The Distinguished Career of Alan Bernard

by David Waelder

For a remarkable stretch of eight years, from 1987 to 1994, Alan Bernard was nominated for an Emmy every year. He was first nominated in 1977 and received a total of fourteen nominations over the course of his career. On five occasions, he won.

There is no Alan Bernard recorder or mixing panel or microphone boom. His contribution has been the example of practicing his craft at the highest level of skill and grace for fifty years. In the course of that career he encountered, as we all do, some cinematographers who would light him out of a shot or other colleagues who impeded rather than assisted the process. He was always an effective advocate for his department but it’s a testament to both his diplomacy, and the good will he brought to these negotiations, that he maintained personal friendships with all concerned.

Born in Windsor, Ontario, Alan Bernard came from a family originally employed as tailors to the Tsarist Court of Russia. In the turmoil following the Russian Revolution, his grandfather arranged for some members of the family to immigrate to Canada. It was a wise decision; all the family members who remained in Russia perished in one pogrom or another. Although these events preceded his birth and he was never in personal peril, growing up in an environment where one’s safety and welfare can be so arbitrarily disrupted shaped his outlook on life. He was always a person quick to stand up for his crew or anyone else vulnerable to intimidation by more powerful forces.

Alan Bernard’s family moved to the United States while he was still a small child and he attended school here. He became a naturalized citizen and served in the U.S. Army in Korea from 1953 to 1955.

Returning from military service, Alan worked for a while as a Contract Administrator in the Planning Department at Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica. Although it was a responsible position, it didn’t really suit him. When his childhood friend, Dick Overton, arranged an interview for a post-production position in the Sound Department at Fox, Alan jumped at the chance. It was only a six-week job but he ended up staying for six years, starting out loading raw stock in the recorders and gradually working his way up to Recordist and ADR Mixer. Later on he took positions working at MGM and at Warner Brothers.

As a post-production and ADR mixer, Alan worked on many productions, including such notables as “Cleopatra,” “Dr. Zhivago” and “The Godfather.” He remembers David Lean as an especially exacting taskmaster, sometimes working until 3 AM and then bringing the crew back in on forced calls the next morning. Alan was also part of the sound team that received an Oscar for their work on John Frankenheimer’s 1966 film “Grand Prix.” At the time, the Oscar for Sound was awarded to the studios, not the individual mixers. Alan’s son, Scott, remembers being very young and walking down one of the hallways at MGM in Culver City when his dad pointed to a glassed-in display case and said, “See that? That’s my Oscar!”

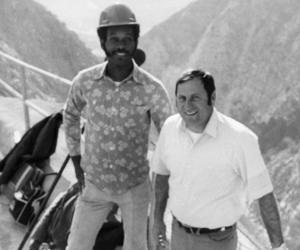

Eventually Alan tired of the routine of work closeted away in dark studios and decided to pursue a career as a Production Sound Mixer. He reasoned that his post-production experience gave him good perspective on what worked for a film and what didn’t. But, with no real production experience it was a long lean year before anyone hired him. His first film as a Production Sound Mixer was “Three the Hard Way” in 1974. Directed by Gordon Parks Jr., son of the director of Shaft, it was a blaxploitation film with good production value. Hal Needham was the stunt coordinator and Lucien Ballard, justifiably famous for “The Wild Bunch” and “True Grit,” was the cinematographer. In short, it was an excellent first project for Alan Bernard, a project where good work could be noticed.

After that film, he was rarely idle. Alan did the final season of the television show “Gunsmoke” with Willie Burton as his boom operator. Willie remembers:

It was a great experience working with Alan Bernard. I was Alan’s Boom Man for approximately two and a half years. I learned so much from him, and not only as a sound person; he taught me a lot about life and family. We were a great team, working very hard and having fun at the same time. After spending so much time working together it was very difficult for me to make the change when I decided to become a production Sound Mixer. I can’t help but think if I hadn’t moved up to mixing, we would probably have worked as a team until he retired. Alan is a great guy and he and his wife treated me like family.

He followed “Gunsmoke” with the “Ghost Busters” TV series and dozens of TV movies.

“A Christmas Story,” the now classic tale of a boy’s yeaning for a Red Ryder BB gun, was his favorite. It’s full of memorable lines. Who can forget Darren McGavin, as Mr. Parker, saying, “He looks like a deranged Easter Bunny.” Or, referring to the prize lamp he has won, “Fra-gee-lay. That must be Italian.” Although filmed largely on location in a cold Ohio winter, we hear every line from Alan Bernard’s tracks; not a single line was looped. (Not that a looped line is a sign of failure; sometimes it’s necessary. But to bring in a whole picture without a looped line is an accomplishment.)

Alan organized a running poker game on almost every project and counted Ernest Borgnine, Ed Asner and the cast of Porky’s among his poker buddies. He was popular with movie stars and crews alike because of the pleasure he took in the company of others. No doubt his success advocating for his crew and department is partly due to this. It’s easier to negotiate when you are a friend first.

Although busy with work for the Studios, Alan managed to find the time to volunteer for service to Local 695. Spanning nearly 30 years, he served the Local in a variety of elected and appointed positions, beginning on the Local 695 Advisory Board (an adjunct to the standing Board) during Thomas Carmen’s administration in the 60’s and then as a Shop Steward, on the Local 695 Executive Board, as a member of the Board of Trustees, and as Secretary-Treasure. Business Representative Jim Osburn says of him, “Anytime you needed a guy on a picket line or to stuff envelopes, Alan would always do it.” He was generous in his support and would help in any way needed.

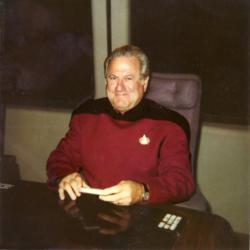

One of Alan Bernard’s Emmy nominations was for 1983’s “The Winds of War.” In 1987 he was offered “War and Remembrance” but declined it to work on “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” He found the long periods away from home demanded by location shooting to be a difficult accommodation for his family and he chose his projects accordingly. It proved to be a fortuitous choice; between 1987 and 2001 he recorded 170 episodes of “The Next Generation” and 98 episodes of its sequel: “Voyager.”

Sometimes it is difficult to make career decisions that give priority to family needs but when we do, the rewards are lasting. Alan has been continuously married to Linda for fifty-six years… no small accomplishment in this very demanding business. Alan’s son, Scott, says his dad never missed any of the important family activities. He was there for all the graduations and birthdays and all the moments that keep a family close. And Scott recalls early morning rides with his mother in the family car to pick up his father from his post-production jobs because Alan often worked night shifts in order to make himself available to his children during the afternoons. He coached Pop Warner football during the years Scott was playing and then stayed on to coach several seasons beyond Scott’s involvement.

It seems that Alan set a good example. Both of his sons, Scott and David, began their careers in the industry at early ages and both are long-time members and contributors to Local 695. Scott continues to follow in his dad’s footsteps, volunteering as a football coach, serving on the Local 695 Board and as past President of the Local and now working in the 695 office as Assistant Representative.

In a business that often demands unreasonable sacrifices of time and energy, Alan has managed to strike a balance between his chosen profession, his family and his community obligations. His best contribution may be the example he shows us by perfecting this balance.