings to shape engine and exhaust sounds, Michael’s command was for them to be captured naturally to replicate authentic race-craft, so that any racer experiencing those scenes in Ferrari would feel them as real. Tony and Chris had multiple Zooms in which they thoroughly dissected the highly detailed race and time-trial blueprint for each of the up/down shifts, revs, and the frequency interplay between engine combustion and exhaust volume in determining the best microphone configurations and perspectives to utilize for the sound effects recording session.

The “Biscuit” or more accurately the “Biscuit, Jr.” is the second generation of Allan Padelford’s innovative camera car originally developed in the early 2000’s for Seabiscuit. Among its numerous design features is a driver’s pod which can be shifted around the platform to accommodate various camera positions. On Luck for scenes at the Santa Anita racetrack where it was rigged with a mechanical horse, the “Biscuit” allowed Michael to shoot actors immediately alongside the field of ponies. Due to the length of the racetrack oval, we embedded audio into the microwave video transmitter for sends. On Ferrari, that option was available, if necessary, to provide audio to Michael Mann in the Sprinter command van if he chose to be stationed there for the extended Mille Miglia sequences. As things worked out, much of the race work was a combination of mounts and/or the Pursuit vehicle. Recorders tucked away and lashed down in the race cars provided confidence and redundancy while the mix utilized RF links to chase vehicles.

“We’re going to record the opera live.” With those seven words delivered from Michael in pre-production, the marching orders were set. There was a slight wrinkle, in that there wasn’t a music supervisor on the show, but anything’s doable if there’s enough time to discuss it all, reach a consensus, and then have multi-department coordination. All of which we had, if not necessarily within an ideal timeframe. The aria is “Parigi, o cara,” La Traviata, Act III. The reference Michael had for the aria was the 1981 Decca recording performed by Dame Joan Sutherland and Luciano Pavarotti with the National Philharmonic, conducted by Richard Bonynge, Sutherland’s husband. The film’s performance of the aria, a duet between soprano and tenor, would take place at Modena’s iconic Pavarotti-Freni Opera House. The aria was only one of many scenes to be shot that day which Michael’s first AD, Joe Reidy, had us scheduled for. It included cast entrances, orchestra tuning up, various points of view from the upper boxes, and a scene involving gamesmanship between Enzo and one of the Orsi brothers of Maserati.

It turns out the venue was booked for another performance the evening before the art department’s prep day. The orchestra members had arrived the afternoon before the prep day for fittings. The same was true for the soprano, although the tenor had been in town previously as he had been needed for other scenes. Pre-records of the vocals and the orchestra would be required, since if we were going to shoot the hero coverage of the duet live, we knew based on established operatic convention that we’d be limited to no more than two takes from the vocalists. All the wide shots and overs and all the coverage of the audience would be done to playback. Based upon my familiarity with Michael’s shooting style, I was fully aware we would never be given sufficient time to do a simultaneous live recording of both orchestra and duet. Since it was clear after doing extensive research that there were no appropriate recordings available of the famous aria with separate orchestral stems, a decision was made to do a pre-record with the cast orchestra and vocalists. The prep day for art, electric, and others (us) was a main unit shoot day. There weren’t any nearby studios large enough for an orchestral recording and Rome was just too far away. The art department was too pressed for time to take any of it out from their build day for us to be in the opera house doing pre-records. However, there was a nearby town, Carpi, which I had cycled through on a day off that had a beautiful, if slightly less grand, recently renovated opera house that would fit the bill. Fortunately, Angelo was available to travel up from Rome to handle pre-records. We had already shot scenes containing the aria and decisions had been made regarding the entire sequence, including at which point the flashback scene would occur. Our Editor, Pietro Scalia, participated in the session to supervise, providing the click and timing. Angelo and his assistant removed the first four or six rows of floor seating for the orchestral placement, so the recording would better replicate where they’d be heard in the scene from the deep pit of the Pavarotti opera house. The three omni heads on a Decca tree plus a pair of outriggers were supplemented with an Ambisonics mic, figuring those additional tracks from the classic horseshoe-shaped opera house might prove useful. After a couple dozen or so headsets were distributed as needed, everything was set. Ultimately, the conductor said he couldn’t conduct to a click track, so after a couple of rehearsals, they were dropped, but Pietro was satisfied with the timing of the freely run recordings. The final scene came together well.

Having Michael include Jeff and me on this deeply personal project was highly satisfying. Being back in Italy for the shoot reminded me of how much I had been missing it.