by James Delhauer

The digital revolution has certainly lived up to its name over the last few years. It’s odd to think that most of us working in film and television today still remember a time when the very concept of a digital workflow was a pipe dream; something that aspiring artists did to learn the craft. The first entirely digital film, Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, was released more than twenty years ago using the earliest high-definition processes. The files recorded on that film (a term that doesn’t even technically apply) were revolutionary for the time but progress marches ever forward. Today, hardware capable of producing higher quality, images are available at your local Best Buy, and professional sets utilize devices capable of recording uncompressed 4K, 8K, and now even 12K images. All of that data needs to be processed. This year’s new MacBook Pro’s might be the tool that Local 695 technicians need to do it.

Whether you love or hate the Apple ecosystem of products, there is no denying that they’ve garnered respect in creative industries and have become one of the leading industry standards for artists around the world. Last year, Apple surprised the world when it announced that it would be abandoning its 15-year relationship with Intel and would begin producing its own line of processors for all products across the Mac line of personal computers. The new M1 processor debuted in the fall of 2020 in the 13-inch MacBook laptops and Mac Mini desktop, boasting impressive specifications at an even more impressive price point. Months later, a line of all-in-one iMac’s with identical specs was added to the M1 family. This first-generation M1 processor yielded promising results but its hardware specifications were well below what many considered necessary for a “professional” workstation. This caused users to turn toward the future, wondering when Apple would unveil new processors for its Pro series of products. After months of speculation and delays, attributed to the ongoing global chip shortage, the company announced its new 14-inch and 16-inch MacBook Pro’s, powered by M1 Pro and M1 Max processors.

The units offer a substantial jump in performance compared to the initial M1 lineup from last year, boasting 10-core central processing units (CPU’s) and 16-core Neural Engines with up to 32-core graphics processing units (GPU’s). One of the biggest critiques of the original M1 series was that Apple’s MacBooks, Mac Mini’s, and iMac models were all restricted to just 16gb of unified memory, a configuration in which memory is shared between the CPU and GPU rather than each unit having its own dedicated pool of RAM. The new units have raised this cap to 64gb, removing one of the largest performance bottlenecks facing power users. Apple has also introduced a brand-new Media Engine into their laptops, a hardware accelerated feature used to decode or encode ProRes, h.264, and HEVC codec video files. This frees up resources for the rest of the machine, significantly increasing productivity when working with these types of files. These improvements make the M1 Pro and Max laptops ideal for high-resolution transcodes, 3D rendering, and high track count audio work. In fact, Apple has gone so far as to boast that at max specifications, their $3,899 16-inch M1 Max units offer better 8K ProRes performance than the 28-core CPU version of their 2019 Mac Pro desktop, which retails for a minimum of $12,999 and up to $54,199 when fully upgraded.

Many users will also be delighted to learn that Apple has restored some of the previously discontinued input ports. The new MacBook Pro’s come equipped with three Thunderbolt 4 ports, an HDMI port for an external monitor, an SDXC card reader, and a dedicated charging port compatible with Apple MagSafe 3 chargers. This removes some of the need for expensive dongles and adapters that many have criticized since the 2016 refresh of the Apple notebook line. However, the company remains adamantly opposed to supporting aging interfaces like USB 3.0, CAT 5 Ethernet, and their own Thunderbolt 2 ports, meaning users will still require adapter docks for fairly standard external devices like hard drives, non-Apple brand external mouses & keyboards, and any type of networking equipment.

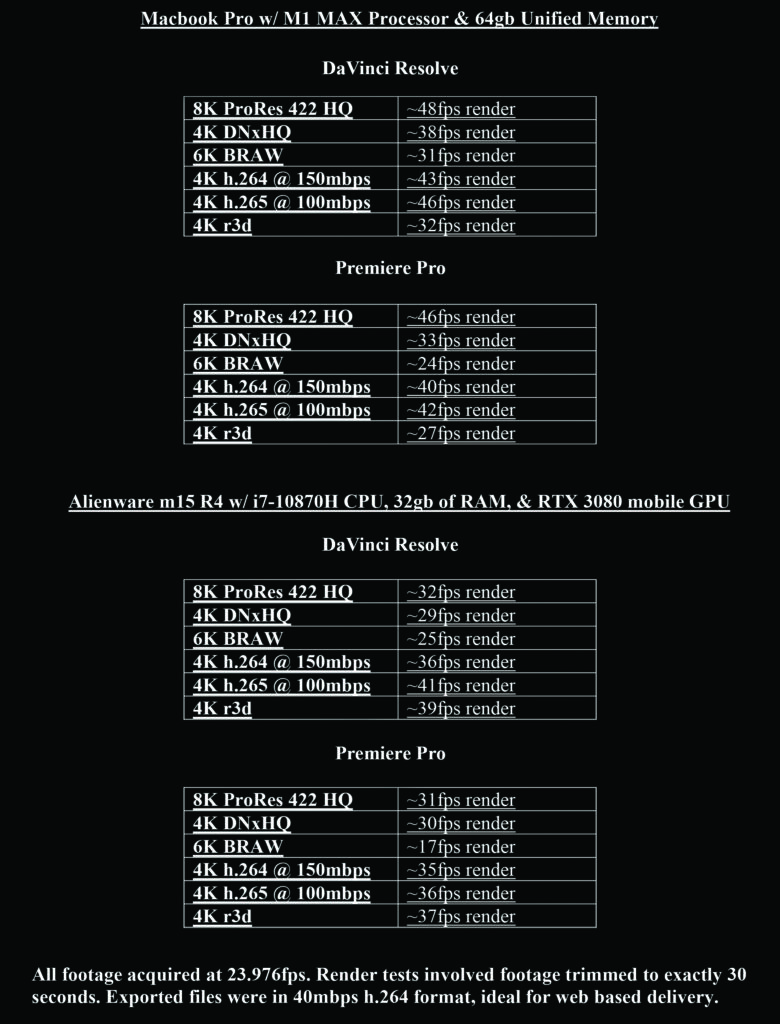

But bold claims from a trillion-dollar company can’t compare to hands-on experience, so I got my hands on a 16-inch MacBook Pro with an M1 Max processor and 64gb of RAM and put it head-to-head against my 2021 Alienware m15 R4 gaming laptop, which runs on an i7-10870H CPU, RTX 3080 GPU, 32gb of RAM, and Windows 10 Pro. The results were interesting to say the least.

For my tests, I downloaded or acquired samples of a variety of different file formats, including 8K ProRes 422 HQ, 4K DNxHQ, 6K BRAW, 4K h.264, 4K h.265, and 4K r3d files. All files were exported in UHD ProRes 422 HQ and h.264 at 40mbps, as these are the most commonly accepted industry delivery formats for broadcast and web content. All content was captured at 23.976 and was processed both in Adobe Premiere Pro and DaVinci Resolve.

The accompanying chart can be used for a full overview of the results but the upshot is that Apple has put a real contender on the market, which dominates the Alienware’s scores across the board, with an overwhelming advantage when it comes to ProRes content. Premiere Pro, long known for issues in terms of stability, crashed far less frequently on the Apple computer compared to the Windows one. DaVinci Resolve, though reasonably stable on both operating systems, seems to process content more efficiently in macOS. The Alienware struggled with 8K content across the board, quickly flagging VRAM errors if a sequence grew longer than a couple of minutes. The same error appeared when adding an included LUT and seven adjustment nodes to ProRes and h.264 footage. It only took four adjustment notes to generate these errors when working with DNxHQ or h.264 footage. Meanwhile, the M1 Max laptop kept chugging along, only throwing up a VRAM error when I hunted down a piece of 29.97 12K BRAW footage and added seventeen adjustment notes just for the purposes of trying to break the system. Interestingly, however, the Alienware did have a slight edge when it came to processing 4K r3d files captured on a camera from Red. This would seem to corroborate other online reports that Apple’s new flagship notebook struggles with Red video, suggesting that some further optimization is required. Whether this optimization will ultimately come from Red or Apple (if at all) remains to be seen.

My biggest question leading up to release was the issue of thermal throttling, a safety feature included in most modern systems to prevent overheating. If the processor reaches a certain temperature, the system reduces the amount of supplied power. While this protects the computer from melting its own hardware, it comes with a noticeable reduction in performance. This issue has made its way into the mainstream in recent years, as developers have struggled to pack as much power into the smallest possible gizmos and gadgets, with Apple having particular difficulty circumventing the issue. In 2019, MacBook Pro’s equipped with more expensive i9 processors had such a problem with thermal throttling that they often performed worse than units outfitted with cheaper i7 processors. The original M1 MacBook’s suffered from throttling issues as well, leading many to question whether it was possible to put that level of performance power into a 13-inch laptop.

While I cannot comment on the 14-inch model, the 16-inch M1 Max seems to have very few issues in terms of throttling. To test the issue, I transcoded thirty seconds of 8K ProRes 422 HQ to DNxHQ, which completed in twenty-seven seconds. I then created a two-hour timeline and filled it with files of various lengths, framerates, codecs, and resolutions—just to make the processor as angry as possible. After completing that render three hours later, I reran the original thirty second ProRes to DNxHQ test, which completed in twenty-nine seconds. A longer series of tests would be necessary to determine for sure but this would suggest that the issue of thermal throttling has been reduced, if not eliminated. This can likely be attributed to the low draw power of the unit, with high intensity tasks only drawing about forty watts for sustained usage. This trumps my Alienware, which achieves less impressive results on a 110-watt draw. In this instance, Apple really is able to do more with less, making the M1 Pro and Max MacBook’s two of the eco-friendlier workstations on the market.

Performance notwithstanding, the computer does feature some nice quality-of-life improvements. The divisive touch bar, first introduced in the 2016 edition of the MacBook Pro, has been removed, and the fragile tap pad keyboard interface has been replaced with a more traditional mechanical button setup. Typing on this computer feels nicer and, speaking as someone with joint problems in my hands, the softer impact when typing is much appreciated. The display is lovely and displays rich, contrasted colors that seem consistent with the iPhone XR and iPhone 13 Pro with which I was able to compare it. Out of a sense of nostalgic curiosity, I watched the aforementioned Attack of the Clones on this overpowered display, and while that film definitely shows its age, it looks and sounds spectacular on the MacBook Pro. The image is crisp, clear, and sharp and, more impressively for a laptop, the same can be said of the sound. It’s amazing how far we have come in just twenty years of digital filmmaking.

The M1 Pro retails starting at $1,999 for the 14-inch model and $2,499 for the 16-inch model, while the M1 Max will set you back $2,399 and $3,499 in those sizes respectively.