Filming the Perfect COVID-Time Movie

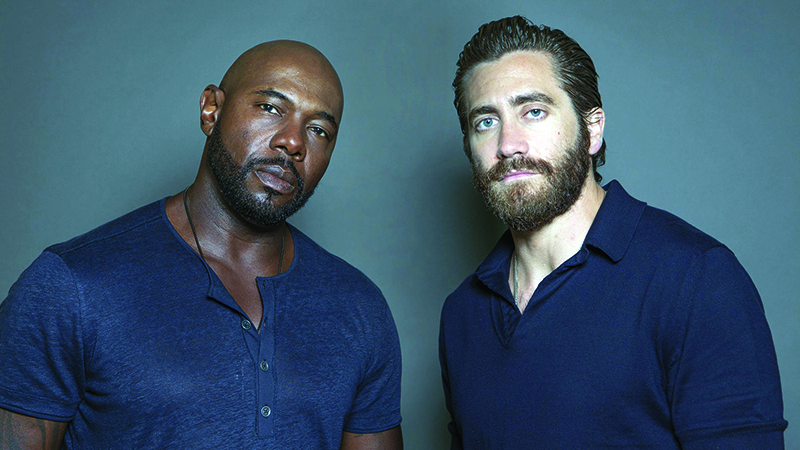

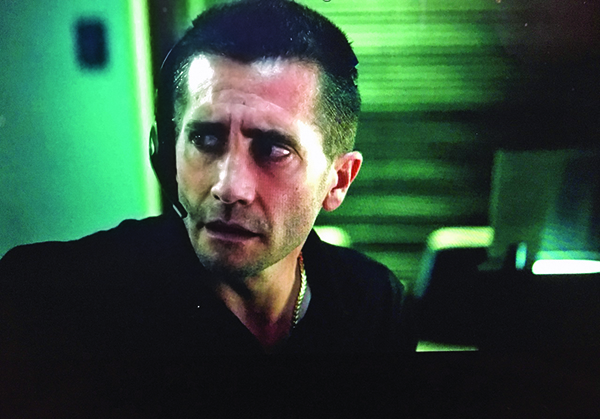

The Guilty is a feature film produced for Netflix based on the 2018 Danish film of the same name (Den Skyldige). Directed by Antoine Fuqua and produced by and starring Jake Gyllenhaal, the story follows a Los Angeles police officer awaiting a hearing for an undisclosed wrong-doing (you find out later) and is assigned to answer emergency calls at the LAPD Communications Division. The film takes place during the evening and night shifts of a single workday.

by Ed Novick

Upon being hired as the Production Sound Mixer, the challenge for me was detailed two months prior to filming: the audience will never see, nor will the filmmakers ever photograph, the 9-1-1 emergency callers that the officer speaks with. Rather, the audience will hear what the officer hears and a good deal of the story will be told by off-camera actors and rich sound design. To make the workflow more complex, our main character will be switching back-and-forth between two communication devices: a cellphone and a Bluetooth headset. I knew I’d have to coordinate with Props and Set Decoration to make sure the devices worn by the officer would be practical and functioning. With that in place, patching the actor’s phone or computer into my mixing panel would be straightforward. Of course, having the off-camera actors in a room close to our set would be a given. How else to ensure quality audio recordings and allow for ease of communication with off-camera talent?

Here’s the problem: It’s 2020 and we live and work in an ongoing COVID-19 environment, so none of the callers will be on stage. In fact, they will all be working from home, wherever that might be. How to proceed?

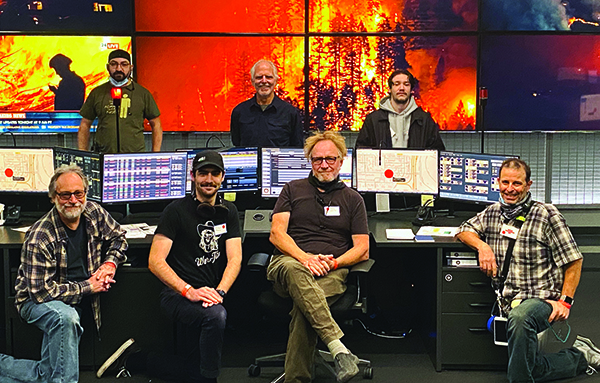

I knew I’d need a reliable system that actors could easily operate without too much audio know-how. I created an “actor’s kit.” Each one was identical and contained a Sound Devices MixPre3, a Shure SM58 microphone, a desk stand, a flexi-arm with a clip, Sony 7506 headphones, and a pair of USB cables (depending on the user’s computer). Factory-sealed, disposable, screw-on mesh windscreens were included with every SM58 to assure COVID safety protocols. SD cards were formatted, folders were created, and the gain was set (based on Zoom rehearsals. I had a rough idea of how loud each character would be). In fact, with 32-bit float recording, I had ample dynamic range available. Instructions were created to help non-audio professionals succeed, including photos and YouTube videos. A spreadsheet was also created to map out which actor had which rig on which day, and were recording to which folder. I intentionally did not include batteries or a power supply for the MixPre3, thereby requiring it to be bus-powered and allowing it serve as both an interface and a recorder. Interface? Yes. All actors would be on a Zoom call (it’s 2020, remember?), as well as myself, the AD’s, and, of course, the lead actor. Off-camera actors were asked to join a separate Zoom call before joining the larger production Zoom. This first Zoom call provided the actors with basic instruction on (1) how to operate the rig; (2) how to assign their audio to the correct folder; (3) how to operate the MixPre3 faders; (4) how to get timecode and jam it into the recorder. Their instructor was Utility Sound Technician Richard Novick, my co-architect on all systems used on the movie.

Oh, yes—timecode. With actors working from home—and home meant Los Angeles, New Orleans, Austin, New York, Toronto, and elsewhere—how to get all recorders in sync with each other, as well as with my on-set recorder and the cameras? My research found three different products that provide satellite-broadcast timecode. After considering price, availability, and ease of operation, we selected the Betso system. A Betso GPS calibration module, connected to a Betso SBOX-1N sync box, would be able to output timecode on Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) to the recorders used by the actors, as well as to me on set. We contacted Betso, learned they had eleven units left in stock, and production purchased all of them. This meant that we could provide timecode to ten actors’ kits, and to me, and everything would be in sync.

Rehearsals commenced in the week prior to production start, but with actors at home. Jake Gyllenhaal was given a duplicate Bluetooth headset to practice with, as adjusting the attached boom mic was important to his action. Zoom worked well enough to get everyone connected, at least for these rehearsals.

Admittedly, Day One of shooting was buggy. The issues we encountered were too many Zoom users, not enough bandwidth, as well as a lag that proved to be inconsistent, causing a varying offset between “real time” and “phone call time.” I pivoted quickly for Day Two (and beyond) to a cellular-based system, where everyone phoned into a conference call and remained muted until their turn. I had two cellphones in the conference, one for output (I captured the aggregate phone call on an isolated track) and one for input so I could provide sound effects and vocal cues to the actors in the conference. JK Audio’s Bluekeeper provided the interface between cellphones and the mixing panel, and the application Soundplant was employed for triggering audio cues.

Multiple audio sends had to be used as well. For example, the lighting dimmer board operator, who needed to coordinate the illuminated call signal at Jake’s desk with the calls occurring in the story, wore a Lectrosonics M4R receiver with pre-fade boom mic in his left ear, post-fade phone call track in his right ear, and channel one of the walkie-talkie in both, all routed through my Sonosax mixer.

As much as possible, the filmmakers wanted to film the drama like a play. That is, let it run as long as the narrative (or the camera card) would allow. With takes that often exceeded twenty-five minutes, the strain on Knox White, my Boom Operator and frequent collaborator for twenty-five years, would be substantial. Production agreed to rent an exoskeleton system for Knox to wear that would help alleviate the physical strain on his body from holding the boom for such long periods of time. Fellow Boom Operator and Local 695 member Bryan Cahill was able to set us up with a rig and instruction.

Knox was able to monitor his boom mic in pre-fade listen, while Comtek and the dailies mix were fed the scratch phone call, allowing both sides of the call to be heard. Granted, the phone call and the picture were out of sync, but that’s a matter easily fixed in Editorial. I monitored the phone call, Knox’s boom, the actor lavs, and my laptop, busily switching solo between them. When production was completed, I was able to retrieve the actor-recorded audio from all ten actors’ kits and at last, provide clean isolated tracks to post production.

In all, this little COVID-friendly movie, simple on the face of it (one main actor, mostly seated, in just two rooms), had a great many moving parts and proved to be among the most challenging projects I’ve worked on. But since the craft was able to assist the star rather than hinder him in order to best tell the story, then I’ll say all the extra effort was well worth it.

Special thanks to:

Peter Schneider and all the helpful folks at Gotham Sound for their support. Patrick Martens and Stephen Vittoria, whose command of language is enviable.