© 2023 Paramount Pictures

I was no stranger to the Mission: Impossible series and have worked on several films with Tom Cruise. Dead Reckoning Part One was my third outing in the Mission: Impossible franchise, following Fallout and Rogue Nation, all directed by Christopher McQuarrie and of course, starring Tom Cruise (TC). I also worked with Chris McQuarrie (McQ) when he was the writer on another TC project that I worked on called Valkyrie.

One of the advantages to having the writer as director is that on the previous two films, the script was continually evolving during production and even in post production. It is not unusual to complete principal photography and then return for several weeks of additional shooting to hone the plot and storytelling arc. This, my third film in the series, not counting some work that I did on the first Mission: Impossible, was to be different. We didn’t have a script at all! That is to say there was no script in pre-production and we would often only be given scenes on the day or a few days prior to shooting a sequence. During pre-production, McQ would call all HoDs to a meeting and tell us the plot and how he saw each scene developing, what stunts were being considered and hopefully, what requirements could be expected of us. Of course, this meant there was also no traditional scheduling. We mostly just worked from a block calendar. Good communication with the director and production would be key to making this work.

My first contribution to this latest episode started in October 2019 when I was already working on Black Widow. I had a message from TC’s team to say that he was in training for a speed-flying sequence that would be featured in the film but that it was not due to start shooting until February 2023. Fortunately, I was about to travel to Atlanta without my UK team so was able to send my 1st AS, Lloyd Dudley, to look after this aspect of pre-production. As always, TC needed communications for this stunt sequence and also as usual, there would be some dialog. Though it is well known that Tom always performs his own stunts, long ago I suggested that giving him dialog during the stunt sequence would also confirm to the audience that this is him and not a stunt double. I have sometimes come to regret that suggestion.

On every Mission: Impossible, the stunts get bigger and seemingly more dangerous though I should say that for Stunt Co-ordinator Wade Eastwood and his team, safety is paramount. As part of the safety requirement is good communications with TC and the stunt team, I decided to utilise the bone conduction technology that I had developed for use in the last Mission: Impossible (Fallout). The system uses custom ear moulds that are both microphones and earpieces. A small conductor is designed to sit on a specific part of the ear to pick up speech with minimal background noise. Though you may imagine speed flying to be near silent as opposed to the helicopter sequences that I had previously used bone conduction for, the wind noise could be quite high and difficult to keep off a conventional microphone. There were also safety considerations that we did not want a lot of loose cables that could interfere with the parachute when deployed. We were now using Audio Ltd. (now Sound Devices) A10 radios in simultaneous transmit and record modes as we are able to do outside of USA. Communications were using digital Motorola radios that gave good long-distance coverage to a base station setup. In conjunction with my long-term technical collaborator, Jim McBride, and his son Mark, custom interfaces were made to integrate both recording and comms systems. Lloyd and Mark spent most of the rest of 2019 with TC on various locations, including the Lake District in UK and in South Africa.

Having finished on Black Widow, I started my prep early in 2020 tech scouting various locations, including Venice where we were due to start shooting. It was on the tech scout that when standing in line for the buffet breakfast with McQ behind a large party of Chinese tourists, who were coughing and sneezing, that McQ remarked, “I’m not going to stay here when we shoot, you don’t know what you’ll catch.” Though it was said as a joke, we both requested to stay in different hotels, though for me, it was to a hotel that I had previously stayed in when shooting Spider-Man: Far from Home, because it had a very good space for equipment storage and better boat access than the typical tourist hotels. It was also in a part of Venice that was away from the tourist areas and a better place to spend several weeks in Venice.

We were a couple of days away from our first shoot day and testing our record function of the A10 radios for a boat sequence. Here, I planned to record on the body-worn A10’s and some well-placed A10’s for sound FX. I had recently been working with Paul Isaacs of Sound Devices to develop conform software so that all the recordings could be conformed to what is shot on camera and available for dailies as a poly wav file. We were testing with stand-ins on the canals when we started to hear in the news about COVID-19 causing some concerns in areas of Northern Italy not far from Venice. It was a matter of days and the day before we were due to start shooting that we were closed down and evacuated back to quarantine in the UK. A small number of the crew had symptoms but were unsure whether it was COVID or the flu and fortunately, no one suffered any serious effects.

We spent the rest of the year up until September expecting to restart as the epidemic grew bigger and more serious. The rest is history for all of us but McQ and TC were very keen to restart production as soon as possible but it was to be six months of downtime.

Before we eventually started back to work in September 2020, I spent some of the downtime looking into communication systems that could allow us to work efficiently whilst maintain social distancing and also that could allow remote working in the event that director, DP, or any of the key crew were forced to isolate. I discovered the BOLERO system from a company called Riedel https://www.riedel.net/en/products-solutions/intercom/bolero-wireless-intercom/.

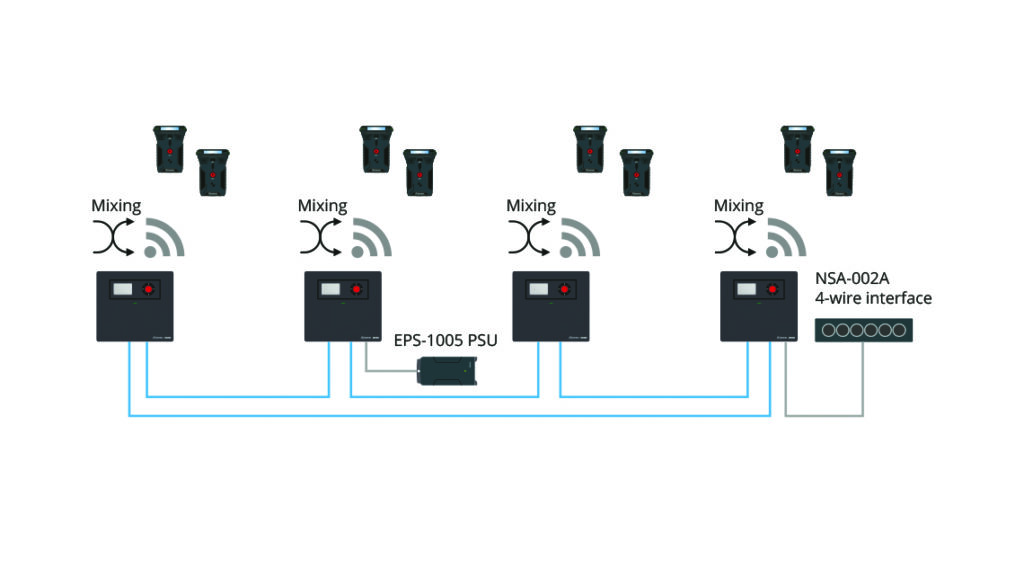

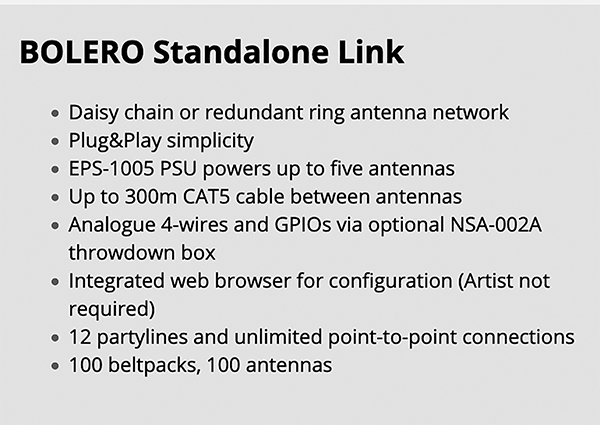

The system was mainly used in F1 motorsport and big sporting events and allowed full duplex communications over large areas. I made contact with Paul Rivens, who ran the Riedel UK Operation. Good news for us was that due to the postponement of the Tokyo Olympics, there were lots of units available. Paul kindly set me up on a training course at Riedel in UK and then set up a demo for production. The producers asked me to specify a system which they then bought. I passed on most of this information to the British Film Institute, who were also investigating ways to get us all working again and many other productions in UK adopted the BOLERO system. We bought twenty-five BOLERO handsets for key HoDs, then integrated with our Motorola walkie-talkies so that everyone could communicate effectively from a safe distance. I also integrated my directors talk-back system and the video assist system and sent production audio to the BOLERO handsets so that there was no need to wear an IEM or to carry a walkie-talkie. A BOLERO antennae typically covers an area the size of a soccer pitch and multiple antennae connected by an Ethernet cable can be used to cover vast areas. I was even able to integrate cellphones when much larger distances needed to be covered, for example, when shooting the car-chase sequences in central Rome.

We restarted production in Norway. The first sequence was shooting the big motorcycle off the mountain stunt that was seen in most of the press and teaser trailers long before the film’s eventual release. Once again using the Bone Conduction Tech to communicate with TC and to record any dialog. We recorded this to a body-worn A10 and to my Scorpio and CL16 main unit cart setup.

COVID was still a big problem, so to create a bubble for the crew and actors, we all stayed on a Hurtigruten cruise ship. This was a brand-new ship that had only just come into service and was now laid up because there were no cruises operating. The beauty of being on the ship in addition to the comfort and great food was that when we needed to move to another location, we did so overnight waking up to the sound of multiple helicopters ready to ferry us to set.

We then stayed in Norway to shoot much of a sequence on trains that involved cast members on the roof of the train carriages and sequences inside the train. The majority of interiors were completed much later in UK in rail carriage sets built on the backlot at Longcross Studios.

Also, in Norway we shot some of the speed-flying and parachute sequences with TC often jumping from a helicopter. The Bone Conduction Tech once again allowed dialog to be recorded, as well as enabling communications with helicopters and cameras.

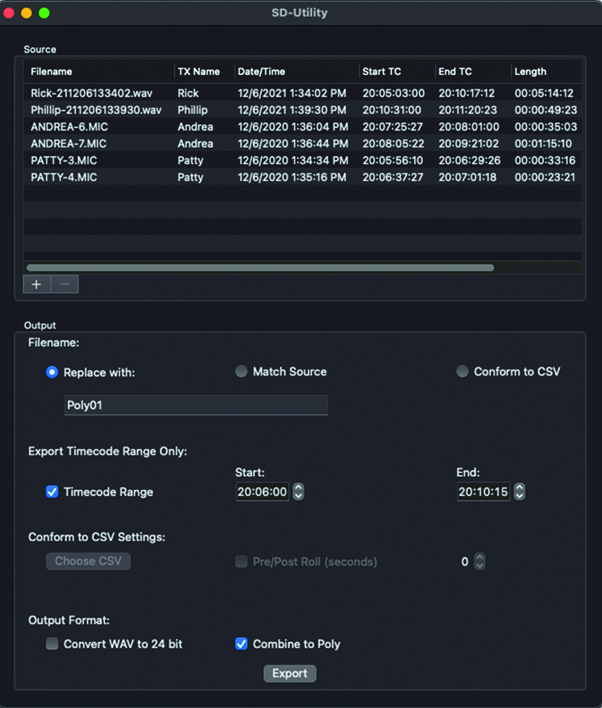

After Norway, we moved to Italy to shoot in Venice and Rome. We shot fairly conventionally in Venice using our BOLERO system for communications which McQ, our director, had fallen in love with, as it allowed him to speak directly to his DP, AD’s, Gaffer, Key Grip, Operators, and to the Voice of God system if necessary. This included a big party sequence in Palazzo Ducale. Boat sequences and chase sequences through the streets and alleys of Venice were shot using body-worn A10 transmitters and the tracks conformed to a poly wav because it was neither possible for us all to be in the boats or for us all to cram into a following boat. The Rome car-chase sequences presented similar issues and employed similar solutions. This sequence has a lot of cars and a lot of dialog. We rigged the cars with A10’s and fitted them to the actors putting everything into record. There were no follow vehicles except when using Russian Arm or similar vehicle-mounted cranes or tracking vehicles. Mostly the cameras were mounted on the action vehicles the director was watching by high-powered video transmitters which were not always in range. I sent guide production audio to the video transmitters and also used cellphones connected to the car hands-free systems to communicate back to the BOLERO system to keep the cars always in communication. When we broke dailies at lunchtime, we did not actually break for lunch as we always work continuous days, I would conform the individual files recorded on the audio A10 and A20 transmitters to a single poly file for the editors. I did the same at the end of the shooting day. As explained earlier, this process is relatively simple. The best way is to leave all of the transmitters in record for as long as possible and not to stop them in between takes. The metadata for slate and take information is entered onto the main recorder, in this case, a Scorpio with a CL16. Even if there was no useable audio, the Scorpio is put into record just to capture the metadata info. Making a sound report in a CSV (Comma-separated Values) format creates an EDL (Edit decision list) that is used to conform all of the individual A10/A20 recordings into poly files for each take ignoring anything recorded between the takes using SD-Utility https://www.sounddevices.com/product/sd-utility/

This means that from an editorial perspective, they receive a single poly file for each take that is similar to what they would expect in conventional shooting. I became very fast at conforming, meaning this did not take up too much time at the end of the day. Of course, it did mean that my team had to be particularly vigilant at timecode synching all of the A10 and A20 radios. It was not until toward the end of production that the Nexus was available which made the whole process much easier. With the Nexus, all transmitters are automatically timecoded and it is possible to remotely stop and start recording on each device, as well as making other changes like file naming, sleeping/unsleeping, changing frequencies, and adjusting power levels. This has been quite a game changer for me since we now set up a network making access to the transmitters possible for any of my team from a phone or iPad.

We had several shutdowns due to COVID but on the whole, probably managed to keep going more than most productions.

After Italy, our next location was Abu Dhabi. The good thing here was that there was already a vaccination program in place for any of the local crew and hotel staff we were likely to come into contact with. However, we were all still unvaccinated as there were as yet no vaccines approved in UK or Europe. We shot primarily in an airport that was under construction and yet to be opened, and for the first time, shot in a fairly conventional manner. We also shot the desert sequences which were tricky to protect so much equipment in what was intended to be a sandstorm. We worked mostly in Land Cruisers that we had fitted out. However, COVID was becoming a real problem in the UK with yet another wave and new strains of the virus being discovered. We had to leave Abu Dhabi before we had shot everything needed because the UK government was about to introduce an isolation program that on our return to the UK would force us to isolate in specific hotels for two weeks. We made it back just in time and eventually rebuilt parts of the airport set in a shopping centre in Birmingham, and the desert sets in a quarry, to complete the sequences.

Most of the remainder of the film was shot on sets at Longcross Studio either on one of the two stages that we had specifically built for us during the COVID shutdown or on the backlot and on UK locations.

It is often said that “Necessity Is the Mother of Invention,” and in this case, the necessity to comply with COVID restrictions forced us to investigate new ways of working. Mainly with a complete change of how we shoot and record car and chase sequences to avoid the crew being jammed into follow vehicles by using the recording capabilities of radio mics and the ability to conform to a single poly file, and as well as the use of duplex communications to avoid having to work too closely together on set enabling us to communicate efficiently.

Certainly, as far as the Mission: Impossible series is concerned, I do not think there will be any going back on the changes we made during the COVID pandemic. We have proved that recording on radio mics, particularly now that the A20 has 32-bit float and SD Utility has the capability of conforming the files for editors, is the way to go. I’m not certain that other productions will continue with the BOLERO communication systems but our director, Christopher McQuarrie, has requested the system to be expanded for Dead Reckoning Part Two which is already in production, though currently on hiatus due to the industrial action taken by writers and actors.

We are already planning how we will record dialog and facilitate communications for some even more daring stunts, including using some new technology to record underwater. Currently, I am not permitted to write about this or the even more amazing stuff that we are doing but look forward to telling you all about it in 2024.

Due to the extended schedule because of COVID, we had a number of different team members for the shoot. These were the following: Lloyd Dudley, 1st AS/Additional Production Mixer; Tom Harrison, 1st AS/Boom Operator; Luigi Pini, 1st AS/Boom Operator (Italy); Freya Clarke, 1st AS/Boom Operator; Hosea Ntaborwa, 1st AS/Boom Operator; Ayesha Breithaupt, 2nd AS.