Mission: Impossible – Fallout marks my second outing in the series and third film with Tom Cruise. I had previously worked on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, but collaborated with a new team for this latest installment. My longstanding colleagues, Steve Finn and Anthony Ortiz, who worked on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, both decided to make the break to mixing. I’m pleased to say both were successful, and hopefully, they learned as much from me as I learned from them in the years we spent together.

by Chris Munro

Previous experience has taught me to expect the unexpected; after all, anything can happen. So, upon starting pre-production, it came as no surprise when one of my first meetings with Tom Cruise was at the London Heliport in Battersea. It took place as Cruise piloted the helicopter that took us to an airfield close to the studios. He explained there was a plan for a helicopter-chase sequence in the film where he needed to be able to pilot the helicopter with no visible headset or helmet. At this stage there was no script, and for some weeks, we worked with Writer/Director/Producer Christopher McQuarrie, verbally explaining the storyline. The Mission films are all about practical stunts and FX so everything has to work in real-life situations.

Fortunately, I have worked on a number of films featuring helicopters and used them as an essential means of reaching challenging locations. The most notable project, Black Hawk Down, garnered me an Academy Award for Best Sound.

I had previously considered using bone conduction technology, most recently on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation for the sequence where Tom Cruise is on the outside of a giant Airbus A400M in flight. The technology has been around for years, but I learned that the military had adopted it, which greatly improved the audio quality. The challenge with older technology is that many of the sounds in speech are made in the mouth and not all transmitted through bone conduction. Without these sounds, speech can sometimes be less intelligible. The research process was quite extensive, as not all information was readily accessible. I eventually came upon a company that was developing bone conduction headsets for commercial use, but the caveat was headsets needed to be custom made. Thus, we needed to arrange for an audiologist to take impressions of Cruise’s ears and create concealed bone conduction headsets specifically for him.

Photo: Chiabella James.

The next stage was to test if and how they would work. I set up four large powered speakers in a studio office and played back helicopter sounds at a level in which you could not hear someone speak. We then invited Tom Cruise to sit in the room with the earpieces fitted and connected to a walkie-talkie. Incidentally, the earpieces also offered a high degree of hearing protection, which would be important for anyone spending hours in a helicopter without a headset. I went outside the room with another walkie-talkie, and we were able to communicate perfectly. With the first stage complete, I now had to work out how the system would function in a helicopter.

At this stage, the model of helicopter had not been determined, though we knew that it would be one made by Airbus Industries. Speaking with Airbus engineers, I established that different helicopters may use different avionics systems, and it was not possible to modify or interfere with these in any way given it may affect airworthiness of the aircraft.

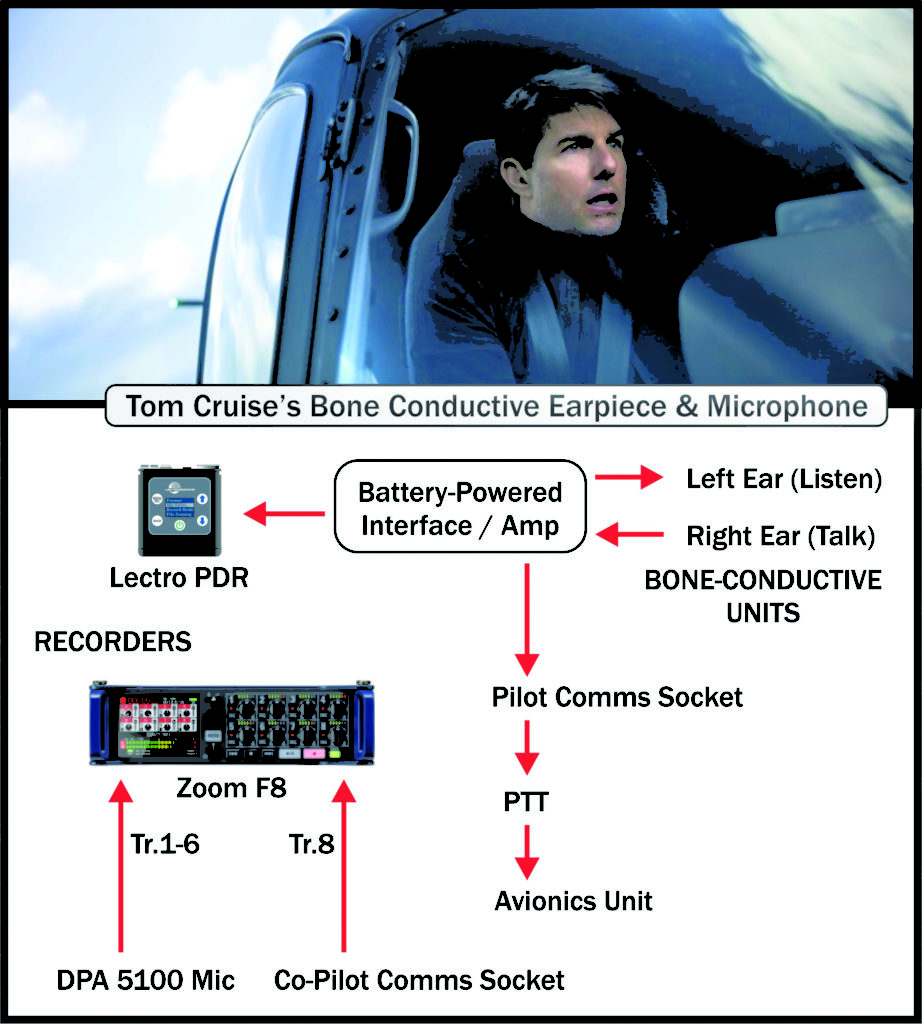

As a result, I called upon long-term collaborator Jim McBride, who has been the technical wizard on many films that I have been involved with in the past such as Black Hawk Down, Gravity, and Captain Phillips. McBride has worked in varying technical capacities on films, as well as in music, and even in a nuclear power station. McBride and I decided we needed to build totally independent self-powered interfaces that were isolated from the helicopter avionics, yet could still use the same PTT (push to talk) button on the helicopter cyclic or control stick.

Once we had prototype interfaces made, we were ready to start testing with helicopters. With the assistance of aeronautical engineers, we went back to Denham Airfield and installed our equipment in a helicopter. Pleased with the results, we sought approval from Tom Cruise and asked him to give it a try. The first thing Tom did before take-off was to call the control tower for a radio check. ATC reported good quality but were suspicious. The controller remarked he didn’t believe we were in a helicopter because it was too clear, as he couldn’t hear any engine or rotor noise. This result was due to the fact we’d used the bone conduction units fitted in Cruise’s ears with minimal pickup of background noise.

The next step was sorting how we would connect to a recorder. The limited space within the helicopter prompted us to find something that could be easily hidden when cameras were fitted.

We originally thought about using a radio link to connect to a hidden multitrack recorder that would also be recording 5.1 FX but wanted to avoid radio transmission within the helicopter if possible. I decided to record to Lectrosonics PDRs which would have timecode sync with cameras and could be easily hidden. We made an output on the helicopter communication interfaces for them to connect to.

Even with production not yet underway, I had put in a substantial contribution to the film. This level of prep was essential for sound efficiency and to ensure all ran smoothly. In some respects, there are similarities to sound design in the theatre, and perhaps a production sound designer would be a more appropriate title considering we no longer mix to a mono or stereo Nagra. The mixing component of our job has become less important; however, our responsibilities have increased proportionately with the advancements in technology.

The helicopter sequences were not at the start of the schedule so we still had a little time to perfect the systems. Shooting began in Paris in April of 2017 at the Grand Palais, with car and motorbike chases throughout central Paris. I was joined by UK assistants Lloyd Dudley and Jim Hok, as well as Paris-based assistant Gautier Isern, who had recently finished working with Mark Weingarten on Dunkirk.

I needed a small multitrack capability at this stage and experimented with the Zoom F8 and the DPA 5100 surround mic which we could easily hide in the BMW M5 cars. Given we had several cars with different camera rigs, their relative low cost made it possible to hide one in every car. We used radio mics on the actors, primarily so that we could record a rushes track for editorial purposes. This also allowed McQ to monitor performances in a follow vehicle. Supervising Sound Editor James Mather, his dialog editors, along with Re-recording Mixer Mike Prestwood Smith, would later decide which of the mics worked best. We also mounted transmitters on various parts of the car exterior with DPA 4160 mics to get sound FX. We followed the chases in a specially adapted high-speed-chase vehicle with antennae mounted for sound and video and remote camera heads. The van was rigged to carry McQ, DP (who also operated a remote head camera), video assist, another camera remote, and 1st ACs. We would chase the cars or motorbikes whist shooting either from cameras mounted on the action vehicles, tracking vehicles, or very often, an electric bike. We always had a team pre-rigging the next car or bike to be used after a shot was complete. Our team rigged mics on every camera tracking vehicle whether it be the Russian Arm, an electric camera bike or ATV. The rear-mounted mics on the cars and bikes were rigged close to the exhausts, while others were mounted close to the engines. I was particularly looking for FX that sounded real, knowing that sound FX editors could use these later as a base to create a much bigger soundscape. I was not always looking for super-clean FX but usually something raw that sounded more documentary style rather than super-clean FX. That said, I did usually try to record clean interior ambiences in 5.1 with the DPA 5100 surround mic.

The Grand Palais sequences were set in a big music event with lasers, light shows, and projected graphics that all had to be in sync, so we worked closely with an AV company to provide audio playback linked to a timeline based on timecode from playback to ensure continuity from shot to shot of graphics, sound, and lighting. Several weeks were spent working in Paris shooting a major action sequence alongside the River Seine. The sequence is where Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) once again meets Soloman Lane (Sean Harris). Sean had previously established that the voice of his character was quiet yet menacing. It was not easy to record during the mayhem of the wild action sequence, but we managed to capture it while retaining his performance.

The following location was in Queenstown on New Zealand South Island where we started with sequences set in a medi-camp prior to shooting helicopter sequences. Steve Harris joined our crew here, as he had worked on several films in New Zealand, thus very familiar with the landscape. Many of our locations required travel by helicopter, so I needed an ultra-small shooting rig that could give me the facilities of my normal rig yet fit easily into a helicopter. I built a rig on one of the larger all-terrain Zuca carts fitted out with a Zoom F8, a custom-built aux output box with the ability to send feeds to video and comms, an IFB transmitter, a Lectrosonics VR field with six radio mic receiver channels powered by a lead acid block battery in the base.

On our first helicopter shooting day, the 1st AD told me with a grin, we would be starting with dialog on the first shot and had dialog to record from Henry Cavill hanging outside a helicopter. Fortunately, I had already taken the precaution of having bone conduction earpieces made for Henry. These were invaluable when connected to a Lectrosonics PDR to record his dialog in flight. I also needed to record sound FX inside the helicopter, and I used the smallest multitrack with timecode that I could find, the Zoom F8. We fixed a DPA 5100 5.1 microphone to the interior roof and hid the F8 under a seat. This was done so if it were caught in camera, the 5100 could look as if it were part of the helicopter. We were able to start/stop and adjust levels on the F8 without needing to access it by using the F8 controller app on an iPhone. Similar to the Paris chase sequences, I wanted the FX to sound real and not like enhanced library recordings. Thus, a little wind on Henry’s mic often added to the reality. Additionally, because the bone conduction units were largely unaffected by background noise, the 5.1 recordings could be useful even if only certain elements of the six tracks would be used.

Tom Cruise always piloted his own helicopter with cameras mounted on it. Director Christopher McQuarrie would fly in another and film from at least one other camera helicopter. Because the helicopters would take off and shoot for at least thirty minutes at a time, Editor Eddie Hamilton asked if I could record McQ’s helicopter comms in addition to what I was recording of Tom and Henry for the takes. This would allow him to align with exactly what McQ was intending for each shot. I used another PDR for this because of the timecode sync capability and small size. At the end of the day, we became data wranglers downloading the various SD cards and making sound reports.

After New Zealand, we returned to the UK to shoot in studio and various London locations, eventually joined by Hosea Ntaborwa. I had mentored Hosea when he was at the National Film and TV School on behalf of BAFTA and Warner Bros. creative talent. This was one of his first jobs after graduating and since then, has become part of my regular team working with us on The Voyage of Dr. Dolittle and Spider-Man: Far from Home. We had some rather challenging locations in London and it was whilst shooting on one of these, Cruise injured his ankle.

The company went on hiatus for a few weeks, which gave me an opportunity to prepare for the HALO jump sequence. That is High Altitude Low Opening and involved Tom Cruise jumping from an aircraft at an altitude high enough to require oxygen. We had a huge wind tunnel built on the backlot in the studio so that the skydive team could plan and practice manoeuvres while

experimenting with camera angles. The wind tunnel was also useful for my first asssistant Lloyd Dudley and I to develop the system for recording Cruise during the jump. We were able to set up communications between the skydive team, McQ, camera operator, and ground safety.

The wind tunnel was incredibly noisy so we were appreciative of the fact that the bone conducting earpieces offered a high degree of hearing protection. The skydive team were amazed that we managed to achieve audible communication in the wind tunnel, which made it much easier to plan shots and make adjustments. The team warned that skydivers have been trying for years to get good recordings during the dives but that they were always battling against wind noise and that it would be impossible to record. I reminded them that this was Mission: Impossible!

When we began shooting again, many of the locations were very inhospitable to sound, but nothing I had not come across before. The team also continued on studio sets at WB studios at Leavesden.

During this time, I continued to prepare for the HALO jump sequence, which was to be shot in Abu Dhabi. We did a number of tests with Cruise and the skydive team jumping from a Cesna Caravan at various UK sites. What we couldn’t test was what would happen at the highest altitudes when oxygen was required, and the jump was from a giant C17 aircraft. I was concerned with safety and that the equipment we were using in both Tom and the skydiver’s helmets was intrinsically safe. The dive helmets contained lighting which could potentially ignite the oxygen, so we arranged for tests to be done in an RAF lab with all of the equipment used for the HALO jump. We also had dialog to record inside the C17 as the jump progressed from a dialog scene directly into the jump. We shot some exteriors of the C17 and interiors on the ground at RAF Brize Norton near Oxford in the UK. This at least gave us a chance to consider what we would be up against.

Eventually, the time came to travel to Abu Dhabi. My crew there was Lloyd Dudley and Hosea Ntaborwa. Lloyd concentrated mainly on looking after Tom Cruise’s bone conduction headsets and fitting Lectrosonics PDR recorders to actors. Hosea was in charge of comms for the skydive team and recording 5.1 FX in the aircraft. I was particularly interested in sounds of breathing and how that can add tension. Once we played some of these sounds for Tom, he immediately wanted it to be a major part of the soundtrack during the jump sequence. I was not looking for pristine recordings that sounded like they were shot in a studio, instead, I was interested in the raw sounds of the helmet mics and bone conducting units which could give a more realistic documentary-type sound. I was not opposed to some wind noise and realised this could add to the reality. Having original sound adds to the feeling of reality even the audience are only subconsciously aware of it. Post production was greatly contracted due to the hiatus in shooting. Supervising Sound Editor James Mather had time restraints, thus appreciated all of the raw sound FX we could give him as elements to enable his team to create the final audio to be mixed by Mike Prestwood Smith. Both have been collaborators of mine on several previous films.

In conclusion, this film involved huge leaps of faith from all parties involved. I greatly appreciate the support from Tom Cruise, Chris McQuarrie, the production team, and my team throughout. My previous experiences, intuition, along with an incredibly well-respected new team proved immensely valuable. Much of the sound was unmonitored being recorded on PDR and hidden recorders. Chris McQuarrie and the producers trusted us to deliver on Mission: Impossible – Fallout using never-before-used technology. Most importantly, Tom Cruise trusted we would develop technology that would allow him to perform stunts efficiently, safely, and wherever possible, avoid ADR in order to enhance the reality.

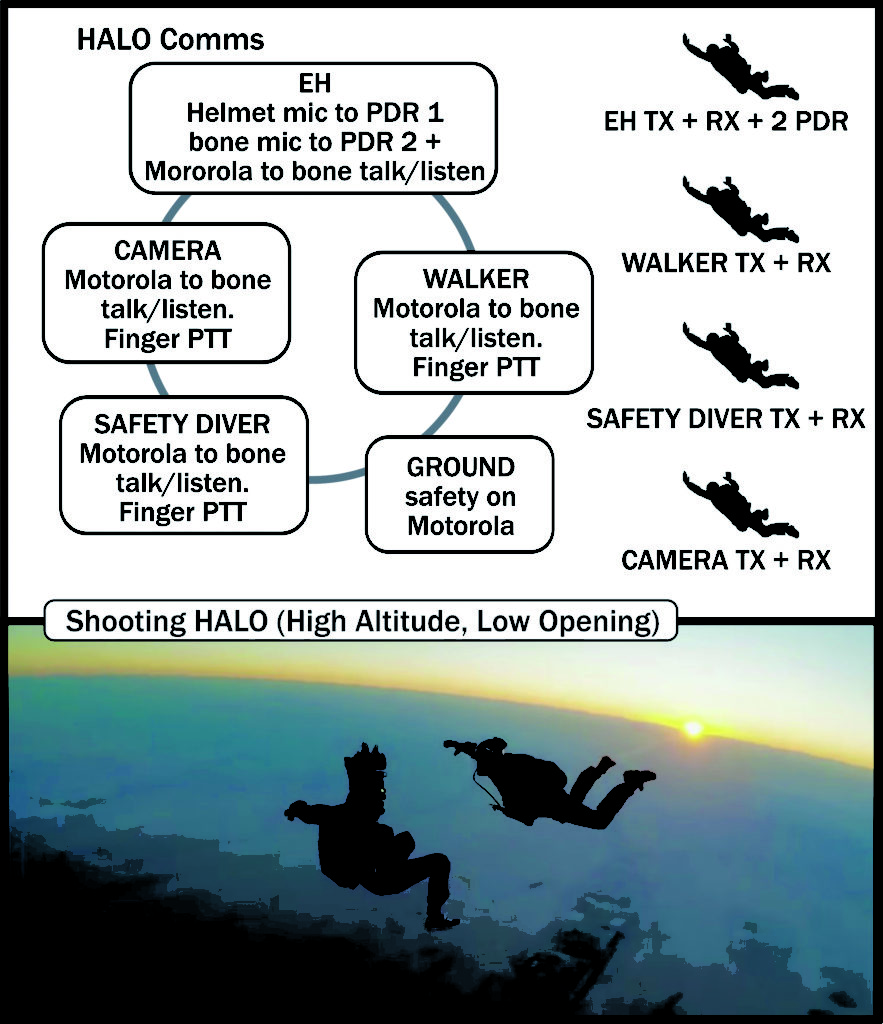

HALO COMMS

The original intention was to use a radio mic TX on TC with a recording facility and have each of the additional divers and camera operator have a receiver connected to helmet-fixed earpieces. When we were safety testing, one of the requests was that we did not transmit anything inside the aircraft but that it was OK to transmit as soon as the divers had exited. I argued that radio mics would be fairly low power and on legal frequencies but then realised that it may have been a mistake to try to achieve recordings and comms with the same device. Additionally, we needed ground contact when the divers reached a lower altitude so that they could be given any safety information about wind or any other issues and radio mic TX may not have enough range.

I decided to use Motorola walkie-talkies for comms mainly because they were reliable and we were familiar with them. We used finger-operated PTT (push to talk) with custom-made interfaces to connect to the Motorolas. The PTT was run inside the sleeve of each diver and operated with a finger and thumb.

For TC (shown as EH on diagram), we used a bone conduction headset in each ear. One ear was talk/listen connected to the Motorola via the PTT and the other ear was connected directly to a Lectrosonics PDR. Another PDR connected to a da-capo mic (Que audio in US?) mounted in the helmet. I chose the da-capo mic mainly because I just happened to have some and also because these are what I had successfully used in helmets on Gravity. I had to send mics for safety testing to be intrinsically safe when used in the helmet, which also had oxygen being pumped in. I immediately thought that the da-capo mics may be well sealed as they are waterproof. It was not a particularly scientific decision.

Tom Cruise’s Bone Conductive Earpieces & Microphone