Starting From the Top:

Working on Robert Altman’s Nashville

by Fred Schultz, CAS

All photos courtesy of Fred Schultz

Nashville was my very first film job. It came about, like most of my best opportunities, completely by accident. Earlier, I’d moved to Nashville to attend grad school at Vanderbilt, but during the six years required to finish, the market for my degree turned belly-up. Professionally unappreciated, I responded by diving into rock ’n’ roll where, with more enthusiasm than skill, I began mixing rock shows.

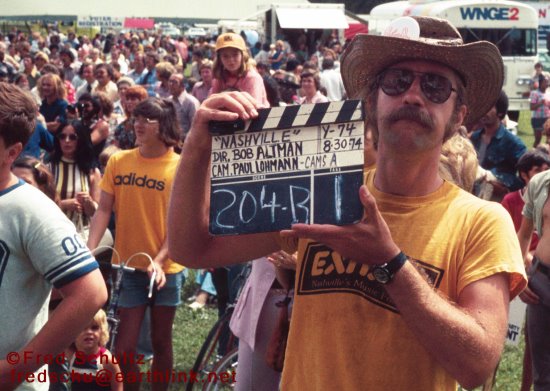

Within the year, I was house mixer at a new music club, run in an uneasy partnership between the regional concert promoter and the young owner of Nashville’s massage parlor chain, a hustler with a love for rock and a cash flow in need of laundering. Before that party crashed, I polished my mixing skills on a stream of incredible talent including Bruce Springsteen (first national tour), KISS (ditto), Iggy Pop, B.B. King, Freddie King, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Seger, and an endless number of their hard-driving southern & midwestern brethren. Opposite page: Fred Schultz with slate. Robert Altman in Centennial Park, Nashville.

So, one year in, the summer of ’74, I was a self-identified rocker, overflowing with ego and lightly warranted self-esteem. That’s when Johnny Rosen, a business-savvy friend and owner of Fanta Sound, phoned me. A movie had come to town and its producers wanted him to find someone to work nights transferring sound for dailies using their pioneering eight-channel tape machine.

So, one year in, the summer of ’74, I was a self-identified rocker, overflowing with ego and lightly warranted self-esteem. That’s when Johnny Rosen, a business-savvy friend and owner of Fanta Sound, phoned me. A movie had come to town and its producers wanted him to find someone to work nights transferring sound for dailies using their pioneering eight-channel tape machine.

That fateful phone call placed me on Robert Altman’s Nashville and in Jim Webb’s sound department. Forty years later, it’s clear I’d been handed a golden opportunity, but at the time it seemed a huge step down. Coming from the egalitarian culture of live music, I was shocked to discover that, as a local hire, I was virtually invisible, working on a crew that for the most part regarded everything about Nashville with abrasive amusement, and which respected film, not music, as the art of highest value.

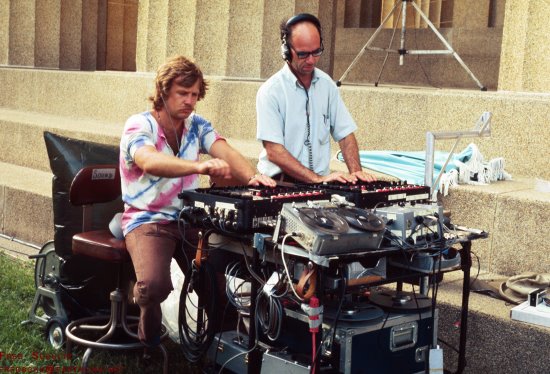

Every day, I reported after wrap to our transfer room in the show’s motel. There, a Teamster delivered the Stevens one-inch 8-track tape machine and production tape rolls straight from Jim’s sound cart, along with his sound log marked up with my instructions.

My job was to transfer three of the eight tracks Jim designated (from wireless, boom, handheld and prerecorded instrumentals) onto sprocketed three-stripe mag stock. A couple of nights later, after the film had been processed and flown back, Jim would do a live mix at a dailies screening for the cast and crew using my three-stripe transfers. Over the years, those screenings have gone on to become the stuff of legend for their high camaraderie, fueled as they were by weed, alcohol and massive talent. However, across the motel courtyard in my transfer room, there was no weed, no alcohol, no camaraderie. Still, the money was good and I’d begun to find the whole film thing fascinating.

The Stevens one-inch 8-track tape recorder was unique in that it operated without a capstan and it ran on car batteries, but was virtually unknown in professional audio circles. Jack Cashin was a USC cinema grad who knew of it and its capabilities, then convinced Altman he ought to use it, then oversaw making it work both technically and in workflow—a trifecta of history-changing contributions for which he’s never been adequately recognized. Altman and Webb first used the Stevens on California Split, then, when planning Nashville, Webb completed the system we know today by bringing in wireless microphones. This full system was used one final time on Buffalo Bill and the Indians, after which thirty years would pass before the film business would again have eight tracks available for their production mixers.

I was able to attend filming at two of their locations. The Exit/In had been my favorite music-listening room since its opening, so when Nashville shot there, I burned my candle on both ends to sit at a table as a background player. This got me close enough to listen while Altman talked his talent through scenes for two days. As far as I knew, all directors did it just like him, right?

I also went to the assassination scene at the Parthenon, and the three photos above are from that day—me playing with the slate, Jim Webb and Chris McLaughlin (Jim’s ace boom operator) behind the sound cart where Chris happily mimed mixing alongside Jim for my photo, and an enthusiastic Altman warming up the crowd as the master of his universe totally oblivious to the pistol clearly visible in his pocket.

But I proved not to be the perfect employee and suffered a fall from grace. One night, a solo vocal track by Karen Black somehow captivated me—it was probably from her SM-58 handheld though I don’t really remember—but I was absolutely convinced that something magic was in that track. And no, drugs were not involved. It was the raw power live music had on me.

I wanted everyone to appreciate exactly that same magic, so, contrary to Jim’s log notes, and ignoring his written instructions as my production mixer—I recorded that one microphone track onto all three strips of the sprocketed mag stock. Inevitably, two nights later at dailies when that particular scene went onscreen, the shit truly hit the fan.

As Karen launched into her song, Jim potted up her instrumentation track only to hear more of the same—her naked a cappella vocal. Apparently, Karen had been insecure about her singing before this, but now with her voice unaccompanied and unsweetened in front of cast and crew, she absolutely freaked. Flipped. Exploded. Jim Webb was on the spot, Robert Altman was on the spot, and a firing of the responsible party was inevitable. I was given the news and sent home. The small upside that night was that no one knew who I was, so no one recognized me on my way out.

An hour or so after I got home, Johnny Rosen phoned. “Think you learned anything here?” he asked. I confessed my naïveté, he got a laugh at me, then reported what had gone down. First, Altman assured Karen Black that he’d had me fired. Then he made it clear that, with the firing done and on record, he didn’t want any delays or compromises going forward with his dailies—nudge, nudge, wink, wink. “Just show up on time tomorrow and do what your mixer tells you,” said Johnny. My lesson learned, I did as instructed and no further word was ever uttered. Fast-forward to last year, nearly four decades later, in a conversation with Jim I finally dared to ask what he remembered about the incident. Always the gentleman, Jim drew a blank on it altogether.

After Nashville wrapped, my career took me back into live music for four more years, including one on the road mixing Johnny Cash, but Hollywood had already set its hook. By 1987, I was living in Los Angeles, a production mixer myself and now brimming with enthusiasm for the MOWs and television episodics that were becoming my bread and butter.

And that’s it. My film career started at the very top, working with Jim Webb on Robert Altman’s Nashville. I was a hands-on user of their paradigm-shifting multi-track production sound recorder. For two months, I was a cog in our industry’s very earliest multitrack film production workflow. Along the way, I screwed up so spectacularly that Altman had me fired. Then had me re-hired.

With the perspective that can come from enough time and distance, I’d like to suggest that sometimes one finds an unsuspected upside to learning your hard lessons while anonymous—wait long enough and some of those lessons may morph into stories worth sharing.

© Fred Schultz 2014