by Shawn Holden CAS

Imagine my excitement when I was invited on board as the Production Mixer on The Mandalorian, the first-ever live-action Star Wars television show. Now, amplify that when I learned that we’d be shooting with the never-been-done-before technology and techniques for an episodic series. Naturally, I was beyond thrilled to be part of such a groundbreaking shooting experience and the future of filmmaking.

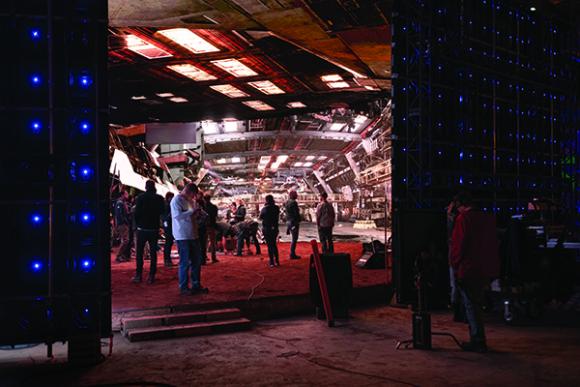

The largest and most sophisticated virtual filmmaking environment of its kind; I’ll always remember that first day stepping into The Volume. With its twenty-feet-high LED screens wrapping two hundred seventy degrees around with two 18×20-foot-wide panels behind the camera that moved in and out of position, creating an almost perfect circle with about a seventy-five-foot-diameter performance space in the middle—topped off with a LED video ceiling.

This technology and the way it was being used allowed the filmmakers to have real-time, photo-realistic effects captured in-camera. It gave us pixel-accurate 3D virtual sets, using powerful gaming and motion-capture technology. The background content would move along with the camera to allow for perfect camera perspective. This was all done with tracking balls on the camera and infrared cameras around the set.

The images that were projected on the LED screens were amazing. A beautiful sunset could be kept at magic hour all day! Maybe a few more clouds passing overhead to reflect in The Mandalorian’s helmet? Just load in a different sky passing over in the LED ceiling.

The Volume was indeed something to see in action, but with all the advantages, came an array of unique sound challenges that we had to address. There was a dot on the floor at the dead-center point of The Volume. In our first meeting during prep, I walked out to this spot with one of our producers, and we started having a conversation to experience the effect that The Volume produced. Speaking to each other at a reasonably low volume, I could hear my voice, amplified, coming from behind me!

It was then that I knew I was going to need some help. I called in a specialist, an acoustical engineer, Hanson Hsu, with Delta H Design. From the center point of the space, he calculated our voices would reflect every two and a half inches around the entire perimeter of the wall at one hundred percent with no decay. Hanson explained that the best solution to allow us to capture usable dialog in this space would be to somehow change the pitch of the LED wall by just a few inches.

Of course, changing the wall’s pitch, the angle of the LED screens, would not be possible. Why? In changing the pitch of the screens, you render the desired effect of the LED’s useless. Working with Hanson, we were able to come up with what we hoped would be a workable solution. He had developed a technology—ZR Acoustics. For our application, ZR Acoustics are screens or devices as Hanson refers to them, measuring four by eight feet, and about an inch and a half thick, weighing just over twenty-five pounds that we hung on rolling stands, vertically. The screens don’t absorb sound or deflect it, rather they take the air that sound travels in and breaks it apart to make the reflecting sound disappear. It’s actually quite remarkable.

The screens could help us provided we could get them placed within four to eight feet of the actors to work correctly, but therein was the challenge. The images that the LED screens were projecting were at times spilling light into the scene. When this was the case we could only use the sceens sparingly between the space where the light was emanating. We also had to be keenly aware of the infrared cameras being used for the camera positioning data. Add to this that we had to be extremely mindful of the potential of the screens reflecting in The Mandalorian’s armor. These challenges were met, gratefully, with a spirit of collaboration, thanks to our DP’s Greig Fraser and Baz Idoine, Jeff Webster, our Gaffer, and the gaming engine crew. When we were able to position the screens where they could best be utilized, knocking down unwanted sound reflections, it allowed us to capture usable dialog in this challenging environment.

It also helped a great deal when practical set pieces were placed within The Volume to break up the reverberant space. Of course, anytime we were shooting inside a spaceship, cabin, or any interior space within The Volume stage, we were able to get great sound.

Shooting in The Volume was not the only challenge. In addition to The Volume, and an additional conventional stage, we used an exterior backlot location. It was an old asphalt lot covered in layers of sand and dirt. Like many exteriors in Los Angeles, this backlot area was enveloped with ambient noise—air traffic, road noise, and train tracks well within earshot. Freight trains would slowly come through, loud, and inevitably stop and idle. Along with the freight trains, a nearby Metrorail train would pass through. The good news was that the Metrorail passing by sounded much like a spaceship coming in for a landing!

The backlot location was mostly utilized for action sequences, stunts, pyro, and shootouts, and less for big dialog scenes. Production was very aware of the challenges of this location and those times when we did have heavier dialog scenes we knew that with luck, cooperation, and coordination from our entire team, we could all get what we needed. But sometimes when things didn’t go our way, you just have to understand that it is what it is and not stress about it. I think anyone ever shooting an exterior dialog scene in Los Angeles knows what I’m talking about.

My crew on the first season of The Mandalorian consisted of Ben Wienert on Boom and Veronica Kahn on Utility duties. I could not have asked for a better sound crew. They both stepped up to the challenges of this show and excelled. It was a pleasure to have them on my team.

This show has its own set of unique challenges when it comes to sound. When watching the series, you may have noticed that our lead character, The Mandalorian, has a very shiny costume. We see absolutely EVERYTHING reflected in it!

Production loves seeing the reflections of the environment rolling by in his helmet or the stars reflecting in his suit as he’s flying through space. There was always a delicate balance of how and where the boom can be placed to stay out of all these reflections, and my team did a fantastic job of doing just that!

When we were able to position the screens where they could best be utilized, knocking down unwanted sound reflections, it allowed us to capture usable dialog in this challenging environment.

Unlike most other episodic television shows, we are fortunate that most of our main characters have one costume that they wear throughout the season. This enables us to build microphones into costumes and leave them in place. We built a microphone and transmitter inside The Mandalorian’s helmet. The first season, he had six different helmets. We built mics into each one so we were always prepared no matter which helmet he would wear. He also usually wears an earwig to hear the other actors, as well as the VOG mic from the director. We have actors in animatronic masks and some with prosthetics that also need the earwig communications to hear direction properly, as well as to hear the other actors. To facilitate communication on our sets, we always have the VOG and speaker set up and ready to go.

I record the show on a Cantar X3 using my Cooper 208 mixing panel. My Boom Operators use Schoeps CMIT’s and a combination of Sanken, DPA, and an occasional Countryman B6 for lavs. When we plant mics, it can be a Schoeps CMC6/41, CMC6/4, or DPA 4098.

As a Production Mixer, The Mandalorian has indeed been an exciting show, and one with unique challenges. I’m proud of our great sound team and an excellent collaboration from our filmmakers and crew. Together as a team, we have all learned so much, and I’m grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to be part of this groundbreaking show, utilizing techniques that I believe will be the future of filmmaking.