by Ric Teller

Today the ramble becomes an interview.

In 1979, when I began working at KTLA, twenty-five engineers had worked there for twenty-five years or more, some since the ’40s when television was new in Los Angeles. Working with those experienced pioneers was a terrific beginning. It was interesting and educational. A few years later, I met and worked with Ed Greene, Val Valentin, Doug Nelson, Ron Estes, and other mixers who led the way in entertainment television. At first, I was just trying not to be a spuddler. As time passed, I was fortunate to work with the core group of freelance entertainment A2’s.

So, I’m going to take some questions … from myself. Most of these things are true.

When are you going to retire?

I’m often asked that question. If the phone don’t ring, you’ll know it’s me.

In your career, what has been the most important technology change?

Nearly everything has changed except the XLR (L for latching and R for a version surrounding the female contacts with a synthetic rubber polychloroprene (neoprene) insulation, and the Shure SM 58 which dates back to 1966. When I began, we recorded on tape, and audio connections were made with analog cables. Now it’s nearly all digital. Without a doubt, the one thing that has most directly affected my career is the switch to fiber-optic cable. The old copper 27-pair and 56-pair mult cables were very heavy. I’m glad those long runs between the stage and the production truck are now done with fiber.

What is the most unusual experience you’ve had while putting a lav mic on someone?

In the ’80s, Merv Griffin produced a show called Dance Fever. It was an amateur dance contest with a host, contestants, and celebrity guest judges wearing Vega VHF lavs. One day, I went to mic the three celebs and in the number one position was Zsa Zsa Gabor who told me, “No, dahlink, I don’t wear those.” I offered several possibilities, none were acceptable. She was dressed in a chic outfit with a smart fur-trimmed jacket, mind you, she must have been seventy at the time. I asked if she was going to carry her small, lovely purse onto the set, “Of course, dahlink.” Then I made a most unexpected inquiry, “May I put the transmitter inside your purse and run the microphone wire up the sleeve of your jacket? I’ll hide the mic in a good spot, and no one will be the wiser. “Except you and me, dahlink.” And so, it was. RGR, you would have liked that one.

Do you have a favorite bit of television audio folklore?

If I didn’t, I probably wouldn’t have asked that question. For years, Gene Weed was the director of The Academy of Country Music Awards broadcast. Mark King was, and still is, the A1. Gene liked to give audio notes, even during a live show. He frequently asked for more audience response in the mix. One year, Mark set up a speaker with a volume pot at the director’s position in the truck, giving Gene the ability to raise the level of the audience mics to his taste. It was a success and continued every year thereafter. Of course, he was only controlling that speaker, but I truly believe Gene was convinced for the rest of his life that he was mixing the level of audience response on the broadcast.

Do you have gig envy?

No. I’ve had way more than my share. Unless you count gigs that predated my career. It would have been fun to work on The Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964. That’s about it.

How about a favorite location?

Anywhere I am working with friends. Especially Telluride.

You must have had many opportunities to ask for autographs.

I’ve asked for three. Jerry Lewis signed his book, Dean and Me, while we were at the telethon. Questlove signed Something to Food About at the train station Oscars (I have a small collection of autographed food and cookbooks). The third autograph was collected while we were in Chicago shooting a special at Ravinia Festival, featuring Disney’s Young Musicians Symphony Orchestra. Ernie Banks joined the festivities to conduct “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” I went backstage to put a lav on him. We chatted for a few minutes, then he pulled out a Sharpie and signed my credential.

Do you have a favorite quote?

Two come to mind.

When asked by a frustrated teacher, “Don’t you know anything?”

Yogi Berra answered, “I don’t even suspect anything.”

In the heat of a live TV show. Ed Greene: “I can’t talk, I can’t talk, I can’t even listen.”

Ray Grabner is the sax player in the grey suit. On his left is the noted Colorado photographer, Bernie Gitt.

Name someone who influenced your career.

OK, but I can’t name anyone from television, that list is way too long.

I stood next to Ray Grabner in the Hastings High School Choir. Ray was a senior and anchored the bass section. As a junior, I did my best. Our school put on a musical every other year alternating with a variety show. 1969 was a variety show year. One day, I guess it must have been an early spring day, while we were standing next to each other at the choir rehearsal, Ray asked me if I would like to play in a group that he and Randy Sharp, a tenor, were forming for the show. They already played together in a very popular local band, but this would be a larger group made up of players from a few different bands and at least one with no experience at all. Of course, I said yes and became a member of The Baker’s Dozen. Rehearsals began for the thirteen-piece, brass-heavy band at the Firebird Inn, a second-floor nightclub on Burlington Avenue. Ray sang and played the tenor sax; my instrument was the trombone. We covered The Impressions’ “This Is My Country,” Lou Rawls’ “Dead End Street,” and “Somewhere” from West Side Story, an arrangement that was like the one performed by The Fabulous Flippers, easily the most famous and influential regional horn band in the Midwest. From that beginning, I began to play regularly. A few years later, I joined Ray in the horn section of a popular group called The Elastic Band, hitting the road in a seven-state area. A couple of years after that, I moved to California with another band. By then, the need for trombone players had diminished by two-thirds. Both minor. In 1979, a decade after the Hastings High Variety Show, I began working in television. Ray and I haven’t seen each other for a long time although we still correspond and share a love for bands with horns. There is no doubt in my mind that by inviting me to play in that variety show, Ray opened the door leading to a more than forty-year career.

What is your longest workday (actual time, not the one that felt like it would never end)?

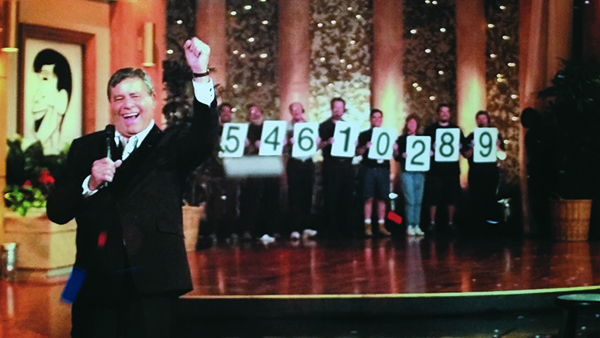

The longest workday I’ve ever had was in Las Vegas at the Jerry Lewis MDA Telethon. I began work at 10 a.m. Sunday with Jerry’s orchestra rehearsal. He sang songs and had great fun with the musicians. The show went on the air at around 6 p.m. on Sunday and ended more than twenty hours later, on Monday afternoon. After the show, we wrapped for about four hours. We worked for thirty-seven hours. After a nap, a bite to eat, and a shower, we drove to an early call at Sony Studios in Culver City and worked the next day. Oh, to be that young again.

A show that lengthy must come with stories.

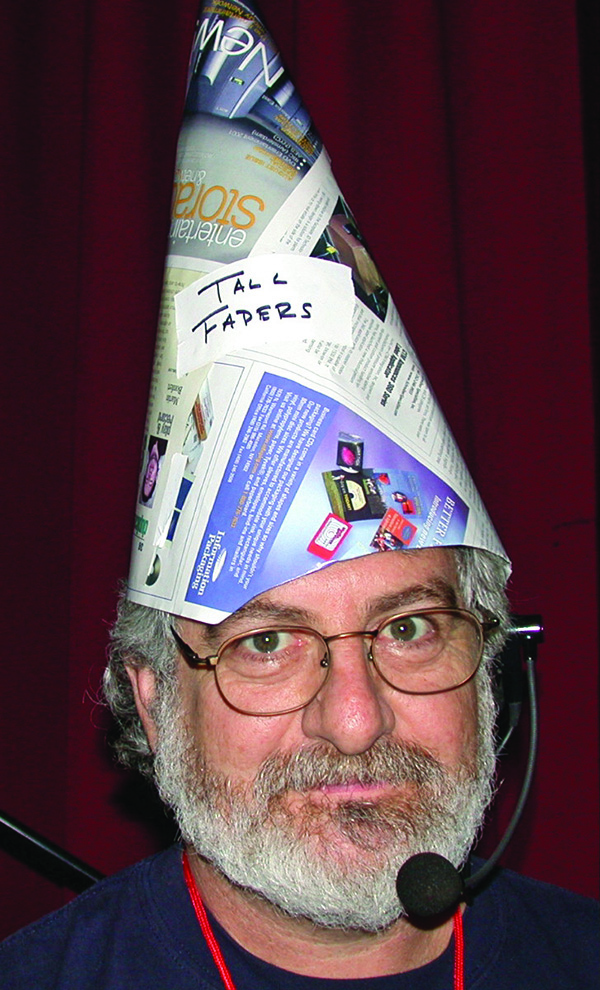

It was exciting to work on something I watched while growing up. In my early years on the show, I worked the overnight shift where we would see the Bubble Guy, the Plate Spinner, Bobby Berosini’s chimps, and the Tall Cedars who inspired an audio group we named the Tall Faders.

I also have fond memories of some of the regular performers like Jack Jones who was so supportive and so talented, and Maureen McGovern who stopped the show one year with her version of “Cloudburst,” backed by the show’s terrific orchestra. Lou Brown was the music director in my first years, Chiz Harris was the drummer, and Don Menza held the tenor sax chair. Toward the end, Lee Muziker wielded the baton, Bernie Dresel played drums and through all the years, the incomparable Rick Baptist anchored the trumpet section. I loved seeing iconic comedians like Don Rickles, Red Buttons (who never got a dinner), Norm Crosby, and Shecky Greene. Henny Youngman performed not long before he died. He was a very old man who needed help getting on stage, then proceeded to machine gun one-liners for about five minutes until we were laughing so hard, we couldn’t catch our breath. In 2000, the electronic tote board failed. We became the human version.

So, you were on television. Was that the only time?

Award shows often use a pop-up mic that can disappear into the stage floor when not in use. One of the many years that the Emmy Awards show took place at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, a newly designed pop-up was installed for the first time. Unlike the common models that are straight and vertically pop up and down, this one had an obtuse angle sort of mimicking a boom arm at the top. One problem. Only the vertical section could disappear leaving the angle exposed above the stage. At some point in the show, Peter Jennings, the personification of news gravitas, was introduced and made an entrance, walking to the pop-up. The operator was a bit late bringing up the mic and Mr. Jennings stepped on the exposed angle, the part where the mic element lived. Flattened the sucker. Done. Kaput. I ran from stage left with an RF hand mic and held it out for Mr. Jennings, thinking he would take it and I could scoot off stage. Nope. He just started talking while I was standing two feet away holding the mic at the proper angle. It was a long speech, it seemed to last forever. In hindsight, I wish the viewers could have seen my thought bubble, channeling Big B. “You’re a grown-ass man, take the damn mic!” When I got home after the show, my phone message machine was blinking. It was my mother, “I saw your hand on TV!”

Have you worked at a live event where something unforgettable happened?

The Jim Valvano speech. We were working the first Espy Awards on March 4, 1993, at The Theater at Madison Square Garden. Coach Valvano had a very aggressive form of cancer. He was slated to receive the inaugural Arthur Ashe Courage and Humanitarian Award. Most thought he would not be able to make the trip to New York from North Carolina, much less give a speech. Many of you know the outcome. He made the trip and gave a speech that no one present will ever forget. He didn’t talk about basketball, he talked about life.

To me, there are three things we all should do every day. We should do this every day of our lives. Number one is laugh. You should laugh every day. Number two is think. You should spend some time in thought. And number three is, you should have your emotions moved to tears, could be happiness or joy. But think about it. If you laugh, you think, and you cry, that’s a full day. That’s a heck of a day.

Near the end, Valvano announced the formation of the V Foundation for Cancer Research, an organization that, to date, has awarded nearly $300 million in grants. Less than two months after the speech, on April 28, Jim Valvano died. As a cancer survivor, I’ll never forget being there and hearing him speak.