by Ric Teller

When I was a kid, I wanted to be an A2.

Said no one. Ever. Perhaps a cowboy, a fireman, or an astronaut. A teacher, a musician, or an athlete. Back then (the 1950s-60s), maybe a small percentage wanted to be a TV cameraman. But an A2? No way. Admittedly, I didn’t know this job existed until 1981 when I started doing shows at KTLA. By then, I was approaching thirty years old. A few years later, when I left the station to begin freelancing, I had gained knowledge. Not exactly expertise but I had some skills. You could say I was making a run at Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule. Now, some 60,385 hours into my post-KTLA career, I am happy to report that I’m still learning. Retention is a bit problematic at times, but I still enjoy the challenges, especially of a big, difficult, live TV show. By the way, if anyone reading this is a Gladwellian scholar, forgive me if I have misused the rule, I have enjoyed some of his books, and many articles in The New Yorker, an esteemed publication where my singular contribution can be found in the Caption Contest number 355.

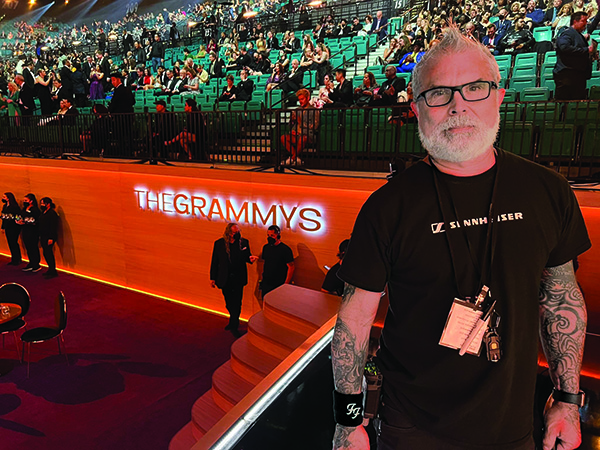

This year, because of some complicated COVID shenanigans, the 64th Annual Grammy Awards show was held in Las Vegas, at the MGM Grand Garden Arena. We traveled to begin the setup just a few hours after wrapping the Oscars. You remember the Oscars, doncha? The MGM has been a familiar location for many award shows, but never the Grammys. There was a bit of a learning curve … ’nuff said.

Personally, I learned a couple of things on the technical side, and one big lesson about show organization. The three-and-a-half-hour live show (it comes with the gift of a three-and-a-half-hour dress rehearsal), consisted of nine awards, a couple of pre-taped segments, and sixteen musical performances divided between the A, B, and Dish (house) stages. The technical lessons were provided by Denali (production truck), Audio Engineer Hugh Healy, and ATK/Claire Global Project Manager/FOH Production Mixer Jeff Peterson. Hugh’s lesson was about a piece of equipment called the Lance Box, used to send audio signals on a single strand of fiber in both directions between the split world near stage and the production truck. It is often used for emergency backup mixes in case a console has issues during a live show. Jeff taught us how to properly set up a DiGiCo rack (the brand of audio console used at FOH and Monitor positions) to send Madi signals to the Pro Tools operators. The Madi streams include all the vocal mics individually, which can be accessed by the Pro Tools operators for tuning purposes. Watching the excellent engineers teach these tasks is educational. Both follow Einstein’s rule: If you can’t explain it to a six year old or an A2, you don’t understand it yourself. For me, retaining the information is a challenge that, on some days, might require a Vulcan mind meld. The organizational lesson I learned was about the importance of paying attention to the entire show, and how one segment affects another. I’d been looking at each performance as an individual entity. That works fine for rehearsal, but on show day, when everyone is dressed in black (a side note, the only other place you might see this many people dressed in black is at an art gallery), the show becomes the sum of its individual parts. I won’t go into the details of what I missed or how it affected the action, but thanks to the stellar work of the A-side and B-side A2’s, all seventy-five inputs for the performance in question were patched, line-checked, and ready to play right on time. Of course, six minutes later, that one was pushed off stage and two other bands arrived. Live TV, gotta love it.

A recent exchange:

Edward Nelson: “Hey Ric, did you know this show is going to be live?”

Ric: “Yes, I know.”

Edward Nelson: “Are you nervous?”

Ric: “Yes, I am.”

Edward Nelson: “Is this your first time?”

Ric: “No, I’ve been nervous before.”

In 2000, the Grammys moved from the Shrine Auditorium to the then-new Staples Center (now Crypto.com Arena) and changed from one performance stage to two. Each Grammys since (except the unusual 2021 version) has featured A and B stages. That first year, Eddie McKarge and I were assigned to the B stage and, with a couple of exceptions, have anchored the B-side ever since.

This year, the A-side led by Damon Andres had the more difficult stage. Of course, they did excellent work.

I do wish I had a better memory of more of the wonderful Grammy performances I’ve seen over the years. If only there was some electronic device to provide a reminder…

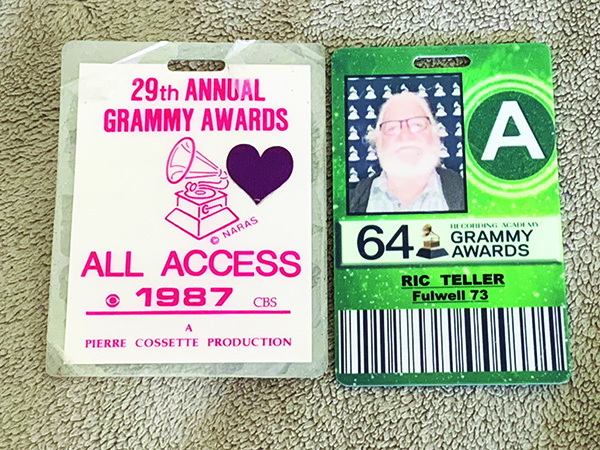

My first was the 29th Grammys in 1987. Paul Simon was one of the performers, I was excited. At that moment, I wanted to be an A2. A couple of years later, Linda Ronstadt performed a song from the beautiful album, Canciones de Mi Padre. In those years, amazing voices like Ronstadt, Whitney Houston, and Luther Vandross were regular contributors. Luciano Pavarotti offered “Nessum dorma,” accompanied by an orchestra in 1999, the last Grammy Awards at the Shrine Auditorium. The 45th Grammys at Madison Square Garden was filled with challenges, not the least of which was to set up the New York Philharmonic across both stages (on the floor, not on risers), in the middle of the show, so they could play some Bernstein, then make them disappear just as quickly. In 2005, Melissa Ethridge, bald from chemotherapy, sang an amazing tribute to Janis Joplin with Joss Stone. Pull this one up on YouTube.

Go ahead. I’ll wait.

2012 brought Paul McCartney performing songs from the Abbey Road medley with guest guitarists Dave Grohl, Bruce Springsteen, and Joe Walsh. The 57th Grammys began with AC/DC. The best opening in my tenure. Just a few years ago, Bonnie Raitt gave us the gift of performing “Angel From Montgomery” for John Prine, who would pass away a few weeks after the ceremony. I am so grateful to have been there for each of these special moments and many more.

The Grammy shows, like all live award and music shows, can be physically tiring. The length of days and the mileage on cement does take a toll. This year, at the MGM Grand Garden Arena, by show day, “my dogs were barking,” an idiomatic phrase attributed to Tad Dorgan, a journalist and cartoonist whose other slang offerings include “dumbbell” (a stupid person); “for crying out loud” (an exclamation of astonishment); “cat’s meow” and “cat’s pajamas” (as superlatives); “applesauce” (nonsense); “cheaters” (eyeglasses); “skimmer” (a hat); “hard-boiled” (tough and unsentimental); “drugstore cowboys” (loafers or ladies’ men); and “as busy as a one-armed paperhanger” (overworked). Personally, to avoid sore feet, I depend on Merino wool socks mostly from Smartwool, and hiking shoes from Oboz or Merrell.

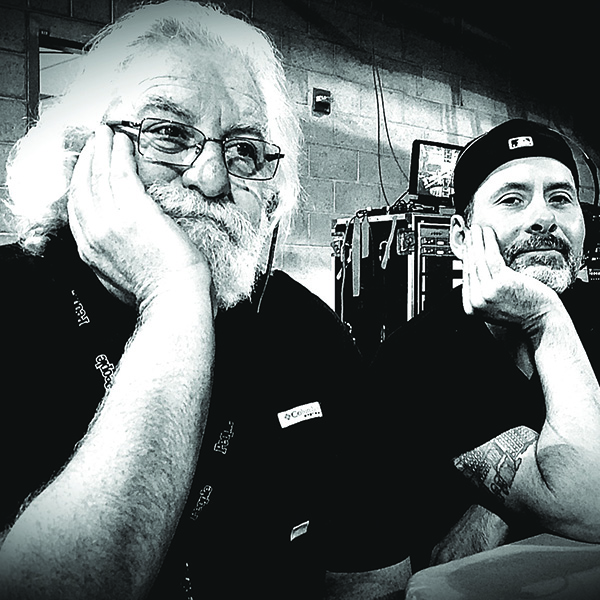

It so happens that I do have a friend who grew up to be a cowboy and another who is a retired fireman. Childhood dreams. I learned early in my career to take the path of most resistance. Anyone can do the easy stuff. Take the hard road. Make a place for yourself in some part of this business that makes you happy. Push through a barrier or two. I was nearly thirty years old when I found out that I wanted to be an A2. By then, astronaut was out of the question. To have been present for the iconic performances listed above has been very special. Standing on the Grammy stage and telling Paul McCartney that to hear him play songs from Abbey Road is one of the pleasures of my life, is certainly a moment I’ll remember forever. But always foremost in my mind are the truly remarkable audio engineers that, for so many years, have made all the long challenging days worthwhile. I’m grateful for each of you and the time we have spent together making a lifetime of memories and lifelong friends.

Near the end of the show, after the last B-side performance had been cleared and the close-down wall was in, I walked out onto the empty B stage realizing that it could be my last time. Got a lump in my throat. It has been a big part of my life. Quite a few years ago, I was in a conversation about how long an A2 should work on the Grammys. The consensus was that age fifty was probably enough. Coming up on twenty years past that, it might be time to pass the torch, it might not, but I don’t regret even one minute.