Bond 25: (Part 1)

by Simon Hayes AMPS CAS

The story starts in 1977 when I was seven years old. My father took me to the cinema to see The Spy Who Loved Me. Enthralled by the world of the secret service and the suave and debonair hero who loved cars and gadgets, I was sold. The deal was done when the Lotus Esprit turned into a submarine in the beautifully clear Caribbean, and then drove out onto the beach. I was hooked, from that moment.

I would watch the Bond movies in the cinema at every opportunity even when they were re-run on television, and each time I watched, I became more interested in the character and the franchise. When I eventually got a job in the film industry, it was my absolute aim to work on a Bond film. This was cemented during my time as an ‘in house runner’ (PA) at a commercials production company, as a teenager. I can remember clearly the respect for the crew members they were trying to book for a commercial by the Producers and Directors, when they were not available because “they’re on the Bond.” The more time I spent on film sets, the more I would be exposed to stories being told during camera turnarounds, lighting setups, or at lunchtime by crew members waxing lyrical about “when we were on the Bond.”

During my childhood, I built the franchise up to be one of the pinnacles of filmmaking. When I arrived in the industry, I realised that working on a Bond film was seen as a badge of honour; a sign that a technician was at the top of their game. And, boy—did I want be one of those technicians.

Fast-forward thirty years and I found myself booked for a Bond movie. Not just any Bond movie either; this was to be Daniel Craig’s last outing in the role, on the twenty-fifth Bond film. My crew and I had worked with Daniel on the film Layer Cake before he was cast as Bond, and we really enjoyed working with him. Daniel is a perfectionist, and knowing how hard he works and how much he values production sound, made me more excited about the project. We have an easy rapport which extends to my team, especially Arthur Fenn, my Key 1st Assistant Sound, who gets on extremely well with Daniel. I knew based on our previous experience that working with Daniel was going to be a pleasure. As so many of you reading this will know, if the star of the show respects and collaborates with the Sound Department, then the rest of the cast generally will follow suit.

I was invited to the offices of Eon Productions in Mayfair, London, an imposing building in the heart of the city. The production team wanted me to meet Cary Fukunaga; it is always quite intriguing meeting a director for the first time. To get myself up to speed, I watched a bunch of Cary’s work to learn his shooting style, and how he uses production sound. I was super-excited on how little ADR there seemed to be in his films. When I arrived, I was warmly welcomed by Producer Chris Brigham and invited to join Cary, as well as Producers Michael G. Wilson and Gregg Wilson. There was an ease to the conversation as soon as we started, and it became clear how interested everyone around the table was about sound, not only production sound, but theatre sound systems, home Hi-Fi, Dolby Atmos; it was literally like talking to other Sound Mixers. Cary asked me if I’d ever recorded on a Nagra. I told him that I was fortunate enough to have spent my first six years mixing on a Nagra, on hundreds of commercials, starting on a IV-S that I had converted to timecode when I’d saved up enough money. Cary looked excited and asked if I still had one, Gregg Wilson cut in saying, “I’ve got a Nagra, I adore them.” Michael G. Wilson talked about the Swiss workmanship, at this point I knew I was sitting at a very special table full of real film audio enthusiasts. I told Cary I still had my Nagra at home on display, and he said, “We have a flashback sequence on the film that I’d really like you to record on a Nagra to give it an old school feel.” I told him how interesting I found that, and that I’d also like to run my Deva 24, alongside the Nagra to give him a choice in post. I explained that perhaps when he listens to the Nagra through a modern digital theatre system, he may feel the analog sound is too old school. However, if he wished, he could use the Nagra as a reference, and treat the Deva digital recordings with a plugin to give them the warmth of the Nagra analog recording, but not going quite as far with the analog tape hiss. Cary said that is exactly how he likes to work—he wants choices in Post. I agreed, that is exactly my preference too: give the Director, Supervising Sound Editor, Dialog Editor, and Re-recording Mixer options to choose from. I am completely aware that the way a scene reads in a script may change completely once in picture editorial, and being locked into one specific production sound workflow can be limiting and irritating. As Production Sound Mixers record a scene, we cannot know, how loud the score is going to play or how the Director and Picture Editor may intercut the scene with others, to match dialog perspectives. Cary and myself were speaking exactly the same language, and a burgeoning relationship was developing.

Cary told me that some of the situations were going to be tough, as he wanted to use IMAX cameras for significant sequences during the film. He explained that he was aware they were noisy but he was also pretty sure the dialog on those scenes was going to be minimal, as they were mainly action and stunt sequences. I spoke to him about signal to noise, and how I would try to achieve dialog recordings on the IMAX sequences that would hopefully not need ADR. Cary doesn’t like to use ADR for technical reasons and if at all possible, he’d like to use the production dialog on the IMAX scenes, which would generally be loud sequences with the cast shouting. They would have a lot of FX and score laid underneath which we both felt would help to hide the IMAX camera noise without having to go too far with noise reduction in post. We spoke at length about the Schoeps Super CMIT’s I like to use when recording scenes where there is a lot of background noise, and he was impressed when I explained I would be recording two tracks from each boom mic; the processed signal with 10db off-axis noise reduction and the unprocessed signal with the usual 4db off-axis reduction of a standard CMIT microphone.

Director Cary Fukunaga, Linus Sandgren, DP, and Simon Hayes

Arthur Fenn, Key 1st AS, and Simon

Ben getting the DB5’s ready for a wildtrack

Cary and the producers said that they’d like me to run some tests with the IMAX cameras that could be listened to by Supervising Sound Editor Oliver Tarney, so he could assess the camera noise, treat it with some different de-noising plugins, and see what could be achieved. It was a great idea and it would be really helpful for all of us to know exactly what the limits were in terms of proximity of the camera to the dialog, booms versus lavaliers and how each source would react to the de-noising. Cary said when Oliver had worked on the dialog, we could reconvene and listen to the results in a viewing theatre.

When I left the Eon building, I felt like I’d had a really collaborative meeting with filmmakers who deeply care about sound, and wanted to preserve the all-important original performances. I knew we were at a great starting point and rather than seeing the IMAX camera noise issue as a negative, I started planning how I could minimise the issue and make it work for Cary and our cast.

We set up a test where we ran dialog on exteriors and interiors, on different boom positions, and performance levels from whispers to shouts. For the exteriors, we used Schoeps Super CMIT’s and DPA 4061 lavaliers. On the interiors we tested my preferred interior boom mic, the Schoeps CMC6 and MK41 hyper cardioid.

The IMAX camera was loud, but I know that de-noising technology has really come on leaps and bounds in recent years, and what I needed to deliver to Oliver and his sound post team was a good signal (dialog) to noise (camera) ratio. The greater the ratio, the more ability they would have of successfully cleaning and preserving the original performances. I also knew that a Bond film is generally going to have a driving score and loud sound effects that would help the process of hiding the unwanted camera noise, and the de-noising process would not need to be too aggressive.

After Oliver received the tests, I spoke to him at length where he explained that the camera noise was filterable but only under certain parameters. The dialog needed to be a close perspective; whether that be the boom in close-up, or the lavalier didn’t really matter. This ruled out the possibility for a boom to be used in a mid-shot or wide position. In those instances, Oliver and his Dialog Editor, Becki Ponting, would use the lavalier as it had better signal to noise for the cleanup. We also discovered that the Schoeps Super CMIT should be used on interiors, as well as exteriors if we were shooting IMAX, as the wider pick up pattern of the Schoeps CMC6/MK41 was unsuitable for reducing the camera noise enough, even in a close-up position. Whenever we were shooting IMAX, we would be using the Super CMIT’s and DPA 4061 or DPA 6061 lavaliers to give sound post the best chance of cleaning the recordings. The Super CMIT’s supplied both processed and unprocessed channels, which gave Oliver and his team choices; rather than a ‘one size fits all’ approach, and they would decide which channel to use in every situation and scene.

At the viewing theatre at Pinewood Studios, Linus Sandgren, Cary’s wonderful DP, joined us to listen to the tests so he could get a handle on how the noise of the IMAX would impact the performances. Cary’s 1st Assistant Director, Jon Mallard, was also present who would become an extremely strong ally of the Sound Department. Linus and Jon were absolute gentlemen, really enthusiastic collaborative filmmakers, who treated everything we did throughout the movie as team work.

After listening to Oliver’s cleaned-up tracks, it was evident to Cary that the IMAX could work for action sequences that would have loud dialog and a driving score. For softer level drama, we would shoot 35mm film and for larger set pieces, stunt work, and chase/fight sequences, we would shoot IMAX. We all left the theatre confident we had found a workable solution without too much compromise and that we could go ahead and use the IMAX cameras in certain conditions, without having to commit the scenes to ADR.

The next item on my agenda was to start to plan a workflow for lavaliers with Arthur, my Key 1st AS, who is a first-class boom operator and also manages the lavaliers and places them on the cast. A number of years ago, Arthur took on this role when we started shooting multi-cameras and we realised that the boom wasn’t going to be able to be prioritised in every scene. He has become an absolutely excellent radio mic technician who has an ease and ability to interact with the cast members with a very comfortable and confident charm. If you saw Arthur on a set without his boom pole, only his headphones would give away his role in the Sound Department. He carries a bag on his shoulder, with needle, thread, safety pins, and double-sided tape, giving the impression that he is a member of the costume department, and that is exactly how he behaves around the actors.

When we previously worked with Daniel, we were shooting single camera, and were at the stage in our filmmaking careers where it was possible to use lavaliers sparingly, as two booms could pretty much cover anything a single camera could throw at us. Arthur and I remembered that Daniel is very particular about how the transmitters can create problems in the way his fitted suits hang on the body if the placement of the pack isn’t specifically planned in advance. We also knew that Daniel likes his tie knots to be uncompromised so he can have them in the fashion that the particular suit he is wearing demands. This was very important because of the amount of time Bond spends wearing a suit. Based on this we knew, we needed to reduce the size of the pack and lavaliers Daniel would wear. We decided that Bond would always be rigged with the newly available and absolutely tiny DPA 6061. Having used the 6061 on a couple of movies, I was happy that its small size would not compromise its ability to deliver extremely rich and clear dialog. As far as I am concerned, it is just as good as my go-to lavalier, the DPA 4061. I could use 4061’s on other cast members who didn’t have such difficult costumes and that the two different mics could be mixed and intercut seamlessly. The really great factor with the 6061 was that we could fit one in Bond’s tie knot without it being seen and not compromising the type of tie knot appropriate for the style of suit Bond was wearing. Even a really modern, slim tie knot could have a 6061 hidden inside it invisibly.

We then started to discuss his radio pack. I generally use Lectrosonics for several reasons; first, the build quality is just phenomenal—if a pack gets dropped, it survives, and I have never had a pack fail from a fall. Second, all of my crew have the Lectrosonics app, LectroRM on their cellphones, and are adept at quickly changing gain settings when I ask them over our sound crew comms. We start with a base level on a rehearsal, or sometimes the first Take, after which, I start fine-tuning the gain settings, increasing three or 4dB for whisperers. It is rare for us to reduce gain as my base level setting is one that is impossible for the human voice to cause a square wave regardless of how loud they shout. This is assisted by the limiter in the Lectrosonics transmitters but also that I’m quite conservative with my base-level setting. As I manipulate the gains, I try to achieve a setting that won’t be so high that it engages the limiter on loud parts of the dialog. I try to record without any limiters through the whole recording chain, preferring to deliver raw, uncompressed dialog to Sound Post, so that Re-recording Mixer Paul Massey can choose to use compression later, based on how the dialog will play when mixed with the score and sound effects. I try to use enough headroom to minimise the limiter kicking in.

Our go-to radio packs are Lectrosonics SMB’s, which are really small. However, to really show Daniel we were pulling out all the stops, myself and Arthur decided to dedicate the tiny, super-micro Lectrosonics SSM to Bond full time. We generally only use the SSM for specific costumes (bathing suits, bikinis, ball dresses, etc.) as there is a slight compromise in output power and battery life. However, because I knew Arthur has a great relationship with Daniel if we needed to change battery at a difficult moment, it would be cool.

Obviously, that was never our intention, but the SMB will do a whole morning until lunch, whereas the SSM runs out about thirty minutes earlier. With the ability to ‘sleep’ the radio pack using the cellphone app, we knew that Arthur would be powering down Daniel’s pack wherever possible. This would not only give Daniel confidence he had privacy when not on set, but also increase the period between battery changes. Arthur would talk to Daniel before rigging the costume and find out whether he wanted an ankle pack, calf pack, in the small of his back, or hidden in his jacket. Daniel could base his decision on the action he was required to do, rather than where a ‘bulge’ would be less visible, because the SSM simply didn’t cause bulges in the costume. There were times when we asked Daniel to wear two radio mics, especially when he was in military webbing, because of severe head turns in action sequences, and clothing rustle the webbing can create. This generally happens on one side of the body but not the other, meaning that if radio one had a rustle on it, radio two on the other side of Bond’s chest was clean. Each mic was assigned their own track on the Zaxcom Deva 24. We didn’t overuse this strategy. Daniel was being very generous in letting us use two mics, and we didn’t want him to think it was a ‘belt and braces’ situation, so we only asked when we felt we really needed it, explaining why, and Daniel kindly accommodated the request.

The rest of the cast were assigned Lectrosonics SMB transmitters and DPA 4061 mics unless there was a specific costume that required an SSM and a 6061; for instance, Ana De Armas’s stunning ball dress.

Robin Johnson, my other 1st Assistant Sound, is responsible for frequency mapping all the radio mics and comms, so he assigned a general plan that would allow me to run twenty radio mics at all times, only having to adjust and fine-tune specific frequencies if we had issues on location. We were actually incredibly fortunate that during the making of No Time to Die in Norway, Italy, Jamaica, and the UK, we didn’t come up against any negative frequency situations, and apart from a few minor tweaks, our frequency plot remained the same throughout the film.

Vehicles are a huge part of what makes a Bond movie. Oliver Tarney asked me how I was planning to mic up the vehicles and I was happy to use whatever workflow he preferred. Whatever he asked me to do on main unit, I would also ask our Second Unit Sound Mixer, Tom Barrow, to mirror. Oliver asked for a stereo pair of lavaliers on the exhaust region of the cars that were being featured in each scene. He also asked that we use ‘spot mics’ (lavaliers) on any other parts of the vehicle that we felt gave interesting sounds. We would generally try to place a lav in the engine bay and then think about other unique sound effects the particular vehicle would give us. In Jamaica, Bond was driving an old school Land Rover, so it was the gear shift that had an old, grinding sound to it which I thought would mix well with the stereo exhaust tracks and the engine bay track, to wrap the theatre audience acoustically in exactly what it sounds like to be driving one. This was how we treated each vehicle—find the stereo sweet spot on the exhaust and then add spot mics to pick up the other effects that would build a unique sound of each vehicle.

I knew on No Time to Die we were going to come up against some huge SPL’s for extended periods, as a lot of the vehicles were highly tuned and would be driving at high speeds with tire squeal, etc. There was also a bunch of motorcycles to consider. This motivated me to buy some specific lavs for the job. As I am extremely happy with the famous DPA frequency response—i.e., pretty much flat from 20Hz to 20kHz—and I wanted to stick with the brand I knew and trusted, but I wanted to know I had the headroom to cope with anything, so I purchased some DPA 4062 lavaliers. These are acoustically the same as our favourite 4061, but give another whole 10dB of headroom, with the max SPL a huge 154dB. As soon as we tested them, I knew they were a great addition to the kit. They could be mounted very close to sound sources to make the effects we were recording clean of other unwanted noise, and were virtually impossible to square wave. These 4062’s became our ‘vehicle kit.’ Tom Barrow and our second unit sound team did the same.

We were ready to start shooting. We had been through each scene formulating a creative plan for our approach to the sound recording, and then putting together a technical plan to help us achieve our creative aims. The first week would be a pre-shoot in Norway, shooting the flashback scenes. This meant I needed to get my old Nagra IV-S TC from its display in my screening room at home, and check it was still working. It was, and just putting batteries in it, and loading a roll of quarter-inch tape had me reminiscing about the start of my career. The texture of the alloy case and the feeling of the record lever in my hand were so wonderful to feel again. The Nagra had not been used since 1995, so I decided I had better get it checked over. Back in the day, the man who had regularly serviced the machine and converted it to timecode was the famous David Lane, who has since passed away (RIP). I knew there was another famous London-based Nagra technician who collects, repairs, and deals in old Nagras, a former Sound Mixer called Mike Harris. One of the issues was finding quarter-inch tape stock, and thankfully Mike had a source in Paris, and ordered some. Mike did a fantastic job servicing it and resetting the tape bias for the new brand of tape we would be using, as the old BASF 468 tape is no longer available. Mike said the machine was in perfect condition and saw no reason why it shouldn’t display the same bulletproof reliability in Norway that Nagras have always been famous for.

In Norway, a significant percentage of the scenes would be filmed on IMAX cameras, and for that reason, I wanted to record on our usual Zaxcom Deva 24, alongside the Nagra. We could supply our usual ISO tracks to Oliver and his Post team, and I completely understood Cary’s wish to have an old school analog feel to the recordings. I also wanted to use two Schoeps Super CMIT booms to give Sound Post the best opportunity to remove the camera noise. Using two Super CMIT’s takes up four tracks, and I also wanted to radio mic every actor, so I knew we would potentially be running up to ten tracks on this part of the film. I recorded my mix onto the Nagra to serve as a reference for Oliver to create a ‘Nagra sound’ from my Deva 24 ISO tracks, it would give him the ability to remix and de-noise individual tracks, rather than being forced into doing a more general de-noise on the Nagra mix track. If I only supplied a mono mix on quarter inch, I worried that it would potentially lead to ADR. As per my usual workflow, it was my aim to supply Sound Post with the most choices possible to have the best ability to get usable production sound.

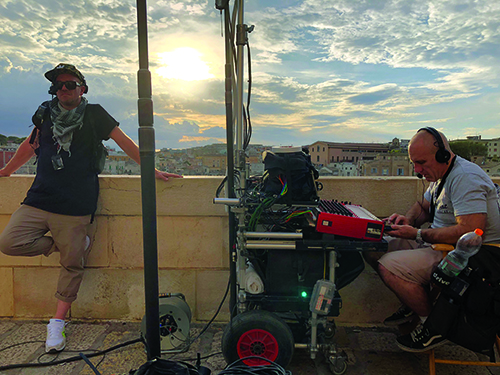

Dylan Jones, Video Playback, Simon on main cart, and Robin on Zuca cart,

Matera

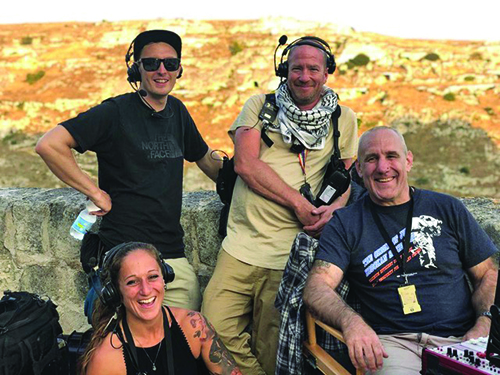

Clockwise from top right: Ben, Arthur, Simon, Frankie

Zuca cart contents

Simon mixing

boat to boat, Italy

It was the end of winter when we arrived in Norway. We were shooting in a forest, waist deep in snow, and on a frozen lake, both of which had their own challenges not least due to the extremely low temperatures we were working in. One of my methods of working in these conditions is to keep the sound cart and all the equipment on it powered up at all times, to avoid heat cycles and frozen switches. The best way to avoid equipment failure, and the way to keep it ready to roll at any time, is to not power cycle it at all. We would leave the equipment in a sound truck all night on location, with the driver instructed to keep the heating in the rear of truck turned on. When we arrived at work each morning, we would power up the warm equipment, and wheel it out into the freezing cold temperatures and leave it switched on all day. This is particularly important for the Nagra as it avoids the brakes from freezing.

It was mainly sound effects we were capturing when we started shooting. It became clear that any ‘camera perspective’ sound would be unusable due to the noise of the IMAX camera, despite the Super CMIT’s, so we concentrated on recording close-up perspectives. The sequence involved one of our lead cast members trudging through the forest in deep snow and arriving at the lake (I don’t want to give away story and plot lines here as you’re potentially reading this article before the movie’s release). I decided that the suspense could be built using the different textures of footsteps through the characters’ journey. We placed three lavs on the actor: one on his left calf, one on his right calf, and one on his chest for his breathing, which was heavy from the effort of walking through the deep snow. When I imagined what I would expect a scene in a Bond movie to sound like, it was these effects with the score that I felt would give Cary the ability to build layers of sound and create suspense in the final mix. The reason we mic’d up the actor’s calf rather than boots is because the snow was so deep that, had we have placed them on the boots, the lavs would have been immersed in snow on every footstep. The actor was wearing ‘crampons’ (metal grips used for walking in snow) that really gave us an ominous sound. Mixed with his deep breathing, I was confident we were getting the exact components Cary would use. To make absolutely sure we had everything covered, and were giving the all-important choices to post, we went off into the forest while the rest of the crew were shooting some high-speed MOS shots. We recorded one of my assistants wearing the same boots and crampons, walking and running at different speeds through different depths of snow, and on ice using the Super CMIT’s; effectively recording a library of on-set Foley for the scene, should Sound Post want to use these additional layers. Snow and ice underfoot are very unique sounds and may be difficult to reproduce on a Foley stage, so I felt it was important to make sure we were completely covered.

One night on the way back from our shooting location to the tech trucks, I was wheeling my cart across the frozen lake. I usually move the cart on my own, as it is a relatively lightweight Eurocart. This leaves my crew to manage the rest of the equipment: follow cart, etc. It was pretty dark and unfortunately, there was a dip in the ice that took me by surprise and one of the cart wheels dropped about twelve inches into a watery hole. This resulted in my losing control of the cart and it going down on its side. All of the equipment was strapped tightly to the cart except the Nagra, which I had not strapped up tightly enough since the last reload. It was on top of the Deva 24, and slipped into the watery hole and was completely submerged for about two seconds until I grabbed it. All of our recordings had also been mirrored on the Deva 24, but I was super concerned I was going to have to tell Cary the next day that the Nagra wasn’t working. The first thing I did was quickly remove the batteries from it to try to avoid shorting it out. We then took the equipment back to the warm sound truck and opened the Nagra up. Luckily, there wasn’t much sign of water ingress and we left the machine open, under an electric fan heater all night on the truck. We told the truck driver how important it was to not unhook from the generator overnight. I feared the worst when we arrived the next morning, we put the batteries in and I held my breath and switched the machine on—it powered up! I played back the previous day’s recordings and they sounded great. We weren’t sending the quarter-inch tapes with dailies to avoid causing issues in Editorial. We would give the whole batch to Sound Post at the end of the job. We took the Nagra to set and recorded on it, and it worked for the rest of the Norway shoot faultlessly. It reminded me why we used the Nagra, and why it stayed on top as the industry’s machine of choice for so many decades.

Part 2 of “Bond 25:” No Time to Die continues in the spring edition as Simon Hayes and crew travel to Jamaica.