by Brandon Loulias

I’ve spent most of my adult life working on film sets; from the Wild West of nonunion indie movies to long-form narrative films and TV. It was a great way to collect experience. I also observed a common duality for most of us on regular shows: long hours, unpredictable wrap times, exhaustion, etc. Once the pandemic hit, it gave us an opportunity to reframe our lives and what we feel is important. I learned there are more things in life than living on a film set. This was a major shift for me, as I had never put a priority on my personal life. I took that time to reconfigure. The variety of work I’d get called for expanded vastly, from primarily narrative work to about ten different styles of sound work on large-scale productions with varying complexities. My post-sound career rekindled as well, which has always been a part of my life and I’ve always kept a mixing room wherever I’ve been for the past twenty years. These days, many of us don’t get the chance to choose the type of work we do. We either take the job, or someone else will and who knows when the next one will come. Regardless of the job requirements, I show up and solve problems, like any of us. I enjoy working in all the different disciplines under and around our little umbrella, albeit sometimes exhausting.

Most of my career has been by the seat of my pants, with gear manuals and internet access keeping me honest and employed since I was a kid. I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t know everything and never will. That’s the joy of this line of work for me. I’m a lifelong student of the crafts and the people around me as long as there’s something new to learn. Our employment depends on relationships, and good gear allows you to be with people instead of all the toys. The point of our equipment is to get it out of the way and be present for the process.

Once upon a time, a sound person could choose a particular discipline and stay within that classification for an entire career if they chose to do so. Things have changed a bit, and now many of our members will take what they can get in any classification. When I got into the union, my intention was to keep mixing. Alas, I was 6’7” and in my twenties, so they gave me a boom pole instead. Booming taught me to navigate and collaborate with other departments, which is vital to achieving a great soundtrack and a positive work environment. Coincidentally, I had to give up booming for health reasons, which has led me to be more dynamic in my skill sets to stay busy.

One thing I love about day playing is the ability to bounce between different workflows and avoid complacency with a particular job. The downside is having to pivot on a dime and sometimes even wearing different hats with variable complexity for each day of the week. There’s also the turnaround issue; like having a split-call mixing job that goes late one day, and an early call on a playback job with a completely different gear package the following morning. Most of the time, we just have to tough it out and be exhausted, as we may not have another job for a long time.

A double-edged sword of working in many disciplines is the need for multiple rigs that do multiple things. I believe in being prepared but will only purchase things out of necessity. Otherwise, we’ll just get into a loop of buying gear to make money to buy gear, which is a dangerous game I’ve been playing for most of my life.

I look at all jobs like a math equation; the problem is what the job requires, and the solution is something we provide through technology and skillful planning. Here are a few examples of problems I’ve encountered in the past few years, and what solutions I devised as a result. A huge benefactor in audio solutions these days is how technology has evolved. I am ever-so-grateful for many of the audio-over-IP solutions that I can rely on for all the mission-critical applications.

Then of course, the most important parts, like batteries and wheels.

Music Recording and Pro Tools Playback on Movies and TV

There’s been an increasing demand for recording live music on movies and TV, and I happen to get a lot of those calls lately. Here’s how I handle them:

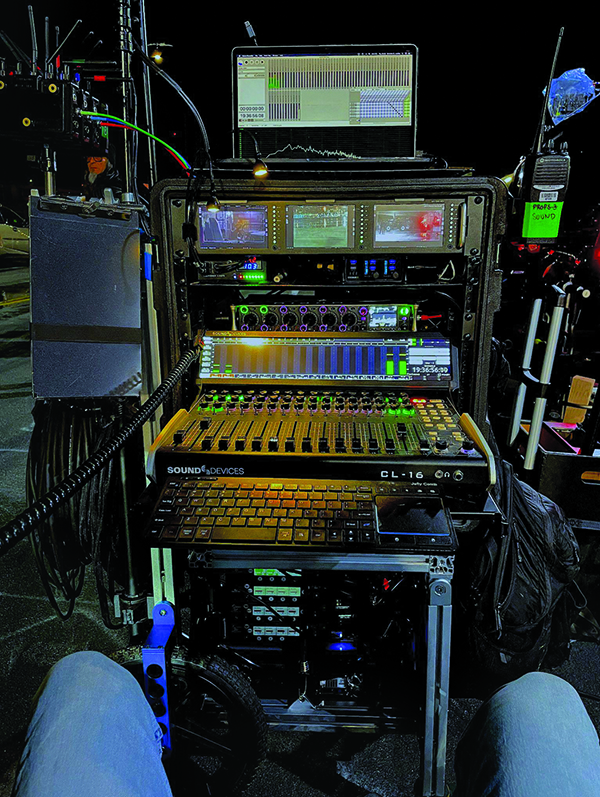

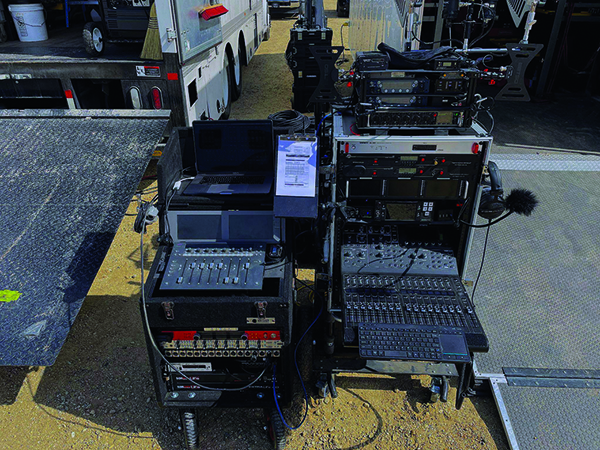

I ask for a tech rider, which gives me all the info like track lists, instruments, IEM requirements, mic choices, etc. I contact props and set dec, who are most likely already in touch with the stage and equipment companies, to determine who’s supplying the backline, stage tech, etc. A lot of the time, those companies will also provide additional workforce such as FOH mixers, A2’s, System Techs, etc. I always advocate getting additional A2 labor through Local 695 if we’re short on hands. I also like to have Pro Tools playback and band recording as two separate people if possible and the situation calls for it, although sometimes it has to be one. I have modular rigs that can accommodate both workflows via AES50 and Dante interchangeably. The flexibility of those interfaces gives me lots of options in various situations, and the Midas ecosystem is excellent for accommodating demanding and ever-changing workflows. I still use the good old Sound Devices 970 for large track counts, the Midas M32R & M32C mixers, and DL16 & DL32 stage boxes. Moving forward toward the shoot, I always ask for a rehearsal/pre-record day, if we can. It’s really nice when we can focus on recording with the artist on a click track, dial in IEM’s, and get a few clean takes without the hassle of “getting this next shot before lunch.”

I worked on Yellowstone S5 for a minute, where there was a frequent need for live-music recordings throughout the season. I put the bat signal out to production about needing to connect with the backline company, and they hooked me up with Alex Bruce from Montana Pro Audio, who was an absolute champion about it. He and his team built the stage and got the instruments, and we combined our mic collections to facilitate the needs of recording for all the bands.

I had to revise my system after the first round, as we were spread out on a ranch with a thumper for four hundred cowboys, and the band was in a tent with about five cameras floating around the premises. I returned with a smaller rig to do it all quickly and lightly. The coolest part is the mixer being able to jump between Midas and Pro Tools control at the push of a button, which proved extremely handy when recording thirty-two isos to play back on a dime against a thump with immediate turnover. I had a previous commitment, so my friend Nick Ronzio stepped in and finished the season on my rig. All went smoothly. A perfect reminder that simplicity, even with great technology, is sometimes the best choice.

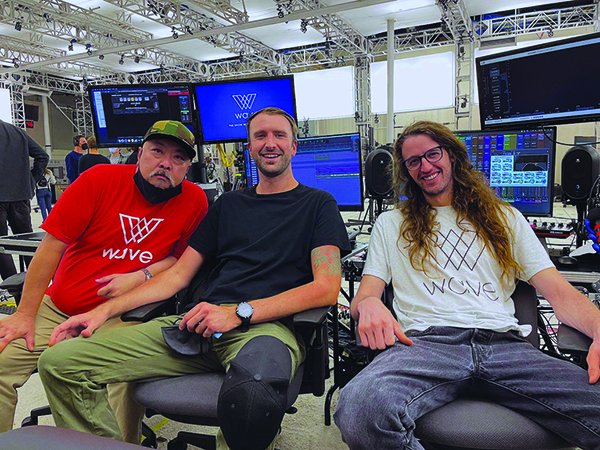

Live Broadcast Mixing for Justin Bieber’s Virtual Concert with Unreal Engine for WAVE

I was hired to create a sound ecosystem for live broadcast motion-capture virtual concerts using Unreal Engine and various DAW’s. This is how we did it:

The problem we faced was a live concert in real-time with Justin Bieber in a motion- and face-capture suit driving an avatar in Unreal Engine. This was broadcast to millions of viewers. The solution was a lot of rehearsals, MIDI cue points, math equations, and headaches. I built a system that can drive Unreal Engine from Pro Tools through MIDI, LTC timecode, and GPIO. This information was generated by Pro Tools with stems for monitoring, as well as crowd interaction and FX triggering via Ableton Live.

It all interfaced with Unreal and the BTS camera for live picture-in-picture, and everything was in tri-level sync feeding a TriCaster.

Some of the issues we faced in this process were calibrating the synchronization between various peripherals, even down to house sync and black burst. The face motion capture was about 23ms offset from body capture, which had to be ironed out by employing certain system delays. This also meant we needed to delay the audio by 384ms while still having the music in real-time for Bieber to perform. It ended up requiring a lot of different bussing and variable delays, including audio reactivity, which altered the lighting and graphics in the Unreal universe according to music intensity.

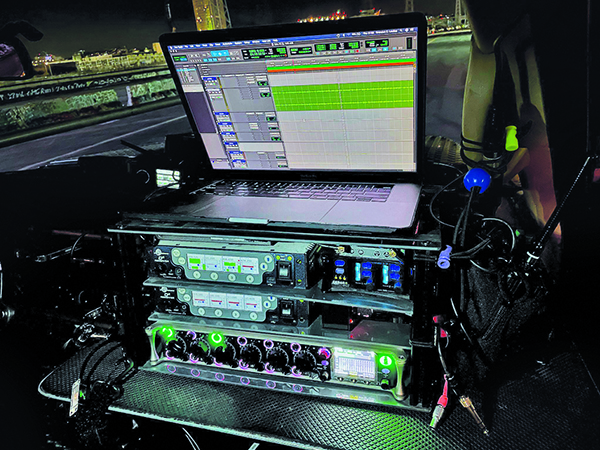

We developed a method for global sync calibration, where a technician wore the suit while moving to the beat and counted out loud so we could line up the body, face, and audio for all moving parts. We ran it for the duration of the concert to verify any detectable drift and cross-checked it with a 2-pop at the beginning and end of the show. All interconnects for our department were done using Dante and NDI on four computers. We had two identical Pro Tools HDX systems—one for playback and one for mixing. The other two computers were for systems management and crowd/FX triggers via Ableton. We controlled everything with two Avid S3’s, interfaced with Focusrite Red 8Pre’s, and recorded the whole thing on the good old Sound Devices 970. The result was music playback driving all visual cues and scenes within Unreal Engine while Bieber wore the suit to drive his avatar in that world. I got to work with one of my childhood best friends on this one, Will Thoren. This job was technologically ambitious and great to share together. It was also a good lesson in staying organized when it’s necessary to go big with our rigs.

Dolby Atmos Comedy Show in Dane Cook’s Backyard

Lately, I’ve been working in the niche circuit of live comedy, and we have a system for turning over Atmos-deliverable recordings. Here’s how:

My friend Thomas Cassetta does quite a lot of this work, and we usually do a lot of the production and post-sound on these together. On this one, I was the Production Mixer and Supervising Sound Editor, and he was the Re-recording Mixer. I’ve always found it to be an informative process to do both. Tom is a stellar colleague, and a pleasure to work with.

On live comedy, we like to use the Midas M32/970 workflow and boom recorder as backup. I’ve had a lot of success with those machines for higher track counts where you can’t have anything fail and millions of people are watching. Live comedy is a similar idea. My rig for this is fairly basic and the workload generally goes into hanging mics. On the Dane Cook special, we had to pull many stops as he wanted to do the special in an unusual place—his backyard. His house was in the Hollywood Hills, so loading in and logistics were an absolute nightmare for all involved. Luckily, he owned the house across the street as well, so we ran our base of operations from there over fiber on a crossover.

My main challenge was getting a full-sized LCR line array PA system to Dane’s top balcony while I was three stories down in his garage recording and mixing. Another thing was wind protection for twenty-six crowd mics. We rigged a combination of wired and wireless mics, hanging in spaced pairs along the perimeter, and an Ambisonic mic from above. We had the post contract on this, so any mess we made was ours to clean up. The game is to get full-bodied crowd sounds with all mics in sync and to run the PA quietly to give you enough separation in post for control. We had a Shure Axient System for his handhelds and Midas DL32 on the side of the stage, feeding into a Midas M32 at the FOH mix position via AES50. We daisy-chained the FOH to me downstairs in the garage on my Midas M32R into three backup recorders via Dante. This was a cool configuration as I could set the master trim and preamp controls from my mixer, and my FOH guy could do trims and such upstairs.

One thing I love about comedy stuff is prep days; you’d never see that on a film set. It’s also been a real pleasure meeting the other factions of A2’s and comms people who are 695 members—usually, we’d never cross paths. They are

highly intelligent, great to work with, and quite skilled. This gig showed me the importance of offline technical prep so that life can be easier on the day.

Pro Tools Playback Motion Control Workflow: The Flight Attendant S2

I first got the call for The Flight Attendant to solve a tech issue. They wanted to “parent-trap,” which is where you have one actor play many characters in the same shot. Here’s how:

We stacked Kaley Cuoco’s performances in QTAKE, and by the time we wrapped the scene, had a complete sequence. They were all layered in on a VFX comp, with only her dialog heard from each performance. This was important for VFX as some of the scenes had to have perfect eyelines, throw stacks of paper, high fives, etc. The dialog timing had to be on point as it would motivate the moves, and there needed to be enough of a gap for each line, otherwise, it would throw her off.

This required a repeatable scene. My system would drive six or more peripherals that employed motion control for the camera, QTAKE auto-record and layering, DMX lighting cues, and sound FX on the Pro Tools timeline. I decided to run it with record-run timecode via an Avid Sync HD, and I’d record the isos over Dante into Pro Tools HDX and on a 970. I chose LTC over GPIO to drive this, given the nature of linear time frames of each scene—hitting cues at certain intervals for FX, actions, light, and not to mention the flow of dialog. GPIO had only basic transport functions, and LTC allowed me to adjust things in my repeatable timeline. Each segment would start at 00:59:56:00 so as to give everything enough time to catch sync.

We wired everyone, including the photo doubles, who ran lines to hold space for when Cuoco was to do those character’s performances. I ran a Dante feed from the production mixer’s rig so I could get anything I wanted over that line, including the mix and all isos. I would roll when they called action, kicking the LTC off, which would trigger QTAKE to roll four cameras, the bloop light for Moco would hit at 01:00:00:00, our AD would call out “three … two … one … action,” then they’d do the scene. We wrote motion control, focus racks, DMX lighting cues, and any other chronological scene information against my LTC stripe on all moving parts, recording all data. If we wanted another one, we’d have to write it all again based on the linear requirements of the scenes. After we got a keeper-take, we would then call that the base on which we would build. I would mark that in my session, then figure out which character would go next. I would clean up the dialog on the fly with iZotope and cut out photo double lines of the character she chose to play next, so she could perform it. Sometimes we’d rehearse while she was getting wired, and she would read her next character’s lines against the other lines to practice timing. I’d also retain the verbal “three … two … one” cue, although it was archaic, as it served the purpose of cueing everyone on the exact same start mark each time for the scene.

We had to drive QTAKE’s initial “keeper-take” to play back in sync with the new one and print both into a new VFX comp track. We were effectively “stacking” performances, similar to a sequencer or multitracking in a DAW. I also would run my updated dialog edit into the mixer’s board, so it would always represent the most recent dialog comp for VTR overlays. Sometimes, I’d cue three beeps to help give her a start mark if her character didn’t start the scene or if she needed a cue for action. This was a constant process throughout the season, requiring all departments’ collaboration. It was great practice in how to translate weirdly complex situations to others in a palatable fashion.

To Leslie: Good Old-Fashioned Filmmaking

To Leslie was a special experience for me and a total relief from all the other deeply technological jobs I had gotten myself into. Shot single-camera on film, this job was fun because it wasn’t about big tough problem-solving or new fancy wireless gear; it was about the relationships and organic processes of capturing great performances. It was classical filmmaking. Our Director, Michael Morris, was an absolute joy to collaborate with. From the beginning, we discussed the music as it was important in this film. He left me in charge of the jukebox, and I was always ready whenever he wanted something for needle-drop or otherwise. It was very enjoyable to delve into the “outlaw country” discography and learn about a style of music I hadn’t been entirely familiar with. Some songs helped convey feelings and underlying subtexts in particular circumstances. While other times, it was about creating the right vibe.

Then there was Andrea Riseborough, who immediately caught me off guard and blew me away with her performance from day one. It was amazing to witness this powerhouse of a character, which shook most of us to the core. She had incredible dynamics, and keeping up with that was quite a task at times. Luckily, I had a killer crew of Johnny Kubelka as Boom Operator, and Dan Kelly as Utility. It was a real treat to have them both, Swiss Army knife-generation sound guys who have worked in many disciplines as well. We shot all over L.A. and out in the desert, all on location. It truly reminded me of the good old independent film days that felt like summer camp. Just filmmakers having fun.

No matter the application, it’s safe to say that our job requirements are evolving, and so are we. The amount of gear we have to keep is staggeringly more than ever, and we have to support each other to keep our rates up to accommodate for that. The gear is there to supplement our solutions, not to define us or our workflow. It doesn’t matter if you use Shure or Lectro, Zaxcom, Sound Devices, Cantar, Sonosax or Zoom—what matters is that we know how to use our equipment and adapt to the ever-changing landscape. A mixer’s gear loadout is reminiscent of their mind and what makes sense to them. We mustn’t forget the purpose of the gear is to get it out of the way and don’t forget to step away and live life.