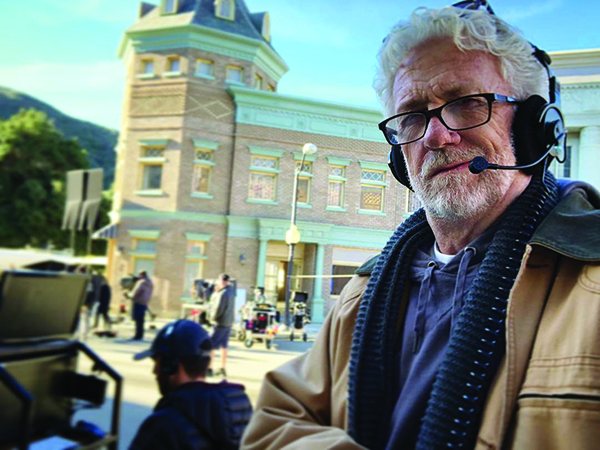

My Life as a Commercial Sound Mixer

by Crew ChamberlainI

My name is Crew Chamberlain, yes, that is my real name, ever since the spring of 1952 when I was born in Fullerton, Calif., at the edge of what we now call the “Thirty Mile Zone,” a child of the baby boom, as well as a fourth-generation Californian, from a large family that settled in and around Orange County. Many of them worked the “Oil Patch” for the Standard Oil Company, others had their own businesses, but not one of them worked in Hollywood or even knew someone who did. Media back then was a black-and-white television (five stations), radio (lots of stations), and a Saturday-afternoon trip to the Fox Fullerton to see the latest double feature for thirty-five cents.

As much as I loved the films and TV that I grew up with, it never occurred to me that there was a system of people, places, and companies that made the content I consumed. We just loved the grand and silly movies like Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Nutty Professor, The Great Escape, or TV shows like The Twilight Zone and The Man From U.N.C.L.E.. I was totally oblivious to the process of film production. That started changing in high school where I was a proud C student. I only enjoyed having fun, playing drums in my garage band, body surfing, drawing, or painting.

In my sophomore year at Sunny Hills High School, an art teacher gave our class a unique assignment. She had us paint patterns on exposed 16mm film (a clear strip) which we then projected in class and played songs to. We all liked this so much we asked to do it again and again. She next suggested if we could get access to an 8mm camera, we could try and make a short film. We did and it was terrible. Not a Spielberg in the bunch, but we had a blast doing it. That little spark started a slow smoldering interest of film within me. With parental pressure to go to college, the Vietnam War spinning out of control, and a very motivational mandatory draft, I discovered that there was a thing called “Film School.” Not the ubiquitous film schools of today, at the time there were only three: NYU, UCLA, and USC. It took me a year at ASU to get my grades up, but with some hustle and a lot of luck, I got into the USC School of Cinema in 1971. I had found my calling.

The USC Film School was a nerdy endeavor in the eyes of the student body back then, until the release of American Graffiti by fellow Cinema School alum George Lucas during my second year. All of a sudden, everyone knew and thought highly of our little dilapidated barn and stable complex on the corner of campus. What a deep dive I took. We lived, breathed, and endlessly discussed cinema. I watched at least two films a day from every genre and era. A very talented group of professors like Mel Sloan, Ken Miura, and Drew Casper engaged and enlightened us. We had to make many films, write a screenplay, and learn the nuts and bolts of the gear. Film cameras! Sound recording on Nagras with microphones! History & criticism!

Editing … sweet editing. A filmmaker’s last chance to make a story into something. That hands-on creativity is what I loved the most. That was going to be my choice of career path after college. I would become an editor and of course, some day a director….

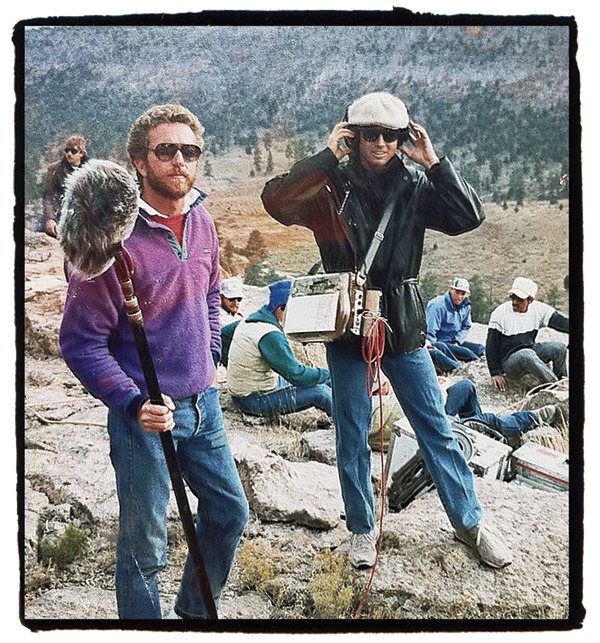

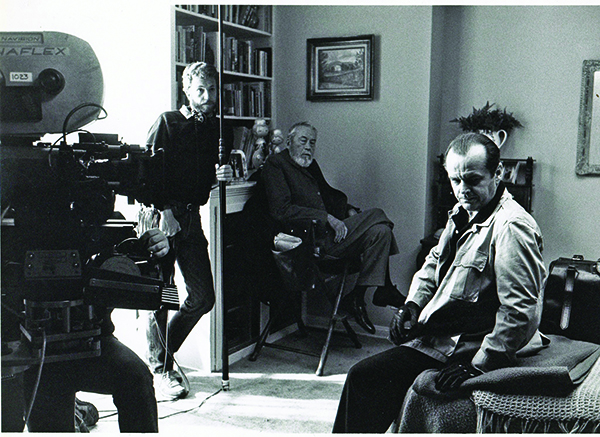

After USC, I landed a job at Wexler Films (not related to Haskell or Jeff) that made medical and health-related shorts for high school education departments. I was an ‘assistant editor,’ but really a PA. On shoot days, I did everything needed, including the sound recording for interviews on a Nagra 4L with a 415 or Sony ECM 50 lavs. I loved production shoot days and these interactions lead to other sound gigs. Soon I was sound recording on docs, interviews, and low-budget films. I also started booming for other mixers which seemed very natural to me as I had the coordination and enough sound knowledge to get it going. Looking back, the progression was a steady one. I went from working on drive-in-level Corman films, to a John Cassavetes movie (Opening Night), to Albert Brooks’ first film (Real Life).

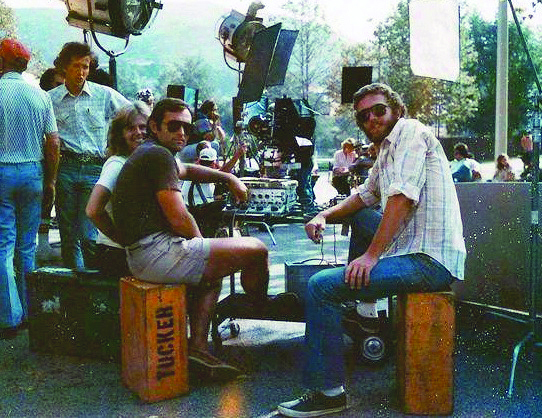

For the first thirteen years of my career, I pursued films above all else and landed some good ones. I was fortunate to get better and better movies and experience with some of the best mixers of the day, Jeff Wexler, Jim Webb, Art Rochester, and Keith Wester. Between all the films that I did, I boomed for many good commercial mixers, but mostly Roger Daniel. As much as I appreciated the work, I wasn’t a fan of commercial shoots. No one whoever went to film school wanted to do commercials.

Films were the goal and I did about as well as possible thanks to Jeff Wexler and Don Coufal mentoring me. Thankfully, Roger continued to hire me between films and showed me many of the valuable aspects to commercials that I had overlooked. Like the time/money ratio.

It all came into focus for me in 1986. I was thirty-five years old with a wife and two kids under five years old that I loved and I wasn’t able to be a full-time father and husband for. That year, I was on location for nine of the prior twelve months. I took a good long look around, I felt good about where I’d been and all I had learned and decided that a change was needed and my path forward was going to be in the commercial realm. At least until the kids grew up, I consoled myself.

Commercials. Yep, commercials. Still hard to believe. When I got in the IATSE in 1977, film was the undisputed king of the crop. Television was a different beast than today, closer to the old factory system of the studios that were cranking out a steady stream of cop shows or three-camera sitcoms, and commercials were, well, commercials. The stigma was understandable as commercials were formulaic and square at best. That all started changing in the mid-’80s as a new sensibility and atheistic took hold. Directors like Joe Pytka, Ridley and Tony Scott, Rick Levine, Bob Giraldi, Adrian Lyne and others brought a cinematic look and approach to the process. An entertaining thirty- or sixty-second movie/story was the new direction. These directors all did commercials, as well as the emerging music videos and feature films. For them, work was work. Another day to practice and perfect their craft was the sensibility. Money was a motivator too. The commercial stigma started to evaporate a bit.

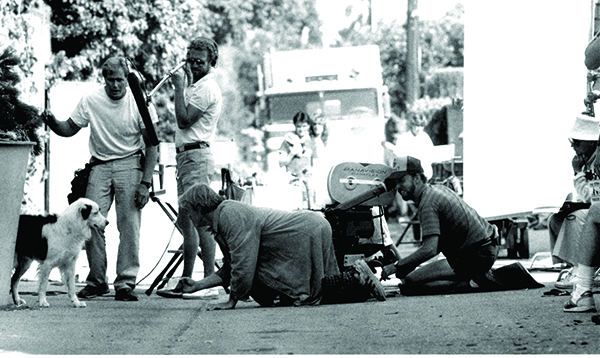

For a Sound Man (that’s what we were called and mostly were back then), the commercial work left the two walled sets on quiet stages and more often ventured out to practical locations where the challenges were more difficult, exactly like film and TV. The work was still ninety percent one boom and a mono Nagra and luckily one camera, so our success rate was high. Roger and I did so well that I was working more days a year than I had prior, but the big difference being I was home every night with my family. I was happy and seldom looked back. On commercial shoots back then, many a day was short for the Sound Department. We’d have a later call, record our part, and go home early. A lot of six- to eight-hour days in the eighties and early nineties. The glory days as it were.

Roger had a very loyal clientele of the top players in the commercial world, the LA, NYC, and London production companies and directors called him first. I nicknamed a lot of people and I called Roger “The Godfather.” Not that original but true. He handed off many, many gigs to other mixers. I and others benefited greatly from him doing this to keep his customers satisfied. That’s how I moved up to mixing in late 1987. I started covering for Roger on the weekends when Pytka would fly a small group up to Santa Rosa to do “Bartles & Jaymes” commercials. Simple shoots: A Nagra, a 415, and a radio mic. Only one of the two actors spoke. As much as I loved booming, the handwriting was on the wall and by the end of 1988, I bought two used Nagra 4.2’s and a stereo Sela from 20th Century Fox, a Lectro Quad Box with 195’s in it and six Comteks. I already owned two Schoeps MK 41’s. So there I was, a Commercial Mixer.

Hard to believe it was ever that simple. I continued to cover for Roger most of the time but I soon got new clients of my own.

We were working nonstop and I learned so much about being a team leader because Roger was my sign post and guru. As a mixer, I rely on my boom ops to run the set and I run the gear, get the calls, baby-sit the production people, agency, and clients. I have been fortunate to have so much help from my boom op friends when I started, pros like Steve Bowerman, Randy Johnson, Jim Stuebe, Mychael Smith, later with Pam Raklewicz, Dan Kent, my brother Moe, Alenka Pavlin, Anna Delanzo, Peter Commans, Bryan Whooley, and for the last eighteen years, my niece Marydixie Kirkpatrick. My two sons Case and Cole even boom for me now and again as they are up to speed in our unique world of production sound recording for picture. With that kind of help, it has been easy and fun to do my end of the job all these years. I want two qualities in a teammate, a good work ethic and the ability to find the humor each and every day in the absurd work we do. These women and men are all champs in this regard and I owe them my successful career. While we had some killer days, it never seemed like work, always an adventure.

The work. It is really no different technically than film or TV. This is as true in today’s multitrack workflow as it was with a mono Nagra and a boom, maybe a radio or two. The biggest difference between long form or episodic media creation and the thirty-second epic is that sound is a two-person department 99.9 percent of the time. To do our job successfully, we have to pull together to get whatever needs doing done so that “waiting on sound” is never heard. The division of labor is equal, running/wrapping cable, putting down sound blankets, etc. We have to be ahead of the curve as much as possible. On any given day, the cooperation with other departments gets limited due to the time constraints on all of us, so when help is needed, we have to request it early when it can be accommodated, not after we set up a shot. This is true for all the departments in commercial production. With only a storyboard and a few confused conversations with an often overwhelmed production manager, we all show up at a location with sixty-five other craftspeople and make a commercial. We work not only for the director (like films and TV), but also the ten to twenty agency people and clients.

This aspect of the work is what took me a long time to come to terms with. Often these fine people have little or no filmmaking experience or just enough to be dangerous. If you let it, this fact alone will make your life hard, perhaps joyless. Communication is essential in our commercial world as we try to put their fears to rest and assure them it will be great. Then we tear it down and do it all again the next day with a different crew and for a different director and client in some high-rise or on nasty a pig farm. Like our brothers and sisters in TV and film, we work at every location imaginable. Hot or cold, often both in the same fourteen- to eighteen-hour day, as we do our best to make it sound like it looks. It still surprises me that this system works as well as it does.

Our simple workflows of the eighties and nineties have all transformed into the new modern work style of multi-camera shoots, with all sorts of rigs to move cameras everywhere, and no money and time to do what is on a storyboard, so sadly we have even less discipline and protocol than before and therefore, sound wires them all to their own tracks as we try to create useful mixes for the director, agency, and the editor in post production. Still, we do this with a two-person Sound Department, even though it would be a full day for three people.

The key for my team is the ability to look two, three steps ahead of what we read on paper and are told by production and actively stay evolved on set, and then have the gear to do almost anything that comes our way. What starts as one woman talking on the phone can morph into a car-to-car shot with four people singing a song as they drive down the road with a video village bus trailing along with always helpful suggestions. In my experience, this wouldn’t happen in TV or film without advanced warning, permits, and sides. Not so in commercials. When it happens and it will, the response “I can’t” is not an option as far as I’ve ever seen. Somehow we need to make it happen. Our video assist brothers know this all too well. They deal with unrealistic expectations and demands all the time. We help each other. I’ve always been there for them as they have been there for me. It’s been an education to have witnessed the introduction of video assist in the late seventies and the evolution into the modern-day NLE-based multi-cam systems we have today. Really a remarkable group of people who made this happen like John Hill, all the Cogswells, the Hawks, Willow Jenkins, Tom Myrick and his gang, and Cal Evans who makes it fun regardless the shoot.

I know for many, the uncertainties of the day in the commercial world can be stressful but whether it is a personal defect or talent in me, I really like what I do. I may work twenty days in a row, then have fifteen days off. I can always say I’m booked if I’m called for a rap music night shoot in Palmdale. I always try to pass any job I can’t or won’t do to a member of my close network but I have little control where production will go after calling me.

Some in production want a known person to do the sound, others just want to cut a deal and sadly, there are those in our community who think low balling on rates and gear is a smart move. There are a lot of sound people in LA, so the competition is always there and at times, adversarial and short-sighted by a few, but most of our community is on the up and up and play by the unwritten rule that we never actively try and steal an account if a job comes to us from another mixer or undercut their rate.

My favorite aspect of working on commercials is the people we get to work with as they pass through our arena, be they the “Hot” new cinematographer, or the old “Pro” you’ve known for thirty years and their talented crews. Also, the energetic young women and men just starting their careers in Art, Hair, Wardrobe, and Production Departments who are fun to be around and prove that hope springs eternal. The athletes and stars can be fun but for me, the crews are the best part of the job. Ageism, while very real in the workforce in general, seems less so for a mixer. At sixty-six, I am often a decade or two older than most of those I work with. I enjoy the energy and modern culture they expose me to and for those who are interested, the sound and production knowledge I’m able to pass on to them.

While it would be impossible for someone to follow my career path today, that world is long gone and the future of commercials seems destined to a slow demise, as the world of new media is expanding, I do think a rewarding career can be had. Hopefully, the lessons of the past might be helpful for those going forward in what we call Hollywood. At some point in the next four years, I will hang up my headphones and get out of the way. I will do so knowing I met and worked alongside many of the most interesting and talented people in the film business and had a lot of fun doing so. And for the record, I do direct, shoot, and edit personal media projects so I guess my original game plan worked. Just not the way I thought it would.