HOW I GOT MY GODLIKE REPUTATION PART 1

(A tutorial for those without half a century in the business, and a few with)

by Jim Tanenbaum CAS

There is more than one way to record good production sound, but there are millions of ways not to. Over the years, many fine production mixers have written articles about their guiding philosophies and recording methods.

After rereading mixer Bruce Bisenz’s story in the 695 Quarterly Winter 2015 Issue, now Production Sound & Video, I finally decided to add my 2 dB’s worth. Many good production mixers have elements of their modus operandi in common, and others that are unique to the particular individual. So do I.

Whatever I’m recording: dialog, effects, music, ambience, wild lines—I consider them all just noise. Different kinds of noise to be sure, but when all is said and done, just noise. When I started out back in the late ’60s, I thought my job was to record these noises as accurately as I could so that their playback would sound exactly like the original. Do you remember: “Is it real or is it Memorex?”

I soon learned that that wasn’t such a good idea.

WHAT I HAVE IN COMMON WITH OTHER GOOD MIXERS is (or should be) obvious:

EQUIPMENT

Think about what kind of equipment you’re going to buy when setting up your cart. First, rent one of each possibility and play with them for a week or so. Which unit feels “right”?

In the good old (analog) days, there was basically only one recorder (Nagra), just a few mix panels (Cooper, SELA, Sonosax, Stellavox), and a few radio mikes (Audio Limited, Micron, Swintek, Vega). They were simple, and similar enough that if I got a last-minute call to replace someone, I didn’t have to think twice about using their gear. (Though I did make up and carry adapter cables so I could use my favorite lavs with their transmitters for actors or plant-mike situations.) Now, I have to ask what’s in their package—I would be hopelessly lost with a Cantar.

Sound Devices and Zaxcom both make top-notch recorders. I prefer Zaxcom’s touch-screen Fusion-12 and Deva-24 to any of the scroll-menu CF/SD-card flash-memory recorders by Sound Devices or even Zaxcom’s Nomad and Maxx, but other first-rate mixers feel just the opposite. My brain’s wiring finds the touch screen’s layout more intuitive, and helpful if I suddenly need to do something I don’t do often (or ever).

After you’ve acquired all your gear, you need to spend a great deal of time familiarizing yourself with it. Your hands need to learn how to operate everything without your head having to think about it. Likewise, the connection between your ears and your fingers needs to work without conscious intervention (most of the time). You need to calibrate your ears so you don’t have to watch the level meters constantly because with the new digital or digital-hybrid radio mikes, you can’t tell just by listening when the transmitter battery is getting low, or an actor is getting almost out of range. You have to scan all the receivers’ displays instead, to see the transmitter-battery-life remaining or the RF signal strength. You also need to keep an eye on your video monitors to warn your boom op when he or she is getting too close to the frame line.

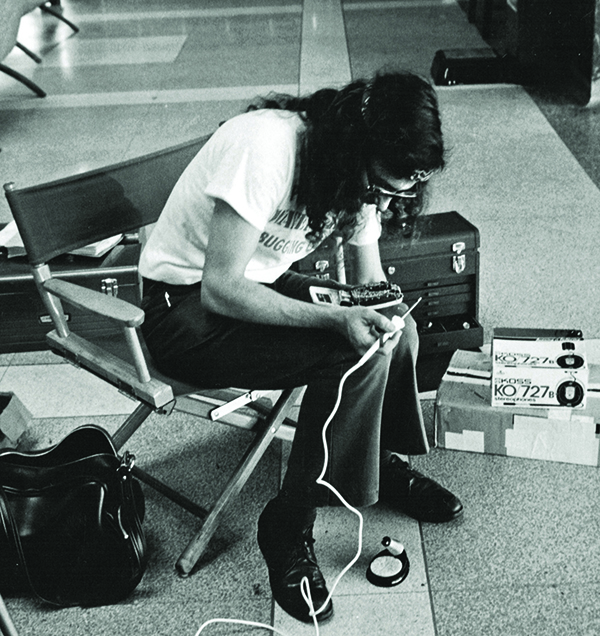

Speaking (or writing, in this case) of your ears, you need to protect them—you can’t do good work without them. For most of my career, I used the old Koss PRO-4A and then PRO-4AA headphones because of their superior isolation of outside noises, so I know if something is on the track or just bleeding through the cups, without having to raise the headphone volume. You should lock off that control at a fixed level, and only change it under very unusual circumstances. If you find yourself straining to hear toward the end of the day and turn up the level, that is a sign of aural fatigue, and an indication that your regular listening level is too high. “Ringing” in your ears is a far more serious warning sign—it may go away, but the damage has already been done. The insidious nature of the damage is that it won’t manifest itself for decades. The PRO-4AA’s air-filled pads fail after a time, and need to be replaced periodically—they either leak or become too stiff. I’ve gone through almost a gross of them and don’t know if I can get any more, but fortunately, there are new headphones available from Remote Audio, which are even more isolating, and I have recently started using them.

Carry a spare for everything, and for “mission critical” items, carry a spare spare. If the original unit fails from an external cause, you may not discover the problem until it happens again while you are investigating. While it is nice to have an exact duplicate for the spare, some very expensive items can be backed up with a lesser device that will do until a proper replacement can be obtained. (The Zoom F8n recorder is a prime example: ten tracks, eight mike/line inputs, timecode, metadata entry … all for less than $1,000. The TASCAM HS-P82 at twice the price is even better if you can afford it.) IMPORTANT: You may need adapter cables to patch the different backup unit into your cart—always pack them with the unit! (And have a spare set of cables.)

Check out all your gear before shooting begins. Were batteries left in a seldom-used unit and have corroded the contacts? Or worse, the circuitry? Is a hard-to-get cable that is “always” stored in the case with a particular piece of equipment missing? This is even more important with rental items.

Have manuals for every unit available on the set at all times. Not only for problems that arise, but also if you need some arcane function you have never used before. PDFs on your laptop are extremely convenient, but a hard copy under the foam lining in the carrying case can be a lifesaver if a problem arises when you can’t get to your computer. (If not the original printed version, be sure that any copy is Xerox or laser-printed, not a water-soluble inkjet copy.)

Don’t forget to research sound carts as well, and at least look at all the different styles at the various dealers’ showrooms. There are vertical and horizontal layouts, enclosed and open construction, different wheel options, etc. Over the years, my preferences have changed several times, first, because of the larger productions I recorded, and later, because of shortcomings I discovered in new situations.

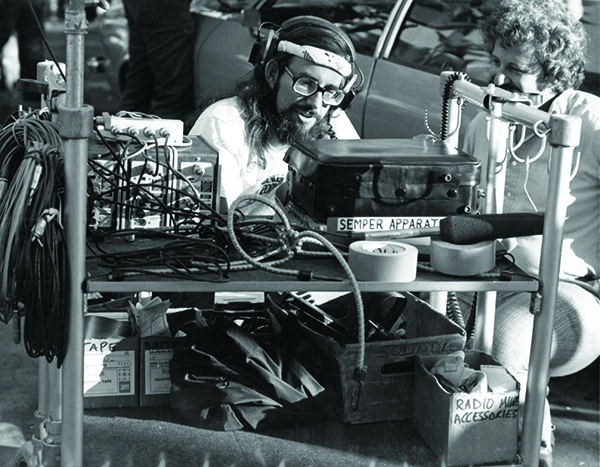

I started with a folding Sears & Roebuck tea cart. It was light and folded flat, which made it easy to store and transport, and set up and wrap quickly. It also let me work in small spaces. Unfortunately, it wasn’t designed for the rigors of production, and the plastic casters broke early on, followed by failure of the spot-welded joints. I replaced the casters with industrial ones, and brazed all the joints. I still use it for some one-man-band shoots. You can see its major deficiency: lack of real estate.

But I liked the concept, so I had a custom cart of the same design manufactured by a company that made airline food-service carts. This solved the lack of space, but created the problem of needing a lot of room to set up shop. It was so big, it had to lay flat on top of all my other gear in the back of my 1976 International Harvester Scout II (an SUV before they were called that). There were also the same problems that I had with my first folding cart: stuff bounced off when moving over rough surfaces; rain, especially coming on suddenly; and having to unpack all the gear in the morning and interconnect it, then having to put everything away at wrap.

My final cart solved all these issues. In 1979, I designed a tall shipping case that had all the equipment built in and permanently connected. All I had to do to set up was remove the front cover and attach the antenna mast assembly. It was narrow enough to fit easily through a 24-inch-wide doorway. The height of the pull-out mix panel allows me to mix while standing (a good idea when car stunts are involved) or seated in a custom-made chair. And I can stand up on the chair’s specially-reinforced foot rest to see over anyone standing in front of me. The cart is completely self-contained, with 105 A-H of SLA batteries. The extra set of tires lets me travel horizontally over rough ground, and the dolly can be unbolted to use separately if needed. The only problem remaining is the 325-pound weight.

Here is a lightweight alternative vertical design belonging to Chinese mixer Cloud Wang. Whatever cart style you choose initially, be prepared to replace it after you have gained some experience, and perhaps again … and again … and…

If you’re going to work out of a bag, rent various rigs, fill the pouch with thirty pounds of exercise weights, and wear it for many hours. Experiment with changing the strap tension, bag mounting height, and all the other variables, including different size carbineers to attach the loads. A hip belt is a necessity to distribute the weight and reduce the pressure on your shoulders. Nothing available worked perfectly for me, so I wound up buying both Porta-Brace and Versa-Flex rigs and creating a Frankenstein from the top of one and the bottom of the other.

The organization of your stuff is Paramount (or Warner or Disney or…) for efficient operation and avoiding errors, especially in stressful situations. I use both colors and numbers, according to the RETMA Standard (which is used for the colored bands on electronic components): 0=Black, 1=Brown, 2=Red, 3=Orange, 4=Yellow, 5=Green, 6=Blue, 7=Violet, 8=Grey, 9=White. My radio mikes and mixer pots are all color-coded, as are all my same-sized equipment cases, which allow my brain’s right side to take some of the load off its left side. Note that I have permanently taped the unused faders on the mixer’s right side, and temporarily taped off the Channel-4 fader of an actor who’s not in the shot, using his label from his radio mike receiver. I also taped over his radio mike receiver’s screen for good measure. I can tape off the faders at the top, full-open position, to keep them out of the way because the Cooper mixer can power off individual channels. I also label the faders with the character names on the front edge of the mixer. I usually don’t have to highlight individual character’s dialog on my script sides, but if I do, I use the same color as their channel. “Constant Consistency Continually” is my motto.

In addition to numbering cases, you need to label their contents somehow, either by category (e.g., “CABLES”) or more detailed contents. Whatever system you decide on, it needs to be intuitive and quickly learned because you may be using different crews from job to job.

I do a lot of my business with one major equipment dealer and rental house, but I make it a point to buy a fair amount of stuff from another company as well. Not only does this keep both of them competitive on prices, but if I’m in the middle of the Sahara Desert and the camel kicks over my sound cart, I’m not limited to what one of them has in stock for immediate replacements. (Not an unrealistic example—in Morocco, my local third person accidently dumped over the sound cart in the street. Fortunately, it was rental gear.) Have you ever tried to set up a high-limit credit account on the spot, over the phone, with a company you’ve never done business with before? (Besides, I get twice as many free T-shirts, hoodies, and baseball caps.)

Don’t neglect to visit smaller dealer/rental houses as well. They may be willing to take more time to help you learn the equipment, or open the store at 3 a.m. Sunday to handle a last-minute emergency.

If you’re just starting out and can’t afford to buy everything at once, rent the recorder and radio mikes. They rent for a smaller fraction of the purchase price and evolve the most rapidly. WARNING: Don’t buy a new model as soon as it comes out—the first few production runs sometimes have problems that require a hardware fix that is expensive or impossible! This happened to me twice—I didn’t learn the first time. My first-run Vega diversity radios were in the shop more than on the set for several years. My first-run StellaDAT was so unreliable, I was happy when it got stolen. Also, if a well-established product suddenly is offered by the manufacturer at a discount, it may be about to be replaced by a new model—this happened to me recently after I bought $8,000-plus of name-brand lavs.

Equipment insurance is as important as the gear itself, but takes an entire article to do the subject justice.

PRE-PRODUCTION

If you don’t know the director, research their shows on IMDb, and watch some of them to get a feel for the director’s style and technique. Talk to people who have worked with her or him.

Read the script as soon as possible, looking for scenes that might have challenges for the Sound Department, or an opportunity for you to make an esthetic contribution to the project.

Speak with the director at the earliest opportunity to discover what his or her feelings are regarding sound and its relation to the project. The director may have sound ideas that are impractical, if not outright impossible, but saying: “I can’t do this,” is always a bad idea. I prefer saying: “It would be even better if you did this instead.” If I can convince the director it was her or his own idea, so much the better, because they will be less likely to fight me later on.

The most important question to ask the director is: “What do you want me to do if there is a sound problem during a take?” (It probably won’t be “Jump up and yell ‘Cut!’”)

The second most important question is: “What do you want me to do if I need an actor to speak up?”

Believe it or not, the “Don’t bother me with sound problems—I’ll loop it,” is by far NOT the worst attitude. If the director doesn’t care about the production sound, that leaves me free to do whatever

I want, so long as I stay out of their way.

The worst type is the director that looks over my shoulder and tells me what to do. Or the producer—fortunately, I found out about him before I accepted the job (to replace their “bad” mixer) and turned it down. The show lasted five more miserable (for sound) episodes before it was cancelled—I talked to the replacement mixer afterward. If I find myself stuck with one of these shoots, I ask the director either: “Why did you hire me if you wanted to mix the show yourself?” or as many questions as I can think of about every shot, even when the director doesn’t come over to my cart first. This results in either: A, my being fired; or B, being left alone for the rest of the shoot. So far, I haven’t been fired.

If you are not familiar with the DP, gaffer, and/or key cast members, research their attitudes toward sound by interviewing other mixers who have worked with them. (Search IMDb for the info.)

If you can’t get any of your regular crew people, be careful about accepting recommendations from other mixers. Be particularly skeptical if they won’t or can’t tell you what the person’s weaknesses or shortcomings are—everyone has some. And personalities are important—a detail-oriented utility person may be perfectly compatible with one mixer but annoying to another. (Again, this isn’t a made-up situation. I did a TV pilot with a “highly- recommended” 3rd person that turned out to not know how to do anything “my way,” and took a very long learning curve to get up to speed.

Even crew you have used before need to be vetted if they haven’t worked for you recently. They may have changed their styles from working for other mixers, or just been away from the business for several years.

Go on all the location scouts. (Of course, you should make every effort to convince the production company that your presence there will be worth far more than what they pay you.)

I know that when I see a practical location next to an automotive tire and brake shop and under the LAX flight pattern, the UPM will respond to my request for an alternate venue with: “The director likes the look, it’s easy to get the trucks in and out, and the rent is cheap.”

Why I do go is to get a head start on solving the sound problems I find, so that on the day I will have what I need. For example, a courtyard with a dozen splashing fountains may need two-hundred square- feet of “hog’s hair” and a hundred bricks to support it just above the water’s surface, and this is not likely to be available at a moment’s notice from the Special Effects Department.

PRODUCTION

If they are being used on the show, go to the dailies (“rushes” for those of you on the East Coast) whenever possible. Besides the possibility of getting you a free meal, you will have a chance to judge your work without the distractions of recording it. I find it usually sounds better than I remember it—if it sounds worse (though still “good enough”), I need to find out why. Also, if someone questions some aspect of the production track, I am there to explain it before the Sound Department gets blamed for something that wasn’t its fault—a bad transfer, for example.

Sadly, the pace of modern production often eliminates screening the footage in a proper theater for the director and keys on a regular basis—the director and DP have to look at a DVD or flash drive of the shots on a video monitor between setups—when they can spare the time. Still, attend this if you can.

Make friends with the Teamsters early on. When they come around to get used batteries for their kids’ toys, give them a box of new ones instead. Then, if you need the genny moved farther away, they will be more cooperative, especially if you tell them as soon as you get to the set.

Make friends with the electricians early on. When they come around to get used batteries for their kids’ toys, give them a box of new ones instead. Then, if you need the genny moved farther away, they will be more cooperative in stringing the additional cable, especially if you tell them as soon as you get to the set.

Make friends with the grips early on. When they come around to get used batteries for their kids’ toys, give them a box of new ones instead. Then, when you need a ladder for your boom op, or a courtesy flag to shade your sound cart… Ditto for props, wardrobe, and all the other departments.

WHAT I DON’T HAVE IN COMMON WITH OTHER MIXERS isn’t obvious:

EQUIPMENT

Many mixers require their equipment to “earn its keep.” They won’t buy a piece of gear that they may never (or seldom) use. I have a different philosophy: if there is a gadget that will do something that nothing else I have will do, that is reason enough to acquire it. (And one element of my godlike reputation.) Some examples:

1. I have several bi-directional (Figure-8) boom mikes and lavaliers, even though they are not commonly used in production dialog recording (except for M-S, which itself is rarely needed). But their direction of minimum sensitivity (at 90º off-axis) has a much deeper notch than cardioids, super-/hyper-cardioid, or shotguns. On just two occasions in over half a century, they have allowed me to get “good enough” sound under seemingly impossible conditions. The US Postmaster General was standing on the loading dock of the Los Angeles Main Post Office while surrounded by swarming trucks and forklifts and shouting employees, which completely drowned out his voice on the omni lav. I replaced it with a Countryman Isomax bi-directional lavalier, oriented with the lobes pointing up and down. This aimed the null between them horizontally 360° and reduced the vehicle noise to the correct proportion to match the visuals. Since we didn’t see his feet, I was able to have him stand on a pile of sound blankets to help deaden the pickup from the rear, downward-facing lobe. (Of course, afterward, the director asked, “Why don’t you use that mike all the time?” Then I had to explain about all types of directional mikes’ sensitivity to clothing and handling noise and wind.)

2. I also have a small, battery-operated noise gate. While not suitable for use during production recording because the adjustment of the multiple parameters requires repeated trials, it has enabled me to make “field-expedient” modifications to an already-recorded track. I cleaned up a Q-track so a foreign actor wouldn’t be distracted by boom-box music and birds in the background while he looped it on location before flying back to his home country. I removed some low-level traffic that was disturbing a “know-nothing, worry-wort” client on a commercial shoot and earned the undying gratitude of the director, who knew that it wasn’t a problem but couldn’t convince the client. (I also was able to close-mike some birds in the back yard and add them to cover the “dead air” between the words.)

3. Every time I find bulk mike cable in a color I don’t already have, I buy 50 feet and make up a 3-pin XLR cable. This allows me to hide them “in plain sight” by snaking them through grass (various shades of green), or running them along the side of a house where the wall meets the ground (various shades of brown for dirt and fifty shades of gray for concrete or asphalt). Wireless links have all but eliminated the need for cables, but in the rare case where they are needed…

I read many trade magazines, and investigate any new piece of gear to see what it will do. I offer to beta-test equipment, like the Zaxcom Deva I or the Lightwave Cuemaster. I soon bought production models of both of them, and still use the Deva I (upgraded to a Deva II) for playback of music and the prerecorded side of telephone conversations. I had Rabbit Audio upgrade my Cuemaster, too. Boom op Cindy Gess used the beta on Babylon 5: The Gathering, where a walk-and-talk in a narrow aisle reversed direction while she was behind the camera the entire shot. The mike had to be almost horizontal to avoid footsteps on the plywood-supposed-to-be-metal floor, and swivel 180° to track the actors. I don’t need it often, but when I do…

I know that the mike doesn’t always have to be pointed directly at the actor’s mouth. Good cardioid (and super-/hyper-cardioid) mikes have an acceptance angle of about ±45° from the front where the sound of dialog won’t be audibly affected when shown in the theater. This allows my boom op to orient the mike so that its minimum sensitivity direction is aimed at a noise source and still gets the actor’s voice acceptably. Have the boom op adjust the mike to minimize the noise and then see if they can get the actor within its 90° acceptance cone.

Text and pictures ©2019 by James Tanenbaum, all rights reserved.

Editors’ note: Article continues with Part 2 of 3 in our Summer edition.