I’d like to thank the tens of readers that have responded to my articles for Production Sound & Video. (My friend, Robyn thinks I am eloquent adjacent.) Please know I appreciate hearing from you

by Ric Teller

Today we’re gonna talk about RFs.

First, a disclaimer: My viewpoint on the following subject comes entirely from my personal experiences in entertainment television. I readily admit I am not familiar with the history or the current state of RF’s in what is commonly referred to as single-camera work. Rather than try to fake my way through, I’ll sum up my knowledge. They’re mostly Lectrosonics. You hide ’em.

Sherman set the Wayback Machine for 1981. More than forty years ago, while I was on staff at KTLA, I filled in as the PA mixer on a daytime talk program called Hour Magazine, starring Gary Collins. It was one of my first show calls at KTLA. The audio crew consisted of a mixer, a booth A2 playing music and sweetening with a stack of cart machines, and a PA mixer. At KTLA, boom operators were part of the stage crew, not audio. The Yamaha PM1000 PA board was somewhat familiar. I had seen that console at the iconic Stanal Sound in Kearney (it’s pronounced Car-knee, not Keer-knee), Nebraska. Sitting on top of the mixing board were two Vega RF receivers. The ones that were taller than they were wide, I can’t remember the model number. Neither can Google or Siri, they’re too young. Almost all the audio for the show was done on a Fisher boom except the occasional exercise demonstration segments that required RF lavs. So, we had two RFs but no A2’s. The PA mixer put mics on the host and guest. That was, I believe, the only show I’ve ever done with wireless, but without an A2. In entertainment these days, every game show, talk show, awards show, and contest show employs one or more A2’s to put mics on the talent, contestants, and guests. I believe we set the record at the Academy of Country Music Awards in March.

Someone recently asked me, “What is the origin of the term A2?” How the hell should I know? That term predates the start of my career. I may be old, but I was not the A2 on The Sermon on the Mount … yes, I have worked with him.

KTLA used those Vega RF mics for talk shows, game shows, and the annual Hollywood Christmas Parade where they were handed off to celebrities in cars and on floats on Sunset Boulevard. Other RF mic manufacturers included Nady, Samson, Swintek, and Sony, but in those days, Vega was the nearly unanimous choice for the entertainment.

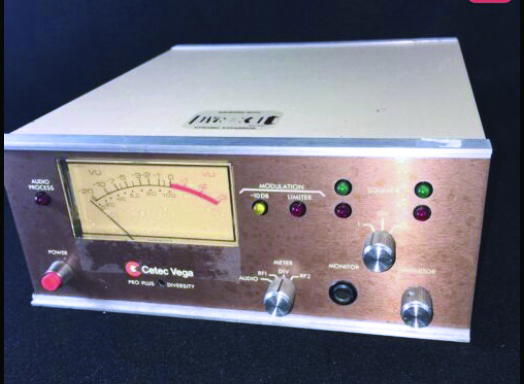

By the time I started freelancing. the more familiar Cetec Vega R42 Wireless Microphone Receiver Pro Plus Diversity Dynex II, better known as “the new Vega,” had become the industry standard for our programs.

They were often delivered in miscellaneous cases and cardboard boxes always requiring the A2’s to create a setup with blocks and boards, not unlike a college dorm bookshelf. These VHF Hi-Band (174 MHz to 216 MHz) units were not frequency agile. Some of you will remember the long antennas on the body packs that were fastened to clothing with a small safety pin or an alligator clip. Although each receiver came with a pair of whip antennas that could be attached to the back panel, the mic package was often accompanied by an additional box filled with antenna splitters and a pile of cables, like a “real find” at a Winegard garage sale. With those parts, we would piece together a useable diversity antenna system that would optimize RF reception.

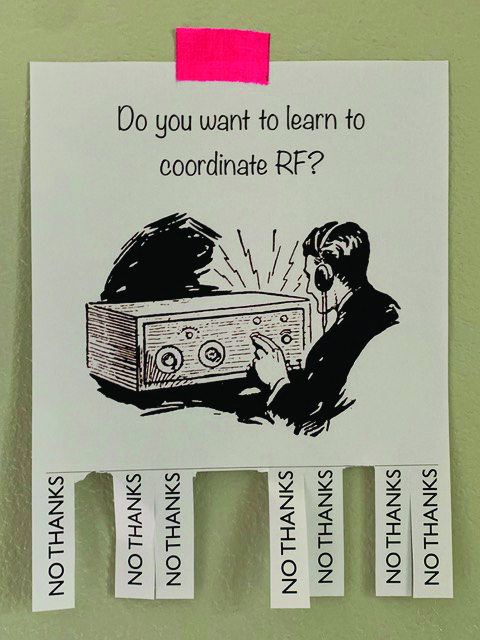

Members of Local 695 and other Audio Engineers throughout the television landscape have many varied jobs. I don’t know how to do most of them. Quite often, overlapping but different skill sets are crucial in the A2 world while working on complicated shows. You may be an accomplished band tech, a trusted lead A2, the patch master, a specialist in hair mics and hidden lavs, or a proficient troubleshooter. You’re probably a combination (my nephew Jonah Horn is a pharmacist and an expert at tossing pizza dough). The fact is that with successes at work, we get hired over and over for the same specific tasks. In time, we achieve a level of efficiency and try to adapt to new technology, but we are not interchangeable in our audio expertise. You can be a Y-7A, a Y-me, or a Y-not, in the end, you know what you know. One of the rarest of these positions is the RF Coordinator. There are so few, they could barely have a minyan to mourn the loss of many frequencies to government auctions. This job is now part of nearly every entertainment special and awards show because producers have decided everything that moves should have an RF mic. And that everything should move.

In 1987, my first Grammy Awards, the show opened with a little RF kerfuffle. The next year, when we returned to the Shrine Auditorium for the 1988 Grammys, we had an RF specialist. When Andy Strauber came on the scene as the first RF coordinator/technician, things were primitive. Most of us couldn’t spell IFR. He owned one. Much of Andy’s job was inventing, improvising, and sometimes willing the equipment to do his bidding. Calculations to avoid intermodulation were made with pencil and paper. I can’t recall how many RFs were in use at that Grammys, probably not that many compared with the shows we do now, but he made them work flawlessly. We hoped this new RF Coordinator position would catch on. Slowly, it became a reality, more and more shows added the position. For the record, twenty years later in 2008, the Academy of Country Music Awards Show held at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, still did not have an RF Coordinator. There were thirty-eight RFs, predominately Shure, a few Sennheiser, and a couple from Audio-Technica, ugh. After many prayers to Our Lady of the Clean Frequency, I’m happy to report all went well. By the way, I recently found out that ugh is not officially part of the Audio-Technica name, maybe just an implied post-nominal.

In the ensuing years, there is no doubt that the position of RF Coordinator has changed drastically. The hardware has become more stable with numerous technical advancements, including the ability to make changes in the transmitter wirelessly. For example, if an unfriendly signal (a bogey) is detected, with the right system you can now change the frequency of one of your transmitters while it is on talent. When possible, RF Coordinators make advance on-site readings with a spectrum analyzer. That and knowing the characteristics of familiar venues is very helpful in pre-planning the allocation of available frequencies. Software such as IAS (Intermodulation Analysis System) by Professional Wireless Systems, and Wireless Workbench from Shure, assist in frequency selection and provide real-time information about RF signal strength, audio level, battery life, and potential interference. The strategy for a big entertainment show often includes the organization of RF mics by function (production, performance, instruments, etc.), a layout for the physical arrangement of the RF rack or racks, and an antenna design which may range from simple to complex, usually a function of the coordinator and vendor.

As the quantity of RFs has gone up (I had two shows last year with nearly seventy, and this year at ACM’s, oh my!), the usable frequency spectrum has diminished. In a series of government auctions, all the 700 MHz and most of the 600 MHz bands have been sold to private companies. With the transition to digital television in 2009, a repack or reassignment of TV channels to fit into the remaining space that has not been auctioned further reduced usable frequencies for RF mics. One bit of favorable technology is that nearly all RF PL’s have disappeared from the RF mic frequency spectrum, most now use the 1.9 DECT systems.

An unexpected change in our use of RFs has come as part of COVID-19 protocols. We no longer use a mic on multiple people without a thorough cleaning. This often requires additional units. In the case of a familiar quiz show, pre-COVID, we would use the same three contestant mics all day moving them from one group of players to the next. Now the A2, Mitch Trueg, mics everyone at the beginning of the day requiring much more hardware. I’ll take a dozen RF lavs for $200.

Near the beginning of this ramble, I reminisced about Hour Magazine and the two Vega RFs. Last September, I worked on The Tony Awards, where we had nearly seventy, and in December, we equaled that amount on The Kennedy Center Honors. The Justino Diaz Tribute at the Kennedy Center featured seven principals and sixteen in the chorus, all singing on hair mics. That was immediately followed by the tribute to Lorne Michaels with another fourteen RFs, almost all lavs. Easily the busiest back-to-back segments in all my years on that show. Or any show.

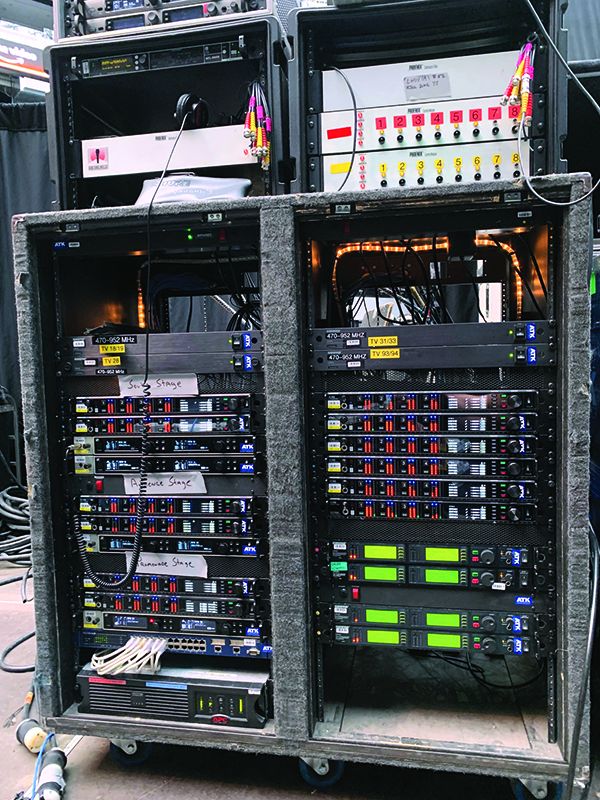

In Las Vegas, for this year’s Academy of Country Music Awards at the new 65,000-seat Allegiant Stadium, RF technicians Stephen Vaughn and Corey Dodd from Soundtronics Wireless began planning several weeks ahead of the early March show date to put together the RF package. About a month out, Corey traveled to the stadium and did a multiple location spectrum analysis inside and outside the venue. Using those readings, a frequency plan was developed. The size of the venue and distances between the four areas assigned for performance and production required two separate filtered antenna systems for the microphones. One was divided into six diversity zones to cover three stages, the other used a Wisycom antenna-over-fiber system to overcome the long runs to the far end of the stadium. Next, hardware was assigned. The show’s thiry-two Shure PSM1000 IEM (in-ear monitor) units were programmed into the quietest available spectrum. The next cleanest frequencies were used for the twenty-four Shure Axient host and production hand mics followed by performance vocal mics, eight Sennheiser 6000’s in the A1-A4 and A5-A8 bands, and thirty Shure Axients in the G57 and X55 ranges. The last bit of the microphone puzzle was the addition of twenty-five Shure UHF-R bodypacks for instruments like acoustic guitars.

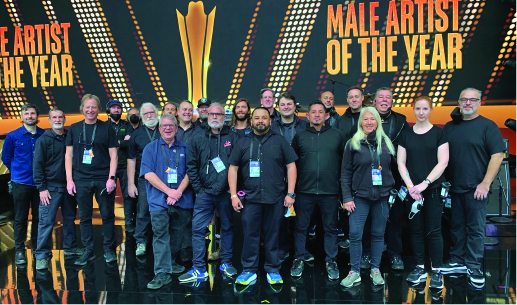

So, let’s review. Stephen and Corey found frequencies for thirty-two IEM’s and eighty-seven microphones. If that wasn’t enough (hint, it was), the comms department added in one hundred twenty-five Bolero wireless RF PL’s made by Reidel all on the 1.9G Hz DECT system. The two-hour live show with twenty-two performances, award presentations, and three hosts spread on stages all over Allegiant Stadium provided the lead A2, Steve Anderson, and his record-setting crew plenty to keep busy.

As my grandma Nellie used to say, “And that’s that.”