The Evolution in Motion Capture on THE JUNGLE BOOK and Beyond

by Richard Lightstone CAS AMPS

In 1937, Walt Disney began experimenting with methods to realistically portray characters in the movie Snow White. They adopted a technique called rotoscoping, invented earlier by Max Fleischer, where individual frames of movie film were traced onto animation cells as a means of speeding up the animation process.

Leaping forward four decades with the advance of computer processing, 3D animation was used in the motion picture Futureworld (1976). As technology and computer speeds improved, new techniques were sought to capture human motion. A more sophisticated, computer-based motion tracking technology was needed, and a number of technologies were developed to address these developing human images.

What Is Motion Capture, written by Scott Dyer, Jeff Martin and John Zulauf in 1995, defines the process as “measuring an object’s position and orientation in physical space, then recording that information in a computer-usable form. Objects of interest include human and nonhuman bodies, facial expressions, camera or light positions, and other elements in a scene.”

The majority of motion capture is done by our Video Engineers of Local 695 and requires high technical skills at problem solving often in the form of writing new software.

Glenn Derry and Dan Moore are perhaps the busiest and most experienced in the field of motion capture with credits such as Avatar, Tin-Tin and The Aviator. I spoke with Dan at their new seven-thousand-square-foot facility in Van Nuys and Glenn and Dan a week later via a phone conference in Vancouver and Atlanta respectively. Their most recent screen credits include the sophisticated and elegant imagery seen in Disney’s The Jungle Book.

Glenn Derry describes the unique challenges of their work on The Jungle Book. “We’ve got the character Mowgli, played by Neel Sethi, and he’s the only live-action element in the entire picture. All of the work in terms of shot design has happened months before in a completely virtualized environment with the Director of Photography, Bill Pope, holding the camera and creating the shots, and working with the CD (Computer Design) team to come up with the look. We were lighting our physical elements to match the CD in contrast to the traditional shooting of live action driving the computer graphics.” Dan continues, “We designed a way to track the camera in real time so that we could overlay their hyper photo realistic virtual scenes, shot months before and mix it with the live action as we were shooting in real time.”

They shot on multiple stages requiring video feeds in every location, interfacing all the tracking cameras, deliverables and dailies for editorial. Dan and Gary Martinez managed a large server with the master footage while designing solutions for Director Jon Favreau. Derry, Moore and Martinez came up with an elegant solution to project shadows in real time on Neel, who was walking on a forty-foot turntable.

“We were always developing software,” Derry continues. “On The Jungle Book in particular, we wrote a few different applications including a delivery tool that enabled them to view all of the material. One piece of software that we at Technoprops wrote for the show dealt with color reconstruction of the camera raw images.” ‘Debayering,’ a common term used for this process, was named after Dr. Bryce Bayer at Eastman Kodak. “Once the software was written, we titled our process the ‘De Bear Necessities,’ and delivered this to editorial and production. Normally a convoluted, complicated and expensive process now was estimated to save production between one and two hundred thousand dollars.”

Previously, the director and producers would need dailies starting from a specific beginning and going to an end point, which was complicated, time-consuming, and expensive to load and combine with essential data. Because of the need to generate the visual effects in the deliverables, they wrote new code that any editor could use to drag an EDL (edit decision list) into a folder and automatically generate exactly what visual effects were needed in their deliverables.

Using a system from the company Natural Point, and their OptiTrack cameras, they built a half-dozen moveable twentyfive- foot towers containing six motion capture cameras each. Glenn explains, “The system that we built integrated the OptiTrack motion capture system with our own camera hardware and software, this was high-end inertial measurement unit data that was on the cameras. We created a hybridized optical inertial tracking system allowing them to choose how much of this was coming from the inertial center versus the optical motion capture system.

“Further, in-house, we developed infrared active markers that allowed production to work in an environment where you could do real set lighting and still be captured by the motion capture (Mo-cap) cameras; a big breakthrough in our industry. If we could register the live-action camera from at least three of the six movable towers, then the live movable object (prop and or actor) within the volume and the virtual Jungle Bookworld would be aligned or calibrated.”

“On the performance side,” adds Derry, “what we’re really doing is capturing the actors and trying to record the essence of what they do and combine that with the ‘jungle’ world as quickly and efficiently as possible. We need to visualize the image for the director and the DP.”

Moore adds, “How do we figure out how to have a virtual bear (Baloo) walking next to the actor within the confines of a stage, so it looks like they’re walking through the woods? These were one of many challenges that would come up frequently during the course of production. We also needed to have the virtual and live-action elements combined and represented on the monitors, which were placed around the set. Glenn Derry came up with the solution for the ‘Baloo and Mowgli’ challenge and decided on a turntable, with the ability to articulate the movement along with his motion control base to make it all come together.” “We worked with Legacy Effects, who make really well articulated animatronics,” explains Robbie Derry. “Their job was to make Baloo, a bear, so they manufactured a shell that rides on a motion control base. Neel would sit on it as if he was riding Baloo. The motion base has a 360-degree rotational top as well as a 30-degree tilt, pan and roll.” They could import the final animation data into the onset computers and drive the camera and the motion base simultaneously to get the true movement of what Neel should be doing in the scene. Robbie Derry continues, “When we played back the animation on top of the real-world scenario, through camera, you could see Neel riding on it, with the full background, the bear was moving, the bear was turning, and we were capturing all this in real time, which was a really cool thing to be able to do. It allowed the director to be able to line up shots correctly; and move the camera on the fly. We could track where that camera was in 3D space, on the stage, at any time, and then back feed the animation cycles through the lens. So, when you’re looking through the camera, you could see the bear. I could walk around with the camera and see the bear from all sides. This is something you couldn’t do prior to being able to track camera data like this.” The heart of Technoprops and Video Hawks operation is at a facility in Van Nuys. Its two floors are crowded with equipment. Dan is very proud of the machine shop managed by Kim Derry, his son, Robbie. Angelica Luna, Gary Martinez, Mike Davis and others are also an integral part of their companies. The shop contains three Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines where they can fabricate whatever they might need for a project, from custom head rigs to the carts and the frames that hold components. Dan explained, “Having the metal shop here, and the talent just allows you to respond very quickly to what’s needed, rather than having to sub all this work out.”

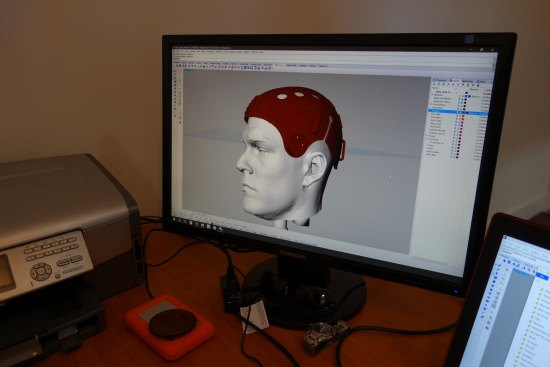

One of the many creative technologies available in their facility is a Vacuform machine that makes precision molds of actors’ faces, enabling the green registration marks to be placed in exactly the same place day after day. The green tracking markers are used by the Computer Graphics house to track the movement of the facial muscles.

They also manufacture the active markers with surface mount LEDs that can glow green or emit an infrared signal that can be used in exterior light. Computer gaming and motion capture films often use actors in black suits who wear reflective markers over their body. This allows a computer to see the movement of the actors and later reconstruct the movement with the character from the story (i.e., Neytiri from Avatar). This often would take place in an indoor environment with even overall lighting. With Active Markers, virtual actors can interact with live actors, in an outdoor or indoor environment, and use traditional set lighting.

Robbie Derry does the 3D CAD design and the 3D printing of the custom-fitted head rigs with a single arm holding the 2K high-resolution cameras that are capable of shooting at 120FPS for facial capture. Each actor wears a small custommade computer serving as a video capture recorder. They can tap into these recorders wirelessly, on their own Wi-Fi network using Ubiquity routers built into Pelican cases. With their Web application, they can use a cellphone, iPad, or any device to watch the video back and also function as a confidence monitor.

Before the technological advances developed by the motion capture industry, the old paradigm of Mo-cap involved an animator sitting at a computer with the director, or the DP, having to decide what live-camera shots were needed, and what set construction was required. Now we are capable of putting new tools in the hands of directors and directors of photography, enabling them to create scenes from their imaginations in real time instead of waiting for the animators and the computer modelers to generate their environments.

Glenn Derry sums it up, “The end result is the creation of a virtual reality, where the director can interact with all the actors and elements in real time. Teamwork is key because there’s so much integration between pre-visualization, live action and post production. Ninety percent of our entertainment will be generated in virtual reality in the near future. We are doing the groundwork for what will be the norm in ten years.”

“Walt Disney would be impressed with today’s technology,” says Moore. “On Jungle Book, Technoprops and Video Hawks served a creative team of filmmakers and a director’s imagination. Virtual reality technology will have an impact on our entire industry and the members at Local 695.”