by Simon Hayes AMPS CAS

Filmmaking has changed, and sound crews have had to adapt to new methods of working. Over the last fifteen years, one of the biggest changes we have seen is the introduction of multiple cameras on all projects.

Multi-cameras used to be the domain of high-budget feature films, sitcoms, and soap operas. Production sound crews are finding multiple cameras being used on all formats and budgets, due to the lower cost of shooting digitally. This has resulted in a change to how we capture production sound, and requiring a completely different approach.

Two Booms

There was a time that once or twice a day, the Utility Sound Technician would swing the second boom in a wide shot to capture a line of dialog that boom one was finding it difficult to cover. Or on an over-the-shoulder of the actor whose back is to camera, mouth slightly revealed, and is likely to ad-lib or overlap the onscreen dialog. Running a second boom full time is now the only way of supplying the Dialog Editors with complete coverage on a show shooting two cameras or more.

When the Director is shooting two cameras, we are going to come up against the ‘wide and tight’ scenario that makes getting high-quality boom dialog so difficult. It doesn’t matter how many times the Director and DP promise they will use matching headroom on both cameras and not run wide and tight, it will happen regularly. The last thing a Director wants to hear is a Production Sound Mixer continually asking them to re-adjust the shot or shoot separately, even though the Sound Mixer is trying to save the original performances.

Running a pair of booms means that the two Boom Ops can commit their mics to fewer cast members, allowing each to play the scene significantly closer to the frame line of the wide shot. Let’s say the scene has four cast and the two Boom Operators split the coverage. They can take greater risks swinging closer to the edge of the wide frame, allowing the Sound Mixer to reduce the gain which not only reduces background noise, but also room reflections, and helps to create a closer perspective that is more likely to match the closer shot.

Two booms can help when working with Directors who use multiple cameras to shoot longer sequences. Ridley Scott is well known for using three cameras, and positioning them around a set so his cast can play a whole scene and capture the coverage from three angles in a single take. The best way to cope with this shooting style is to assign a specific boom to a camera, so that it always has a microphone covering what the lens is shooting.

The two Boom Operators will use a combination of these two workflows on a shot-to-shot basis, even changing from scenario one to scenario two within the same take. The two booms provide flexibility and the best chance for the Production Sound Mixer to deliver great tracks adequately covering what the cameras shoot.

When negotiating for two Boom Operators, I try to describe this to Producers, informing them I will be able to deliver twice as much usable production dialog, and ask them if they can afford not to have two Boom Operators? More and more shows have two Boom Operators in their credits which is really encouraging, especially on episodic television whose per-episode budgets are rising, and expecting feature-film levels of creative quality from every department.

Wireless Microphones

We used to watch the way a scene was blocked and make a decision whether radio mics would be necessary. We simply cannot make an accurate judgment despite watching a scene being blocked of when the second camera is going to shoot coverage during a wide shot where we cannot get a boom close enough. This is why many of us now choose to wire the cast as a matter of course, so that when we are presented with an impossible scenario for the booms, we are ready. Even though we dislike having to radio all the cast all day, there are benefits. We don’t have to slow the shoot down and ask to mic the cast after the cameras set up angles the booms cannot cover. It also means less negotiation with on-set costumes when from the get-go, everyone knows the actors will be lav’d at all times. The question now becomes ‘how’ rather than ‘why’?

Delivering lav tracks gives the Picture and Dialog Editors choices that will really help in post production. However, radio mic’ing the cast for every scene creates a much higher workload for the sound team, along with running a second boom full time. This can easily turn into an impossible task for the Utility Sound Technician if they are being expected to boom all day, and also put lavs on the entire cast.

This is why the modern sound crew is more often a four-person team of the Production Sound Mixer, two Boom Operators, and a Utility Sound Technician (UST). This splits the workload and allows the UST to work closely with the cast and the Costume Department on the wiring, as well as carefully watching monitors during shooting to check if any lavs are being exposed.

Frequency Coordination

Gone are the days when all departments could rock up onto a job and simply expect their radio equipment to work. The Sound Department is using many more radio frequencies, including wireless booms, as well as radio mic’ing everyone. Frequency use on films sets used to only be necessary for a couple of departments, however, we are coping with the Camera Department using remote focus, iris control, and remote heads. The Video Department is transmitting and receiving their images via Teradek, the Grips are using crane comms, the Lighting Department using Wi-Fi to remote control their lamps, and Special Effects Department walkie-talkies. Even before the Sound Department encounters bandwidth issues on the locations we are shooting in, the film crew has an enormous amount of wireless, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi equipment trying to be shoehorned on the set.

The Sound Department is the only department that really understands the subtleties and technical challenges of wireless frequency co-ordination. Unmanaged frequency plots will result in each department attempting to solve their numerous interference issues by increasing output power on their devices, mistakenly thinking that will cure the problems without realising they are causing inter-mods (interleaving modulations) across other department’s equipment.

The way we approach this during prep is asking Production to contact each HOD, and have a person in their department to collaborate with the rest of the departments regarding radio frequencies. We send an Excel spreadsheet to each department and ask their allocated person to input all of the equipment frequencies they are intending to use to the spread sheet. This is quite an eye opener with some departments completely unaware of the frequencies their gear works in. The spreadsheet motivates departments who are inexperienced in radio equipment to, at the very least, get up to speed on the frequencies they require. We then work out which departments are potentially going to have conflicting frequencies with other departments. Then ascertain who is on fixed, and who is on variable frequencies, and ask those using equipment on variable frequencies to compromise by moving into some free space to help the departments on fixed frequencies.

A common issue caused by Teradeks is not setting a locked fixed frequency, so it will channel hop whenever they experience a weak signal, causing big issues for all the other equipment in the same bands (often the other equipment the Camera Department is using…). We are finding that the most congested bands are the Wi-Fi frequencies of 2.4ghz and 5ghz, and when the transmit power gets ramped up, they begin to conflict with our radio mics, not to mention control commands with Zaxnet.

I delegate the entire frequency issue to my Utility Technician. However, the job is certainly gaining an increasingly heavier workload, and the ability to swing a boom, lav the actors, and deal with frequency issues is now a much larger task.

VOG

An outgrowth of the COVID-19 protocols is the Sound Department’s responsibilities of a permanent ‘Voice of God’ (VOG). This used to be something we’d only encounter on large sets which required the 1st AD’s voice to be amplified louder than the output of a loud haler. We are increasingly working with Directors who like to use a VOG at all times. Once the Director is using a VOG, then the 1st AD is going to need one too, so now we are suddenly wrangling handheld mics, receivers, and a large 5kw PA which has to be moved from scene to scene and from set to set. The VOG requirement seems to have grown as a direct result of shooting digitally which has also led to a ‘tent culture’ where Directors and DP’s spend far more time in ‘Ezee Up’ tents, off the set so they can view large LED monitors in darker conditions that are more favourable for judging the DP’s lighting set up.

Comteks

There was a time when the amount of Comteks we were required to provide on an average-size film or TV show was ten to fifteen sets. It is not uncommon now for me and my team to be expected to provide forty Comteks on a show. This has increased the amount of battery changes we have to do on a daily basis, and the number of receivers we are trying to find at the end of each day. The way my team manages this new phenomenon is treating Comteks the same way as the AD’s handle walkie-talkies. We assign a crew member their own unit with their name printed on it using a label maker, and ask them to sign for it. We maintain a record of each crew member’s Comtek serial number, so if the unit is lost, we know who lost it, and add it to the L&D report. Each department is responsible for charging their own rechargeable batteries. Some departments are reluctant to take responsibility for a Comtek full time, exclaiming that they only need one once in a while. However, it’s guaranteed a Grip or an AD will approach the Mixer or Utility Sound at the last moment needing to hear the dialog for a cue, and we will hear “waiting for sound” from the 1st AD as the Utility scrambles.

Visual Effects

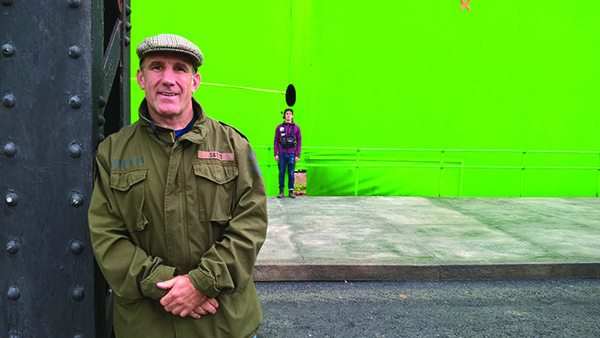

We are now in an era of advanced VFX technology which has benefitted Boom Operators in getting their microphones closer over the actors. There are different scenarios, from complete blue screen and green screen work which allows our boom mics to be in shot all the time to the more popular, real set pieces in foreground with the deep backgrounds being green screen or blue screen. The challenge for our Boom Operators is the booms cannot cross behind the foreground sets, or the actor, unless the boom poles are green or blue, otherwise they will be needed to be painted out, which is costly.

Popularised by Director David Fincher, known unofficially as the ‘House of Cards’ method, is the booms are allowed to cross into locked-off wide shots to capture dialog, matching the tighter lenses of the other cameras. As long as the wide shot delivers a ‘plate’ free of booms, the VFX Departments can remove them in post production. The Boom Operators wait a couple of seconds after the clapper board has left frame before swinging into position and ‘busting’ the frame, which gives each take its own unique couple of seconds of ‘plate’ (particularly important if there is changing light through a window, etc.).

The ability to remove booms from moving shots is also getting more inexpensive each year. Some Directors recognise that VFX boom removal and ADR both have a financial cost, but ADR has a potential performance penalty. VFX removal protects the cast’s original performances. Depending on the Director, DP, VFX Supervisor and budget, the Sound Mixer and Boom Operators must skilfully navigate the discussion. We can either ‘make or break’ boom removal depending on our technical knowledge of what is possible to be achieved, and our ability to articulate it eloquently.

Computing Skills

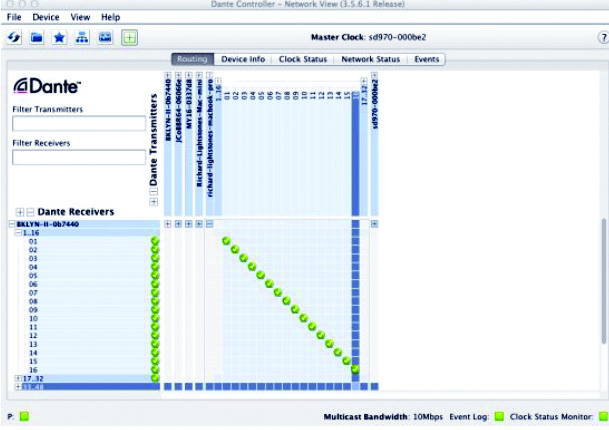

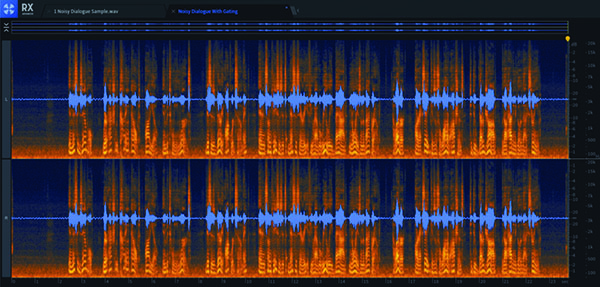

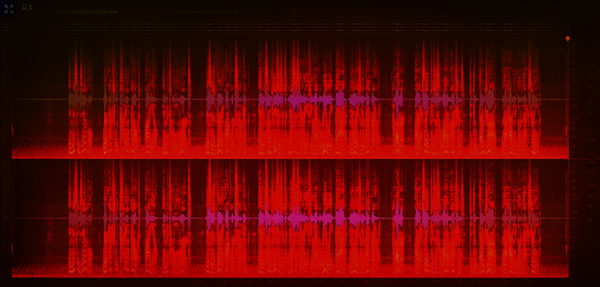

We are expected to be well versed in the world of computers not only to keep our equipment up to date, including recorders, radio mics, and timecode, but also to have the ability to use ancillary equipment such as Pro Tools, iZotope, Cedar DNS, Dante, and many other plugins. We have to interface with our sound equipment: from firmware updates, knowledge of hard drives, CF cards, Micro SD cards, formats, and workflows. It really pays to have at least one member of the sound team who is an expert in both PC and MAC as we encounter dozens of issues over the course of a show that requires an in-depth knowledge of both operating systems. It would literally be impossible to run a modern sound team without having instant access to that expertise at all times as we problem solve and interface with computer equipment to creatively perform our jobs.

Conclusion

Modern Sound Departments need to have old school skills that previous generations of sound teams had in abundance, but also the ability to keep adding to our knowledge and remain current. Equipment is literally changing show-to-show in our department and all the other departments collectively. Without collaboration, our ability to provide creative solutions for Directors and cast are limited. The more knowledge we have, not just in our own domain but of other departments, allows us a greater advantage to provide brilliant sound recordings, and the all-important performances we have been hired to support and protect.