by Mac Ruth

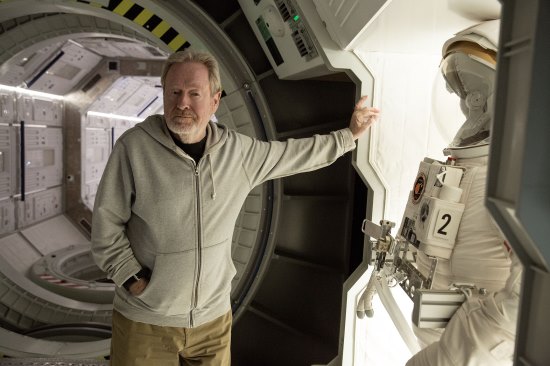

The Martian was one of the highest grossing movies of 2015 and a critical success. Helmed by legendary director Sir Ridley Scott, starring Matt Damon and a significant ensemble cast, the film realistically created the Mars landscape, outer space and earth. Sir Ridley tasked us with creating a reality on the set and thus convincing the audience of the plausible reality of near future Mars travel.

The Mars Rover vehicle, the spacesuits, the communication systems, sets, props and the performances all had to work to further this goal. From my fi rst discussions with the production team, I knew that this show would be extremely challenging.

As Production Sound Mixers, I strongly believe we are collaborators in the process and there to help facilitate the director’s vision in capturing the best audio performance, however, there is so much more to this.

Capturing that audio is the culmination of a long sequence of events that we work toward, starting in prep. This is where some of our most valuable but most underappreciated work is conducted. Most importantly, we get to ride with the creative vision of the film. Our colleague, Mark Ulano CAS AMPS, in the context of another film, wonderfully discusses this. We have so much to learn from his attention to detail at this stage of the game.

During prep, we get to the “nuts and bolts” with other departments, discussing all the aspects of our interactions so they go smoothly on the shooting day. Right away we knew that we would be dealing with spacesuits so that became mission number one. Simon Hayes set the bar very high on Prometheus, when he worked for Mr. Scott. Oscar-winning Costume Designer Janty Yates, who also worked on Prometheus, was extremely helpful in allowing us early access with the spacesuit design team. She solicited our input on the “look” as we were lobbying for a helmet mic that would be effective in the acoustic space, while also looking realistic. We proposed a “miniboom microphone ” which would be visible, as we believed that the NASA helmet engineers would come to the same conclusion.

The concept was approved by Ms.Yates and Ridley Scott and our team custom manufactured the mini-booms using the DPA 4061 as our preferred microphone after more than a week of testing. There was also a second hidden DPA in the lower part of the helmet, which was added as backup. If the primary helmet mic failed, the actor in the suit would not be able to communicate with anyone on the set or be recorded. This two-mic setup in the helmets was what Simon Hayes and his crew established on Prometheus. I have immense respect for Simon and his team’s work, their experience and his efforts to further our craft.

We worked closely in prep and throughout the shoot with the spacesuit team, who were all wonderful, led by Michael Mooney, who has worked closely with Ms. Yates and Mr. Scott many times. They found ways to solidly build the radio mic transmitters and IEM receivers into the spacesuits, yet be easily accessible.

The spacesuits were hot and claustrophobic and it was not easy for the costumers to keep the actors comfortable, as they wanted to rip the helmets off as soon as a scene was finished. We had jumpers built in all the connectors, so everything could be disconnected quickly. The spacesuit team strove to find the quietest solutions for cooling and ventilation. This helped enormously in our ability to record usable performances with the spacesuits.

We used Lectrosonics SMV and SMQV transmitters in the spacesuits and dual Venue rack receivers on both the sound cart and the communication systems rig, eliminating the need for cables between the two setups.

For the IEM system, we used four units of the Shure PSM900 transmitters with antenna combiners allowing for eight individual in-ear mixes, with the Shure P9RA receiver units built into the spacesuits. Due to the dimension of the spacesuits, the Shure IEM receivers had to be placed in close proximity to the two high-power Lectrosonics transmitters. They all worked perfectly with no interference. We chose the Shure SE215 earphones for the talent with individual silicone ear tips.

György Mohai, our talented Communications System Engineer, was tasked with quickly setting up individual mixes for the actors, Ridley Scott, our assistant directors and key members of the stunt team. György used a Roland M-200i, which has a nice compact form and can be DC powered for the individual in-ear mixes. He also used the iPad interface to operate while on set and utilized the Roland’s onboard dynamics processors and EQ to effectively filter and compress the dialog to cut through the noise of the Mars storm sequence. Shot with six Ritter fans, at the Korda Studios, blasting a specially fabricated “Mars surface mixture,” creating a blackout storm that made communication between everyone on the set practically impossible, except for the actors performing in the scene and those needing to communicate with them in real-time. A huge win.

A significant challenge was the “live communications” between NASA and JPL while strategizing the Mars rescue efforts. The scenes were shot simultaneously, on separate sets, so the actors could perform with each other in real time. There were many “Skype” communications that occurred in the film and one of the difficulties in making this happen was the manpower as the sets were distant from one another, requiring multiple boom operators. The audio also had to be fed to the actors; we used ear wigs or speakers when an ear wig was visible in the shot.

I am a big proponent of cabled booms and cabled communication systems when required, as the distance between the sets would have made wireless communications next to impossible. These sets proved challenging and required more manpower including the Video Assist Department, who had to deliver the desired “split-screen” video and audio to the Director. Calculating the audio delays needed throughout the signal chain to Ridley, while watching three or more 3D and 2D camera rigs, required constant attention, depending on what combination of equipment we were using on the different sets.

There were many practical video monitors requiring sound even when the actors were only reacting to our created cable news footage. The practical video monitor team, coordinated by Mark Jordan’s Compuhire, were great collaborators. The favored setup involved taking a video feed from the Compuhire crew and my department controlling the audio playback on set over a combination of either speakers, in-ear monitors or through the practical video monitors themselves.

Unique in my experience was the need for triggered playback of off-camera lines, also requiring additional manpower. The production began with shooting the NASA Mission Control set first. Mission Control would be communicating with the astronauts throughout several sequences including the rescue. We had not shot the scenes with the astronauts so their recorded dialog wasn’t available. Instead, we prerecorded and mixed temp-dialog with our dedicated Pro Tools Playback Operator, and the talented Second Unit Production Sound Mixer, György Rajna. His recordings were used for playback for the Mission Control technicians to react to. The playback dialog had to be triggered live to the needs of the on-set talent. Additionally, Ridley would ask for some “squelch” to make the playback dialog more realistic. György quickly added a side-chain of white noise dead air, “radio comms” EQ filtering and compression, adding the sense of reality that Mr. Scott was seeking.

As filming progressed, the production dialog replaced the temp recordings that we used as off-camera playback for the actors in the scenes. Later, we added Tamás Székely, the award-winning Berlinale Film Festival local Re-recording Mixer, for the Pro Tools dialog playback.

When I say triggered, I mean dedicated capable personnel, working in timed conjunction with the actors. As well as continually building and editing a playback session as the film progressed and replacing the temp with the production audio in the film. It was a superior challenge making this available to the actors throughout production.

The communication and playback system challenges didn’t end there. We had to create live on-set sound effects that we played back to help motivate performance. During the MAV and ARES launch sequences, the actors needed to react to the power of the liftoff. This was no ordinary sequence, as the cockpit sets were designed to violently shake while the cameras were on separate rigs that could move smoothly. We played our rocket launch sound effects at an extremely loud level, both amplified on-set and in-ear, inside the spacesuits to complement the violent shaking motion and to motivate the actors as well as the entire crew.

My recording setup was capable of a high track count to accommodate the double mic’ing strategy, as well as the playback and communication system signals. I chose to use two linked Sound Devices 788Ts which gave me the proven field reliability I’m used to and allowing for the 788Ts variable output delay feature for the communication systems, Video Assist monitors and performance cues around camera.

With the multiple-camera angles and the simultaneous shooting on two or more sets, we used both boom microphones and wireless in every shot. However, the majority of the “money close-ups” were recorded with a Schoeps CMC6MK41 or CCM41 rig on Ambient and Panamic booms.

Timecode was generated with an Ambient Recording ACC- 501 Clockit controller on the mix cart and the camera slates and Denecke SB-Ts on the 3ality Stereo camera rigs, all playing very nicely together.

Wadi Rum, Jordan, was our location for the surface of Mars where Matt Damon drove a working Rover over great distances. Our wireless microphones and communication systems were put to the greatest test here. This is an aspect of our workflow that couldn’t be tested in prep so we were rightfully concerned.

We set up our recording and communication relay system in a flatbed Toyota Hilux pickup truck. The frequency spectrum was incredibly clean, however, the distances between us, the Rover and Ridley were great and pushed the technical limits of reception.

Matt Damon was free-driving the vehicle and luckily, we managed to keep to about a kilometer. We were constantly faced with super-wide shots to highlight the vast landscapes and there was nowhere to hide, so we were forced to find distances between the two on the fly. Happily, our communication systems worked amazingly well under the duress of this environment. We were certainly pushed to the limits at times, but all in all, we were able to satisfy the technical and creative needs of the film under these most demanding circumstances. This location was the most convincing confirmation of our efforts on The Martian.

It was an incredible feeling to complete the movie to Mr. Scott’s and the cast’s satisfaction. We felt like the Sound Department contributed to the “reality” that Ridley Scott had asked for.

I have to thank my crew, Sam Stella as First Assistant Sound and primary Boom Operator; Bal Varga as Primary Wireless Engineer and fabricator of the custom spacesuit rigs; György Mihályi as Boom Operator and the longest working member of my team. György Mohai as Communications Systems Specialist and Tamás Székely as Playback Specialist; György Rajna as Second Unit Production Sound Mixer and influential workflow engineer, Áron Havasi, Bence Németh and Attila Kohári as additional manpower.

I would be remiss in not thanking the work of our Post Sound team who collaborated with me from start to finish. Oliver Tarney, Supervising Sound Editor who provided great support, along with Paul Massey and Mark Taylor, the Re-recording Mixers. Rachael Tate, our Dialog Editor and self-proclaimed iZotope RX ninja, was a huge ally in preserving the original dialog recordings.

I believe the Sound Department’s efforts are tangibly felt in the finished product of The Martian, not only transparently as it should be in the recording of the performances, but in so many more ways as well.