The Sound of Birdman

or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

By Thomas Varga

It was a great honor to receive the CAS Award for Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Birdman. Being nominated by my peers for a BAFTA Award, an Oscar and then receiving the CAS Award, makes the latter so valuable to me.

I had been approached by many talented mixers who asked me the same question: “How did you do it?” Well, hopefully, I will shed some light on the process.

Initially, I was asked by a line producer I had worked with on Everybody’s Fine and the Washington, DC, portion of Breach. She informed me about the project and set up an interview at Kaufman Astoria Studios, where the sets for Birdman were being built. I was familiar with Alejandro Iñárritu’s work and thought the script was brilliant. I was looking forward to meeting him and working on the project.

The interview turned out to be one of the most surreal I’ve ever experienced. I entered a room with Alejandro, expecting it to be one-on-one. I was surprised to see several producers, the Production Designer, Kevin Thompson, and the Cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki “Chivo.”

They were all in the room to collectively drive home the point that Birdman was going to be “impossible” to record. “I don’t know how you’re going to do it” was expressed to me many times. Chivo made a point of saying that he didn’t think it would be feasible to use a boom because of the complexity of the shots. They were clearly concerned about the technical aspects of tackling such a nonconventional movie, and what that would mean for the soundtrack.

Luckily for me, one of our Producers, John Lesher, called James Gray, the Director of The Immigrant, a project in which we collaborated on a year prior. James said good things about me so I basically just told Alejandro that “whatever you guys throw at me, I can handle. I am not afraid.” I also made it clear that I loved the project, was willing to accept the challenge and would be honored to be a part of their team.

Within fifteen minutes of leaving the studio, I received a call from the Line Producer, while on the subway home.“They loved you. We’d like to offer you the job.” I didn’t expect the decision so quickly. Taking a moment to reflect on what just happened, the last scene of The Graduate came to mind. Dustin Hoffman is on the bus after stealing Elaine away from her wedding. It was a “be careful what you ask for, because you just might get it” moment.

I met with my crew, Adam Sanchez and Brendan O’Brien, and it was apparent that in order to handle the challenges of this film, I would need to upgrade my wireless and bag rig. I decided on a wideband Lectrosonics VR Field unit with four different blocks, to go along with my SMs, SMVs and SMQVs. I have always believed that in New York City, the more blocks the merrier.

[The three of us figuring it all out: Tom Varga and Boom Operators Brendan O’Brien and Adam Sanchez work out the next scene. (Photo: Alison Cohen Rosa)]

In my experience, the SMQVs can be too large to hide in tricky situations, although they are bombproof. I usually put the smaller SMs on women or use them with tight-fitting clothing on men. My bag rig included a Sound Devices 788 with a CL- 8. I also invested in several Lectrosonics 401 and 411 receivers to match the cart-based Venue Field receivers. With this setup, if I couldn’t work off the cart, I could grab the bag, go portable and not have to touch the transmitters on the actors. I could also record part of a scene outside on the cart and have the interior portion covered with a portable rig simultaneously. Luckily, I never had to do this on Birdman.

I have an assortment of COS-11s and B-6s. My main cart now houses two 788s and a Cooper CS-106 with a seventh channel. The Main mix is on Channel 1, Iso’s are 2 through 8. On Birdman, I used one 788 as my main recorder and a Fostex 824 as a backup. Yes, I know, the 824 is currently in a giant pile of unused 824s on the “Island of Misfit Toys.” I used Schoeps MK-41s for all interior dialog and 416s and 816s for all the exteriors. The Schoeps CMIT 5U was too long to use with the very low ceilings that were purposely designed to make the audience feel more “claustrophobic.”

Effects gathering was one of the most fun parts of the job. A good friend and very talented sound mixer, Mark Cochi, lent to me a Holophone H2 7.1 surround Dummy head, for gathering Times Square sound effects. The locations department found us a couple of offices that were directly above Times Square. This allowed me to record many different interior perspectives with large crowds below. I recorded passes with the windows closed, partly open, fully opened and at different distances to the window; close, two feet back, four feet back, etc. Locations also found a theater in Times Square that would allow me to record the crowds entering before a Broadway play. Martin Hernandez and Aaron Glascock, our wonderful Supervising Sound Editors, were happy with all the ambiences I was able to record. Finding the time to break away from the set to record useful ambience is often a challenge. Luckily, Alejandro was very adamant that the AD department budget time for us to gather these unique sounds.

I had set aside a good three weeks of prep time to incorporate all the new gear. However, on a Friday, almost a month before production, with piles of various cables and connectors lying on the floor, I received a phone call. “The director and producers would like you to be part of the rehearsal process.” I thought “Wow, what a great idea.” Then the bomb was dropped. “We want you to start this Monday, recording all of the rehearsals to the Alexa with the stand-ins running the lines.”

I had a stress-induced out-of-body experience and all I could hear was “Come Sail Away” by Styx. I spent the next forty-eight hours straight building a better bag rig, accommodating seven receivers and a wireless boom option. I also had to make an Alexa input cable and a Comtek feed from the bag. I I have almost exclusively worked off a cart, so putting this entire rig together in a weekend was a daunting task. After a soldering marathon and a groggy Monday morning, I had everything up and running and along with the rest of the crew, learned just how tricky these shots were going to be.

I carried the bag behind the camera, exposed the lavs on the stand-ins and tried to figure out at what point in the shots we could utilize booms. I later found out that they had rehearsed in LA and used on-camera microphones which sounded awful. I was brought in to help Alejandro hear the stand-ins so he could gauge the timing of the dialog with the camera moves. This proved to be an invaluable experience in planning an approach to getting booms over the actors instead of relying on wires.

To me, it is a testament to Alejandro’s vision to see how little the camera blocking changed from the initial rehearsals. We ended up bringing first team in to rehearse for a week before principal photography. This gave us yet another opportunity at squeezing in booms whenever possible. When we started principal photography, every department had a game plan and I don’t think we could have pulled it off without the director and producers willing to pay us to be part of the rehearsal process.

There were many curveballs thrown along the way. One such curveball was an overhead LED light array that Chivo, our talented DP, wanted to use as his primary source in the St. James Theatre. This location was to be used for about three weeks of our schedule. The rig was quite amazing, a series of 12-inch by 12-inch LED panels, connected side by side and hung over the stage. This rig enabled Chivo to computer control the colors and effects of each panel separately. The problem with the rig was that each panel had a fan in it. Multiply that by 12 and you have 144 fans all hanging over the actors in a relatively quiet theater. I stumbled upon this rig one day as they were setting it up to test it.

This LED panel Chivo liked would mean looping the dialog, which Alejandro and I did not want. The producers thought I was being overly demanding until they learned that this same problem existed with the LED lighting rig used on Gravity, resulting in a lot of ADR.

They initiated a series of LED light tests, costing a fair amount of money with additional time and manpower. In the end, they found a company that manufactured a similar system that Chivo liked where all the fans could be switched off without the panels overheating. Many thanks to the producers for paying for these tests. I am extremely grateful to the grip and electric crews who always gave us a hand when needed. Their professionalism and talent never went unrecognized by my department and was a contributing factor in Chivo’s Oscar win for cinematography.

We can only record what is in the room; if the room is noisy, our recordings include that noise. It doesn’t make a difference what mics you use. All of the subtleties of the human voice; the quiet breaths and sighs, the minute details, all add to the effectiveness of a performance. It is our job to capture it to the best of our ability, even if that means risking popularity. In the end, we can only hope that the battles we fight are appreciated.

Every day on Birdman was basically one shot. We would rehearse for six hours, eat lunch and shoot take after take until all the elements came together. It was the first time in my career that after breakfast, we could safely say, “Martini’s up.”

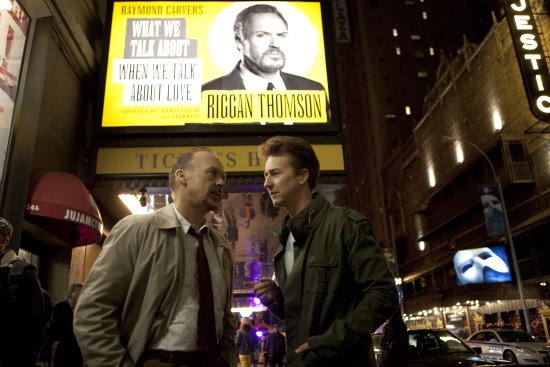

While each day posed a new set of challenges, there was one shot in particular that my crew was very proud of. It is when Riggan (Keaton) comes into the main entrance of the theater from outside, only in his underwear, so wiring him was not an option. The camera covered four areas. In rehearsals, I decided that we would need a third wireless boom operator. Luckily, our wonderful line producer approved that request.

The third Boom Operator, Teferra McKenzie, was waiting in the entrance and there was a plant mic for the actress behind the ticket booth. Teferra covered Riggan in the first room and was able to let the camera sneak through a narrow doorway before entering the room and covering four other actors. We had another plant on the arm of the wheelchair. Once Riggan opens the door to the theater, I cross fade to Brendan, booming Riggan as the camera is over Riggan’s shoulder at the stage. Brendan boomed Riggan’s lines until the camera pulls a quick 180, revealing where Riggan came in. At this point, Brendan has no chance of clearing the shot. We got him in wardrobe and left him in the scene. During this four-second pan, Brendan has to grab a line, then move into a sitting position and hide his pole behind several extras sitting in the same row. While Brendan is doing this, Adam Sanchez is fully extended with a twenty-two-foot pole on stage behind the curtains. The moment the camera pans off the stage, I cue Adam to move, Brendan sits and Adam sprints down a set of stairs into position over Riggan. Cross fading to Adam’s pole, the boom handoff was very fast and we were lucky to get what we did. Adam had to continue with a couple of 360-degree moves around the actors. This also required another magic disappearing act off stage somewhere. Sound magic; it all worked, but only by fractions of a second.

Birdman was a collaborative effort. There were many talented sound people in all the stages of post production. It’s wonderful to know that the tracks you work so hard for are going to safe and competent hands. Often, the problem with giving post so many tracks is that they don’t know how to build them as you intended. The Birdman post crew did great justice to my production recordings, along with adding a brilliant sound design and final mix. To all my talented new friends that I had the pleasure of meeting during this awards season, thank you. It was a pleasure and let’s do it again soon.