by Tod A. Maitland CAS

While that may be true about the visual style of musicals, it is absolutely true about sound. Think back to movies like Singing in the Rain and how they were filmed—big master shots on giant studio stages with brightly lit sets. Compare that to West Side Story (WSS) or tick, tick…BOOM! (TTB) or virtually any of the more recent musicals. Of course, cinematography on musicals has evolved immensely, but it pales in comparison to the transition in sound that has taken place on musicals since as late as the early ’80s.

I was there in those early days (meaning the late ’70s and early ’80s) when practically every musical number was filmed using loudspeaker playback. The only sound that post received from production to fill the speakers’ void was Room Tone. The rest was up to Foley, working hard to make the best of things with a lack of in-sync ambience. Audiences just accepted the “canned” sound of vocals.

Of course, there were exceptions. I remember working with my father, Dennis Maitland, a prolific Production Mixer for forty years who was always on the edge of innovation. For the film The Tempest, he used a very early version of Earwigs to capture live vocals. They were so new, to make them function, you had to run speaker wire around the entire set twice and attach the leads to a powerful amplifier to create an induction loop. Actors/singers had to be inside the loop. Earwig sound quality varied greatly depending on where you were in the loop. It was all very time-intensive. Live songs were a rare breed.

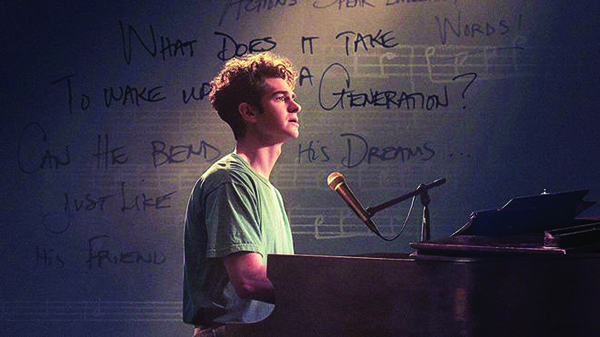

Andrew Garfield as Jonathan Larson in tick, tick…BOOM!

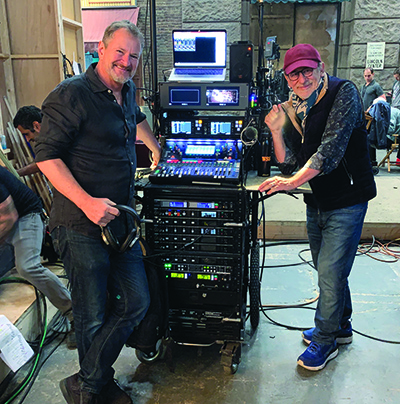

Re-recording mixer Andy Nelson visiting

Tod Maitland on West Side Story

Jerry and Terence walking wireless battery speakers to keep close to Ansel for playback

Today, it’s entirely different. It’s all about creating reality, making musicals sound “natural” and not canned. The days of simply turning on the playback machine on set are over. Paul Hsu (Re-recording Mixer, Supervising Sound Editor, TTB) summed up our goal very well during a recent interview, calling it “hyper-reality.” Musicals live in a real/non-real world. Some songs are recorded live on set, some are prerecorded PB, and many are a mix of both. Our goal is to weave between live singing and PB while maintaining an in-sync ambience, so the audience never knows the difference. But that’s so much easier said than done.

First, a Production Mixer must be equipped with quite a sizeable sound package to accommodate and anticipate everything that can (and will) happen on set. The old saying, “Large package, large rentals,” is true, but being prepared is the name of the game.

Over the last ten years, particularly in the past three, significant advancements in sound technology have made it easier for us to go smaller. Unfortunately, the more compact size hasn’t reduced the price of the equipment or made using it any easier (i.e., every component supports a different operating system!). However, the evolution of our technology has made us more mobile, increasing what we can do exponentially.

Case in point: West Side Story. When I was first offered the film, it was immediately apparent I was way, way underequipped. Recording production sound on WSS was akin to recording a Broadway show on the sweltering summer streets of NYC for seventy-eight days. The enormity of the project alone required us to build a brand-new $300k state-of-the-art sound cart from the ground up, capable of recording thirty channels of wireless inputs, and outputs sent to twenty-four IFB’s and forty Comtek wireless units using seven different mixes. The system also incorporated Earwigs, Thumpers, and wireless playback speaker systems.

Me and Steven at my cart. a lighter moment on one of our few studio days.

Mike Scott booming on West Side Story

The film has massive dialog scenes, and musically, it is a mix of live and prerecorded PB vocals. Many songs required us to prepare for live vocal recording and PB simultaneously. For example, Steven Spielberg would shoot a few takes to PB, then a few takes live with very little time for a sound switchover. As you can imagine, each approach has vastly different needs and requirements. We had to prep for every possible scenario—ready for anything with little room for error.

A typical day on WSS entailed wiring up to 22 actors, swinging 3 booms, hiding up to 4 wireless effects mics, deploying up to 50 earwigs, a Thumper system, and many of our 15 wireless speakers. To further complicate things, NYC has sound restrictions. We overcame this by using a lot of midsize wireless battery-powered speakers placed strategically close within the sets for playback scenes.

The truth was, we needed everything we had for WSS. The dance scene in the gym is a great example. We ringed the gym with our large PB speakers, hid powerful subwoofers in the bleachers for a thump track, earwigged all the primary actors, and wired everyone who vocalized anything. On a film this large, focusing on the singularity of a voice is overshadowed by the need to capture everything!

Jerry Yuen ready for live vocal recording TTB October 2020

Jerry Yuen with two effects mics – 416’s with Shure Axient transmitters on armature wire and sand bags for West Side Story.

Tod Maitland’s preproduction Lav testing booth for Spirited. A 416 and 6 lavs recorded on separate tracks for comparison alignment

The immensity of WSS repeated itself over and over. For ‘Sargeant Krupke,’ we wired and earwigged and boomed everyone. The entire song floats in and out of live and PB. Filming the song, we did Steven’s—a few takes with PB, then a few takes live. When there is so much sound happening in a scene—vocals, natural effects, ambiences, music—sometimes it’s easier for an audience to accept vocals as reality than in an intimate piece. Sometimes not.

Almost everything in WSS is choreographed: from the opening scene where they pass paint cans in time with the music to fight scenes and even dialog. What looks like a simple sound scene becomes another moment for earwigs, effects mics, and soundscape building.

However, a few songs were traditional two-character live vocal records (none without their obstacles, of course). “A Boy Like That” is a classic wireless/boom mix of Maria and Anita as they move through the entire apartment. Their volumes ranged from 0 to 100; I rode the pre-fade volume from -20 to +20 throughout. For “One Hand One Heart,” we acoustically treated the concave ceilings of the church with Sonex to control some of the ambient bounce. “Somewhere” was all about Rita Moreno and her singular voice. In the scene, she started deep in the set, forcing me to start with a wireless (and ambient mic to open up the wireless sound), then switch to a boom when she was close enough.

While WSS needed every bit of my 450-lb cart, tick, tick…BOOM! required far fewer inputs and outputs. Instead, this film demanded a hyper-attention to the singularity of a voice (similar to “Somewhere”), being inside someone’s head, and staying sonically consistent throughout the entire film. In other words, if the quality of the vocal or ambient sound shifts every time prerecorded vocals are used, you lose a piece of your audience.

TTB is filled with examples of how we worked to keep it real. The song “Boho Days” was filmed entirely live without music or click track (which doesn’t happen often). We wired everyone, had three booms covering everything possible, and just let it fly. On the other hand, the scenes inside the theatre that tie the film together were filmed live using the practical SM-58 mics. Anytime there are practical mics, I always try to use them. For these scenes, we kept getting ‘popping’ on the SM-58’s. We stuffed as much windscreen as possible under the mic’s grill and worked hard with the actors on positioning the mics to avoid breath pops.

There were also scenes where we had to pivot our plan and shoot from the hip. One example is when Andrew Garfield sings, “Why” at the Delacorte Theatre. In prerecords, he sang with emotion, but when it came time to shoot, Andrew’s emotional state was far beyond where it was in preproduction. It was obvious we needed to record live. Everyone worked together to make it happen, and Paul in post stitched it together.

Regardless of the size of the musical, the whole process begins in pre-production. This is where some of the most important sound decisions are made. Generally, I start a month before filming and use this time to develop a relationship with everyone who will be integral to what we are doing: Director, Actors, Music, AD’s, Wardrobe, Production Designer, etc. Being the first ‘sound boots’ on the ground, I’m there laying the foundation for sound from prerecords through post.

The first task in creating reality is eliminating the abrupt difference in sound quality from on-set dialog to singing. So, before vocal prerecords begin, I run a series of tests to match every actor to a particular lav mic that best matches the boom mic (different actors sound vastly different on different lavs. We test seven brands with each actor). The chosen lav then accompanies that actor from vocal prerecords through post.

In prerecords, the music mixer adds our boom and lavs to the big fat studio mic, giving post the option to start the song using the same mic I used on set for dialog. I also attend the vocal prerecords, placing mics, and helping actors maintain the scene’s energy—if they’re dancing or emotional in the scene, the sound of that dancing or that emotion needs to carry through.

We approached live singing for WSS and TTB as if we were cutting an album: Microphone placement is always our top priority. It’s everything. We battle hard to place the mics where they need to be. Film sets need to be prepped acoustically. Non-period and extraneous sounds need to be eliminated. Every actor/dancer who needs to hear music for whatever reason gets an earwig and a Thumper for background dancers.

Creating individual mixes for the music department enabled them to listen to live vocals in one ear and prerecorded vocals in the other. This also works very well to keep singers in sync for lip-syncing PB songs.

For big loudspeaker playback scenes where the speakers have obliterated the possibility of recording anything useful: After the company finishes filming the music scene, my team hands out earwigs and IFB’s to all the actors/dancers. They then repeat the entire musical piece as a wild track without singing. Instead, they make all the other sounds they did while filming—dance steps, prop sounds, non-scripted vocalization, and ambiences. We plant effects mics for specific sounds and swing booms at various perspectives to capture a true, in-sync Foley/ambience track.

This wild track is another opportunity to record good FX or ambience. The production sound team are the eyes and ears on set, always scoping for anything in front of or near the camera to record. Another trick we like to slip in for vocals is to record the first line of each song live on set with the same mic used for dialog to help the transition in post.

My crew is everything! Without them, I would be dead in the water. For the last fifteen years, my team has consisted primarily of Jerry Yuen, Mike Scott, and Terence McCormack Maitland. Each of them is amazing and genuinely committed to advancing our level of sound on every film. I’ve been very fortunate to work with this talented team.

In the end, whether we’re recording dialog/vocals on a lav and a boom simultaneously, capturing multi-mic sound effects, Wild tracks, musical Foley tracks, or ambiences, my goal is to give most sound as much variety and as many elements as possible for the mix. It’s no different from any form of art-making; you need a full set of tools to realize your vision.

I believe musicals have become the most complex, challenging, and rewarding films to record. There are so many elements to deal with (and so many personalities to navigate!). In addition, musicals bring out the best collaboration between the production and post-production sound departments. Most films I’ve worked on don’t usually lock in their post sound team until after production. So on musicals, it’s refreshing (and incredibly helpful) to get to talk before filming begins.

I couldn’t be happier with the TTB and WSS final mixes. They are rich, complex, subtle, smooth, and beautiful. But, most of all, they are real (or as real as you can get without filming one hundred percent live and painting out booms). In addition, both films’ music is stunning, adding excellent quality and depth to the overall mix—without overpowering the detail.