by George Flores CAS

I never would’ve imagined that a television show I day-played on almost twenty years ago would still be going. And, I never would’ve imagined I’d currently be sitting in its production mixer’s chair. Frankly, I never imagined still having quite this much fun recording audio. To consider myself lucky is an understatement. That show is NCIS; the original one-hour flagship that has spun off a few other versions over the years.

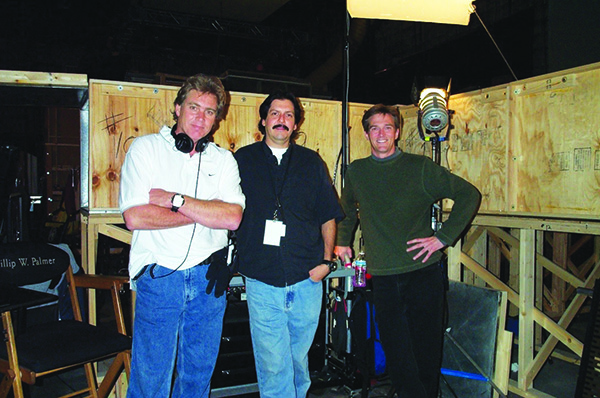

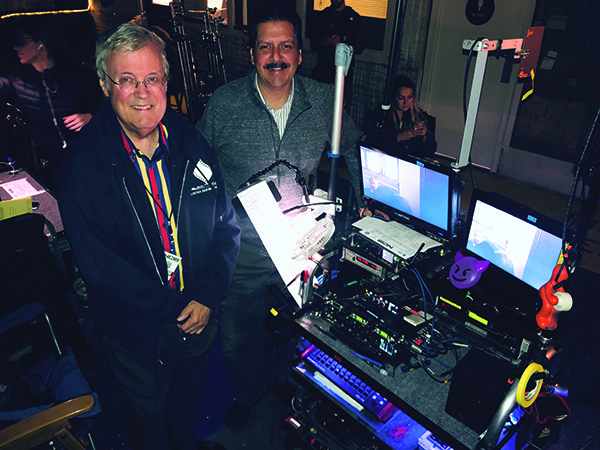

Back in 2003 when the show first began, Sound Mixer Kenn Fuller was at the helm. Kenny’s Boom Operator Dirk Stout and Sound Utility/Boom Jaya Jayaraja did that first season. I came in a few times to utility, working their Saturday units and helping out on the set to set live A/V feed, which is still done today. The second season, Sound Mixer Steve Bowerman arrived with Boom Op Tom Thoms (1950-2020) and Utility/Boom Jeffrey Hefner. I became one of their go-to’s, working on everything from the audio playback, to sitting in Steve’s chair to second and double-up units. Currently, my team is Boom Operator Gail Carroll-Coe and Utility/Boom Jeffrey Hefner. Season 19 of NCIS is completed, and we are scheduled to return for a Season 20. Not a typical run by any means, and I do feel my journey to here is a combination of positive persistence, a handful of luck, and mentorship along the way.

When I was a kid, I was addicted to television and fascinated with recording music and interview programs off the radio. Voices, catch-phrases, and songs that repeated again and again via TV reruns, Top 40/rock radio, coupled with feature films you’d sometimes see in a theater multiple times (and later watch on television), gave my Generation X a cultural signpost of not the greatest era, but the most quotable. This fits right in with my chosen field, which is essentially listening to and documenting words. The words that come from performers may not be all that significant on the day, but they may have an impact to someone experiencing those words & actions months or even years later. This was woven into my childhood psyche, so how can I not seek to be a part of it, this strange sonic environment.

I feel I had this need to belong somehow in this sonic community. I wasn’t great at math and science, wasn’t much of a musician, and I certainly was not an extrovert or performer in any way. However, I did understand there was a connection between the creative and technical processes, where you couldn’t have one without the other. In a roundabout way, I hooked onto that idea of being in these two different worlds which lead me to film and TV.

Growing up in Southern California offered a huge choice of options to study and apprentice. My father, who primarily was a middle school electric shop teacher, also did Local 40 electric work for the movie studios. That was his summer job; had that been on my radar, I could’ve easily wound up as a Studio Electrician. While attending junior college, my first real audio job was with a childhood friend whose father-in-law owned a videography business. I cut my teeth on audio-signal flow, making crude A/V snakes, miking up wedding bands, and shoving interview mics in the faces of Bar Mitzvah guests. I was also a gopher at a small recording studio, which was a great experience, because I got to learn about basic microphone and recording techniques, more advanced signal flow, and that recording “was a business,” which depended on bookings and payments for services rendered. Everyone there had advice to give and opinions to share.

The Audio Maintenance Tech told me about music recording programs and schools in the area and recommended a few to me. The least expensive option was a music degree at a state university, and I chose a small school in my own backyard of Los Angeles, Cal State University Dominguez Hills. The term “Recording Arts” is more defined these days with certain aspects and levels of instruction. Although this was a music engineering program, it felt very comfortable. When I enrolled at Dominguez, I studied both traditional analog engineering and early digital recording. Digital audio recording was just beginning to be written about academically, and there wasn’t room to study audio for cinematic applications. We rarely discussed sound for film or post sound, yet I was able to apply much of it later when I worked on set. The theory was also immediately met with practice, because the school had a small 24-track recording studio within the Music Department. All the audio students had lab projects to record, so you would invariably work on each other’s assignments, or help record concert recitals in one of the theaters located below the studio.

When I graduated in 1991, the home recording market was taking off and computer technology was “bit-by-bit,” changing the way society was doing things. Recording studio facilities were facing an upheaval of technological change, not unlike the film industry would go through a few years later. My options seemed limited at the time but were far from it; the film biz was the perfect place to grow roots, I just didn’t know it at the time. After a mini-career as a temp employee, and doing video work on the weekends, one of the Video Camera Operators I’d been working with said to me, “Y’know, you’d make a good Boom Op,” and I asked, “What’s a Boom Op?” He said, “Y’know, they hold the mic on movie sets. Those union sound guys make a lot of money too.” So, I thought, I’ll check it out, it can’t be that difficult?

Difficult: yes. Impossible: no. It was not easy. Due to the fact I didn’t have any real set experience, it was challenging to initially break in. Part of the job on any set is trust. Your producers and directors need that from the crew. As a subordinate Boom Operator or Sound Utility, the Sound Mixer needs to trust you to carry out the tasks in getting good audio. I had plenty of audio theory under my belt, but next to none when it came to applying it to movies and television. In a nutshell, I had to gain the trust of people that were going to hire me. That trust factor needs to be built over time, working within a department/group, or gaining enough experience to bring that tool wherever you go. Like pretty much everybody who works in the film business, I got experience on low-budget films. “Trial by fire” booming, mixing student projects, and frequenting the vendors, such as Coffey Sound (now Trew Audio) and Audio Services (now Location Sound) were also part of my immersion. When you start out, you tend to work on different jobs with different people. I did like the variety, and every job was a learning experience. Many of the people that I worked with early on are still working today: Ben Patrick, Peter Devlin, Felipe “Flip” Borrero, Richard Lightstone, Glenn Berkovitz, and Susan Moore-Chong. I can’t omit the Boom Operators I worked under, like Thomas Cunliffe, Kevin Cerchiai, Gabriel Cubos (d. 2009), Albert Aquino (d. 2012), and Scott Warren. Each of them has had an impact on my initial audio career that I value to this day.

I worked as a Y-8/Y-7A pretty much when I entered Local 695 in 1995. Beginning around 2005, I got my first long-term mixing gig from another mentor, Steve Nelson. From there, I began doing 2nd unit work, small referral jobs, and fill-ins. Fill-in work is great because you’re placed in a veritable hot seat where you must adapt to the technical surroundings and people. Some Boom Operators are particular about their mic and headphone levels and some Sound Utilities don’t need you to do their job for them. So, when you sit in someone’s chair, you don’t want to go mucking up things. I absorbed a great deal just observing someone’s workspace and their equipment; even trivial things like how sound reports were filled out and timecode numbers were written down. Even where the sound cart is parked is important to remember, because some Sound Mixers want to be away from the immediate set while others want to be close enough to speak with the Director or hold court.

During this time, I also began to purchase gear in earnest. By then I was married, and those decisions needed to be discussed or negotiated. My wife is in the same business (costumes), so she understood that it was going to be a substantial and ongoing investment. I wasn’t going to get all the toys I wanted all the time, yet I didn’t want that either. The mixers I had worked under gave me valued advice regarding what equipment to purchase or when to rent instead of buy. Many times, it wasn’t about the gear, it was about getting the job and establishing or continuing relationships. A Sound Mixer I had worked with, Vince Garcia, had a great old-school talent for making producers comfortable and maintaining a positive attitude that was infectious. He was not a technical sound person at all but was always busy, artfully booking the next thing while on the current show. No doubt about it, positivity does play a big role in working in this business. But I really did enjoy maneuvering in these two worlds, the creative and technical. I enjoy talking about gear and throughout my first ten years of booming and utility, I got an understanding of what I wanted to buy, and what would best work for me. I also had to keep in mind that technology does move forward. The minute you buy a piece of equipment, it can depreciate the moment you take it out of the box.

I entered the industry when film cameras were still being used. A Nagra with timecode was the standard recorder at that time; DAT machines were prevalent, but multitrack hard disk recording was nonexistent. To be around for this digital revolution, like my college experience, seems quaint in hindsight, but there was a lot at stake, especially on the camera end. Visually, you needed a lot more processing power to get proper resolutions in your cameras and that would take a while to fine-tune. For audio, it was a relatively quick A/D conversion, with digital audiotape bridging the gap until hard disk recording really became feasible around 1999-2001 and post-production supporting it. It was only a matter of time before we had multitrack hard disk recorders, so I focused on purchasing certain types of gear: cart power and distribution, some wireless and lavaliers, slates, along with continuing to make my gear sizeable enough to fit in the trunk of my car for all the day-play gigs.

In 2008, I went to work on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. Season 4 of this half-hour comedy was my entry to “Fun Stress.” You’re either going to be completely miserable on a project or you’re not; you embrace the complexities and the challenges or find a way to rationalize your commitment to that project. It was fun having to problem-solve the requests from our actor/creators of this show. Elaborate costumes to wire, live musical performances, stratospheric SPL’s, food fights, blood, and high-octane company moves were some of the challenges. Sunny began in 2005 and had established a system of shooting with three prosumer HD cameras, so I came in really determined to record every microphone on its own track. Along with two (sometimes three) booms, every actor/speaking part got a radio mic. That continued all the way to Season 14, until I segued over to NCIS in 2018.

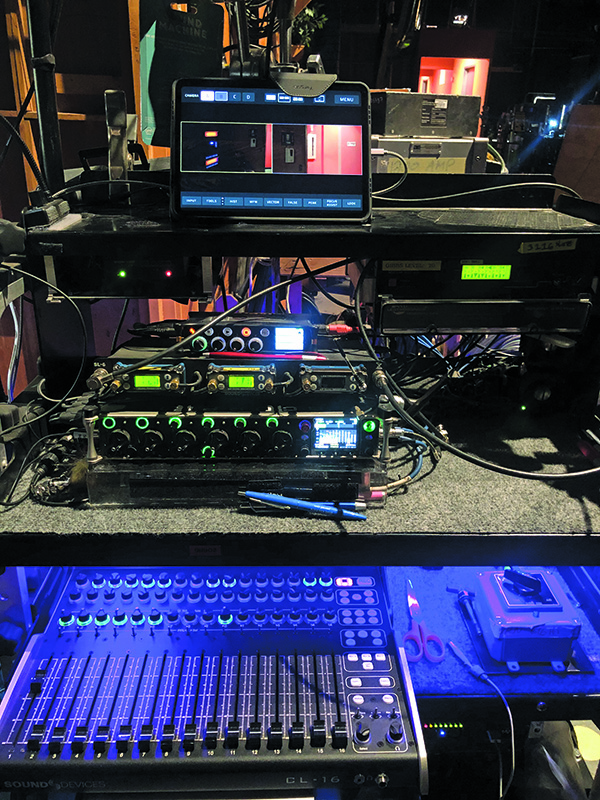

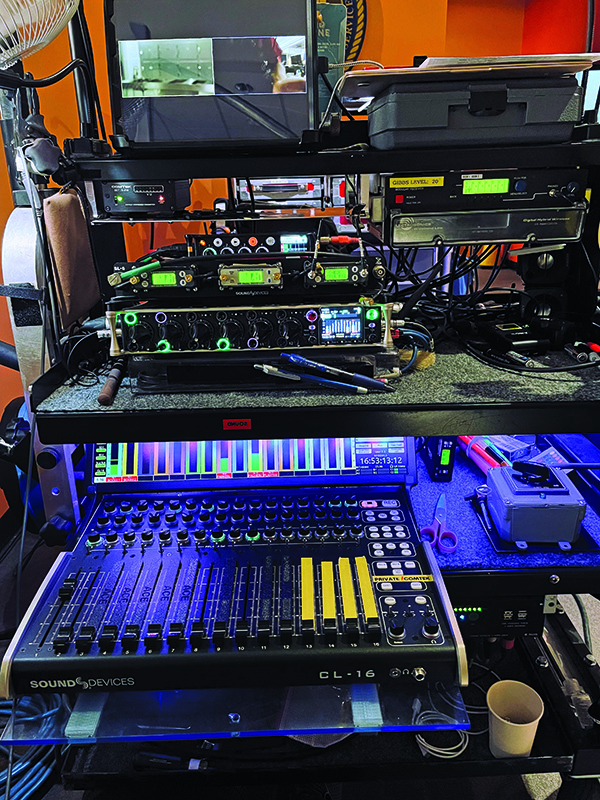

In early 2018, Steve Bowerman who had been the Sound Mixer on NCIS since 2004, decided he was going to retire at the end of that season and asked if I was interested in taking over for him. I told him it would be an honor to continue with his team of Boom Operator Mike Reardon and Utility/Boom Jeffrey Hefner. I had been there enough times as a day player and on other shows to understand that production on an hour episodic can sometimes dominate your life. It’s a constant flow of breaking down a script, execution of that script and schedule, receiving the next script, and repeating that process. I knew however, it was a very good show to work on; extremely experienced producers, writers and directors, and a very efficient crew. The show is an investigative procedural, so we don’t get many elaborate audio requests. That gives my team and I time to work the booms in and dial in wires. These days, I’m recording onto a Sound Devices Scorpio with Lectrosonics and Shure wireless. The Sennheiser MKH 50’s are my choice for interiors. I like its warmth and the low-end punch you can get with close-ups. When we’re outside, we’ll use the Schoeps CMIT. Our current batch of lavaliers we use are the Sanken Cos-11’s and DPA 4000 and 6000 series. With the amount of dialog that is written for a show like this, it can really wear out your ears, but it’s even harder on your team who are out there physically swinging the booms, wiring, or quieting noises on the set. That’s why I try to maintain the positive attitude. As Department Head, you must be a good coach and empathetic sounding board.

To consider myself lucky to be where I am today is an understatement. The timing and good fortune I’ve had is really underwritten by the joy of working on set. Having the ability to straddle this creative and technical world, and learning from extremely talented people. I still maintain that desire to get to work in the morning, to be excited about the people there, and playing with the audio toys. It doesn’t get much better than that!