by Tarn Willers AMPS

My first encounter with Jonathan Glazer was a Zoom interview and he was accompanied by his Producer, Jim Wilson, and Sound Designer Johnnie Burn. After initial greetings, Jon cut straight to the chase and explained the concept of the film and that he was going to shoot it with ten cameras, all rolling simultaneously, meaning the whole of every location would be live and potentially in vision. Actors would not be hitting marks and given the freedom to improvise their movements as well, as their dialog and takes would roll for anything up to an hour at a time.

Generally speaking, as a Production Sound Mixer, my role is primarily to capture the dialog and reduce or remove any extraneous sound on set. However, on The Zone of Interest, it felt like my job was almost the opposite, with Jon keen for us to capture every detail no matter how seemingly mundane and the dialog quite often incidental rather than central to the story. What we were asked to do was preserve the sanctity and serenity of a suburban family home. In almost three months working right by the camp at Auschwitz, we never heard any of the horror, not a scream, nor a gunshot. We were making a film about a well-to-do family and their idyllic existence, their garden parties, and social gatherings, their children laughing and playing, picnics with friends, a father paddling his children down the river in their canoe. Whenever I put my headphones on and hit record, I was hearing bedside chit-chat, tea being served, the lights being turned off one by one at bedtime, the sounds of a daily routine in a family home. I certainly wasn’t hearing any of the terror that I knew would underpin the eventual soundtrack to the movie. But this was what I had been asked for and to provide the director with his wish would certainly challenge us in our workflow.

Naturally, the actors would be wearing radio mics wherever possible but the dialog was not always necessarily the most crucial element of a scene. Given his shooting style with multiple hidden cameras (this went way beyond the old two-camera “wide and tight” situation), and his insistence on using authentic sound captured on location, it was immediately clear that we would not be able to have Boom Operators on set and therefore, would need the ability to position microphones to match the sound from the perspective of each camera. In order to do this, we had to design a system whereby we could have multiple microphone positions available to us and the ability to switch microphones around those positions as quickly as possible, according to any changes the director made. Key to this system was that Jon wanted the actors to feel free to interpret their actions and dialog within the environment and that meant no film paraphernalia would be apparent on all sets and locations. Cameras were to be hidden and disguised and the Camera Operators and assistants would work remotely in order that the actors would inhabit their environment with the most freedom possible. Indeed, the set was to be considered live from the moment the actors left the base camp. From this point, no crew were to be present and all equipment was to be concealed and ready to roll as Jon, seeking to capture natural and spontaneous moments, could call action at any time.

The central location for the film was the Hoss family home, a house replicating the actual Hoss family home which stands at the entrance to the Auschwitz camp.

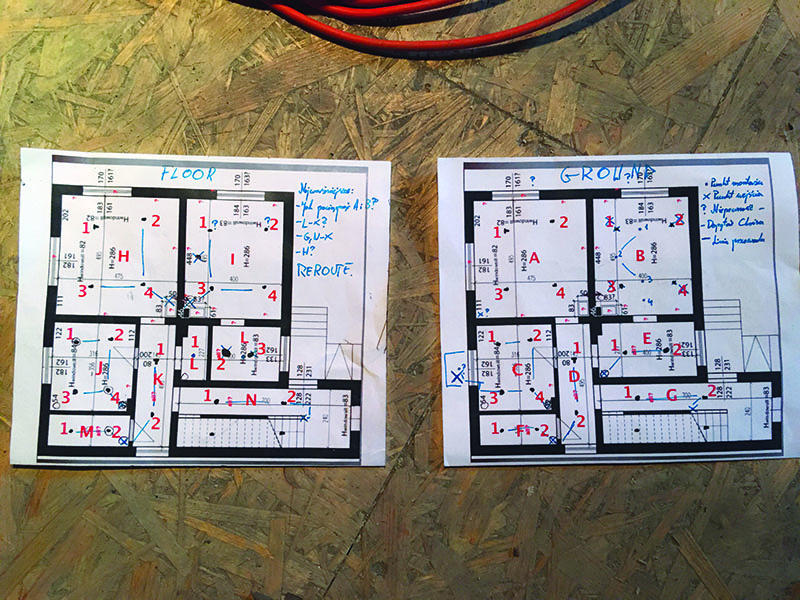

Production Designer Chris Oddy gave us a floor plan of the house and from that we designed a system whereby, bearing in mind that those ten cameras meant there would be no possibility of Boom Operators carrying out their usual roles, we would “mic the house and garden.”

Back in the UK, Johnnie Burn and his team set up a number of tests in order to find the best microphones/techniques to match sound to picture. Ambisonics mics were one idea, and, given their smaller physical footprint, strategically placed radio mics were also considered. However, given the amount of RF on set with the camera department operating remote focus and iris controls on ten cameras which required their own network of Teradek and wi-fi routers stationed around the whole set, various walkie-talkie frequencies coordinated for different departments, etc., I didn’t want to be reliant entirely on RF in a situation which could see us with anything up to twenty mics in play and where the finer details and nuances were so critical to Jon’s idea. With Jon wanting to run long takes, I couldn’t afford to have any interference issues. We decided the best approach would be to (replicate the work of a Boom Operator as closely as possible) and so we decided to suspend cabled mics from the ceilings throughout the house and complement these with plant mics if we could successfully hide them on set. After more discussion with Johnnie, we decided that our approach would be to divide the larger rooms into quarters and cover each quarter with a mic position. Smaller rooms would be halved and corridors would be divided, according to their length. The house was on two floors plus one further room in the attic meaning to cover all those spaces, we had to allocate almost fifty mic positions.

We chose Sennheiser MKH50 and MKH8060 as our go-to mics with the addition of a couple of Schoeps CMIT’s that were made available to us locally. Of course, it would have been ideal to have had a mic for every position to give blanket coverage in the house and garden but given the budget of the movie, there was no way I was getting fifty mics to play with! So, we went with what we had and simply selected the appropriate mic positions, according to the scenes we were shooting on any given day.

The first consideration we encountered was how to get our cables into the house, given that I would be set up, along with the director and video village inside an in-vision container which played as a guard hut on the other side of the camp wall.

And once we had done that, we also had to figure out how we would route cables to all the mic positions we had designated in the house and how my team would be able to quickly choose and move mics between them, according to the requirements of each scene. We decided the easiest way would be for my team to base themselves in the attic and run our network of cables down through the house from there. My team would reposition the mics around the set and connect them into a stage box in the attic which would then feed me down on the ground in the container. In order to get those cables from the attic down to me, Production Designer Chris Oddy provided a period telegraph pole which could remain in vision and a small trench was dug to run cables from the container into and around the garden.

Given that camera and video were also routing their cables through the house, a convenient series of holes had already been pre-drilled which we could use to feed our cables through ceilings and walls.

However, certain rooms did not have the requirement for those larger holes but we still needed to feed those spaces with our cables. In those cases, we drilled holes just large enough to feed our cables and then my 1AS Mateusz Stasiak climbed a ladder and soldered on the XLR connectors in situ.

My team ran our network of cables around the whole house before Chris and his art department, then painted and wallpapered over as many of them as they could and what was left had been OK’d by VFX Supervisor Bodie Clare for paint outs.

And another little trick we devised with our suspended mics was the mounting of metal rings which we found in kits to make dreamcatchers to the ceilings. Using these rings and fishing wire or cable ties, we were then able to position the mics on a 360-degree axis allowing us to more accurately cover the spaces the actors moved in.

In addition to our mainstay MKH50 and 8060’s, we found DPA 4097 micro shotgun mics used with Lectrosonics transmitters an invaluable addition to our armory as these provided us with the ability to hide plant mics to give us specific details and even in the case of the scene where Rudolf and Hedwig lie in their beds talking to one another, capturing the whole dialog. I really can’t speak highly enough of the quality of these mics.

Away from the main house and garden location, we were faced with multiple cameras hidden away on mid and wide lenses observing the action from a distance. The scene with Rudolf taking his kids down the river in their new canoe was shot with cameras in two canoes and several cameras positioned along the riverbank. The actors were again told to work within their environment and improvize dialog and I was told that meant they could get out of the canoe and into the river at any point should they choose to do so. And of course, they did. Obviously this, plus the costumes they wore anyway, meant none of them were on radio mics throughout the scene. We positioned a mic with each camera on the riverbanks to capture perspective and then I rigged DPA 4061’s with Lectrosonics Smb transmitters in the canoe, hiding the transmitters wrapped in cling film and plastic bags (Aquapacs were too bulky to hide) beneath the lip that ran around the canoe and the microphones out on the inside edges of the lip, one either side of the children to cover all the head turns and one on the girl’s seat for the Rudolf dialog. As the weather closed in and we continued filming in the pouring rain, we got the sound, however the water ingress in the canoe eventually cost the lives of three of our brave DPA’s.

One of our first shoot days on the film was the picnic scene which actually features in some of The Zone of Interest publicity shots. Again, the multiple cameras rolled simultaneously and costumes were impractical for radio mics on actors. Again, we hid mics with each camera for perspective and this time, we planted a number of our trusty DPA’s within the picnic paraphernalia to best capture the action and dialog there. As the men in the group then peeled off and went down to and into the water, we relied on our three MKH8060’s hidden just below the bank pointing out at the water.

These were some of the circumstances we encountered in our quest to provide Jonathan Glazer with the most layered and detailed sound recording with which he would create the film we see, and provide Sound Designer Johnnie Burn with just a few colours to add into his palette as he made the film we hear.

Postscript: A year after picture wrap, I received phone call. “Hi Tarn, do you remember the sound of those frogs, birds, and insects at the reeds location? The place that was brimming with natural life? Well, we’d like you to go back and record some of that again for us please.”

And so, I took myself back to said location, a secluded series of lakes in Oswiecim (Auschwitz) southern Poland, just a stone’s throw from the camp and all its dark history, whereupon I had the absolute pleasure of recording the sound of nature without another human presence. A sound so warm and captivating, I felt I could have stayed there for much longer than I did. I’m really pleased and proud that this recording is what the audience hears in the film’s opening sequence, in tandem with Mica Levi’s score, while the audience looks at an entirely black screen.This was the day, without actors and crew, without all the trappings and paraphernalia of filmmaking, that I found myself in The Zone of Interest.