Overview

The past ninety years of sound recording for motion picture production has seen a steady evolution in regards to the technologies used both on set and in studios for post production. Formats used for recording sound have changed markedly over the years (with the major transitions being the move away from optical soundtracks to analog magnetic recording, and from analog magnetic to digital magnetic formats, and finally, to file-based recording). Along with these changes, there has been a steady progression in the mixing equipment used both on set for production sound, as well as re-recording. Beginning with fairly crude two input mixers in the late 1920’s, up to current digital consoles boasting ninety-six or more inputs, mixing consoles have seen vast changes in both their capabilities and technology used within. In the article, we will take a look at the evolution of mixing equipment, and how it has impacted recording styles.

In The Beginning

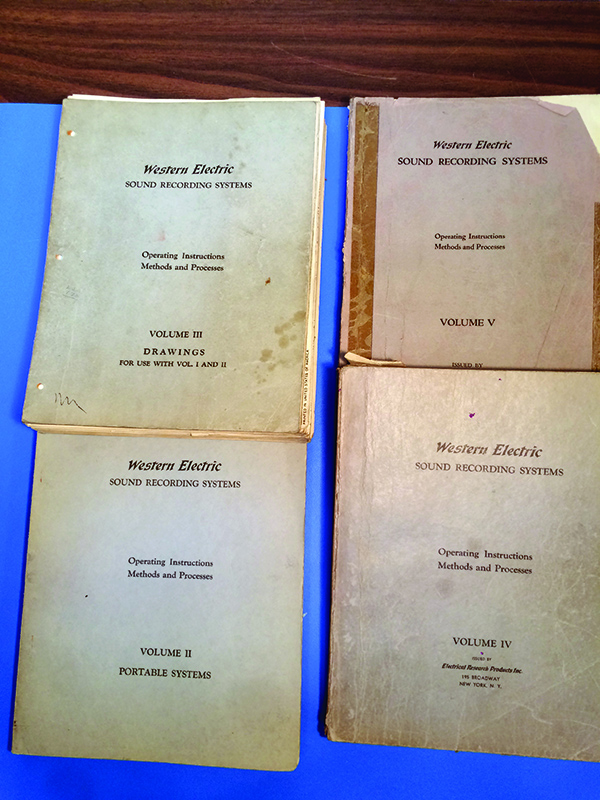

If you were a production mixer in the early 1930’s, you didn’t have a lot of choices when it came to sound mixing equipment. For starters, there were only two manufacturers, Western Electric and RCA. Studios did not own the equipment. Instead, it was leased from the manufacturers, and the studio paid a licensing fee for the use of the equipment (readily evidenced by the inclusion of either “Western Electric Sound Recording” or “Recorded by RCA Photophone Sound System” in the end credits). Both the equipment, as well as the related operating manuals, were tightly controlled by the manufacturers. For example, Western Electric manuals had serial numbers assigned to them, corresponding to the equipment on lease by the studio. These were large multi-volume manuals, consisting of hundreds of pages of detailed operating instructions, schematics, and related drawings. If you didn’t work at a major studio, there is no way you would even be able to obtain the manuals (much less comprehend their contents).

Early on, both Western Electric and RCA established operations that were specifically dedicated to sound recording for film, with sales and support operations located in Hollywood and New York. Manufacturing for RCA was done at its Camden, NJ, facilities. Western Electric opted to do its initial manufacturing at both the huge Hawthorne Works facility on the south side of Chicago, as well as its Kearny, New Jersey, plant. These facilities employed thousands of people already engaged in the manufacturing of telephone and early sound reinforcement equipment, as well as related manufacturing of vacuum tubes and other components used in sound equipment.

The engineering design for early sound equipment was done by engineers who came out of sound reinforcement and telephony design and manufacturing, as these areas of endeavor already had shared technologies related to speech transmission equipment. (Optical sound recording was still in its infancy at this stage though, and required a completely different set of engineering skills.)

With the rapid adoption of sound by the major studios beginning in April 1928 (post The Jazz Singer), there was no time for manufacturers to develop equipment from the ground up. If they were to establish and maintain a foothold in the motion picture business, they had to move as quickly as possible. Due to the high cost and complexities of manufacturing, engineers were encouraged by management to adapt existing design approaches used for broadcast and speech reinforcement equipment, as well as disc recording, to the needs of the motion picture business. As such, it was not unusual to see mixing and amplifier equipment designed for broadcast and speech reinforcement show up in a modified form for film recording.

Examples of these shared technologies are evident in nearly all of the equipment manufactured by both RCA and Western Electric (operating under their Electrical Research Products division). While equipment such as optical recorders and related technology had to be designed from the ground up, when it came to amplifiers, mixers’ microphones and speakers, manufacturers opted to adapt what they could from their current product lineup to the needs of the motion picture sound field. This is particularly evident in the equipment manufactured by RCA, which had shared manufacturing facilities for sound mixing equipment, microphones, loudspeakers and related technology used in the broadcast and sound reinforcement fields.

It was not unusual to see equipment originally designed for broadcast (and later, music recording) show up in the catalogs of equipment for film sound recording all the way through the early 1970’s.

Design Approaches

While the amplifier technology used in early sound mixing equipment varied somewhat between manufacturers, much of the overall operational design philosophy for film sound mixers remained the same all the way up through the mid to late 1950’s, when the stranglehold that RCA and Western Electric had on motion picture business began to be eaten away by the development of magnetic recording. (The sole standout being Fox, who had developed its own Fox-Movietone system.) New magnetic technologies (first developed by AEG in Germany in 1935), began gaining a foothold after the end of WWII, and players such as Ampex, Nagra, Magnecord, Magnasync, Magna-Tech, Fairchild, Stancil-Hoffman, Rangertone, Bach-Auricon, and others began to enter the field. Unlike RCA and Western Electric, these manufacturers were willing to sell their equipment outright to studios, and didn’t demand the licensing fees that were associated with the leasing arrangements of RCA and Western Electric.

Despite these advances, RCA and Western Electric were still the major suppliers for most film sound recording equipment for major studios well into the mid-sixties and early seventies, with upgraded versions of their optical recorders (which had been developed at significant cost) in the late 1940’s still being used to strike optical soundtracks for release prints. Both RCA and Western Electric developed “modification kits” for their existing dubbers and recorders, whereby mag heads and the associated electronics were added to film transports, thereby alleviating the cost of a wholesale replacement of all the film transport equipment. Much of this equipment remained in use at many facilities up until the 1970’s, when studios began taking advantage of high-speed dubbers with reverse capabilities.

The 1940’s

After the initial rush to marry sound to motion pictures, the 1940’s saw a steady series of improvements in film sound recording, mostly related to optical sound recording systems and solving problems related to synchronous filming on set, such as camera noise, arc light noise, poor acoustics, and related issues. In 1935, Siemens in Germany had developed a directional microphone which provided a solution to sounds coming from off set.

Disney also released the movie Fantasia, a groundbreaking achievement that featured the first commercial use of multi-channel surround sound in the theater. Using eight(!) channels of interlocked optical sound recorders for the recording of the music score and numerous equipment designs churned out by engineers at RCA, it can safely be said that the “Fantasound” system represented the most significant advance in film sound during the 1940’s. However, except for the development of the three-channel (L/C/R) panpot, the basic technology utilized for the mixing consoles remained mostly unchanged.

Likewise, functionality of standard mixing equipment for production sound saw few advances, except for much-needed improvements to amplifier technology (primarily in relation to problems due to microphonics in early tube designs). Re-recording consoles, however, began to see some changes, mostly in regards to equalization. Some studios began increasing the count of dubbers as well, which required an increase in the number of inputs required. For the most part, though, the basic operations of film sound recording and re-recording remained as they were in the previous decade.

The 1950’s

While manufacturers such as RCA and Western Electric attempted to extend the useful life of the optical sound equipment that they had sunk a significant amount of development money into, by the late 1950’s, the technology for production sound recording had already begun making the transition to ¼” tape with the introduction of the Nagra III recorder. Though other manufacturers such as Ampex, Rangertone, Scully, RCA, and Fairchild had also adapted some of their ¼” magnetic recorders for sync capability, all of these machines were essentially studio recorders that simply had sync heads fitted to them. While the introduction of magnetic recording significantly improved the quality of sound recording, it would remain for Stefan Kudelski to introduce the first truly lightweight battery-operated recorder capable of high-quality recording, based on the recorders that he originally designed for broadcast field recording. This was a complete game-changer, and eliminated the need for a sprocketed film recorder or studio tape machine to be located off-set somewhere (frequently in a truck), with the attendant need for and AC power or bulky battery boxes and inverters.

Later, Uher and Stellevox would also introduce similar battery- operated ¼” recorders that could also record sync sound. Up until this point, standard production mixing equipment had changed little in terms of design philosophies from the equipment initially developed in the early 1930’s (with the exception being some of the mixing equipment developed for early stereo recording during the early 1950’s for movies such as The Robe). Despite the development of the Germanium transistor by Bell Laboratories in 1951, most (if not all) film sound recording equipment of the 1950’s was still of vacuum tube design. Not only did this equipment require a significant source of power for operation, they were, by nature, heavy and bulky as a result of the power transformers and audio transformers that were a standard feature of all vacuum tube audio designs. In addition, they produced a lot of heat!

Most “portable” mixers of the 1950’s were still based largely on broadcast consoles manufactured by RCA, Western Electric (ERPI), Altec, and Collins. Again, all of vacuum tube design. The first commercial solid-state recording console wouldn’t come around until 1964, designed by Rupert Neve. A replacement for the venerated Altec 1567A tube mixer didn’t appear until the introduction of the Altec 1592A in the 1970’s.

A common trait amongst all of these designs was that nearly all of them were four input mixers. The only EQ provided was a switchable LF rolloff or high-pass filter. There were typically, no pads or first stage mic preamp gain trim controls. The mic preamps typically had a significant amount of gain, required to compensate for the low output of most of the ribbon and dynamic mics utilized in film production at the time (while condenser mics existed, they also tended to have relatively low output as well).

All had rotary faders, usually made by Daven. And except for the three-channel mixers expressly designed for stereo recording in the 1950’s, all had a single mono output.

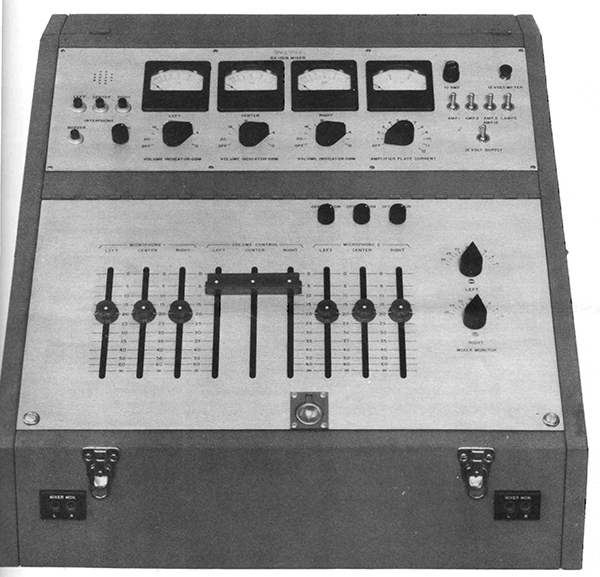

Re-recording consoles were of course much larger, with more facilities for equalization and other signal processing, but even these consoles seldom had more than eight to twelve inputs per section.

The 1960’s

While the 1950’s saw some significant advances in the technology of sound recording and reproduction, with the exception of the introduction of stereo sound (which was typically for CinemaScope roadshow releases), there had not been any really significant advances in recording methods since the transition from optical to magnetic recording. Power amplifiers and speaker systems had somewhat improved, boosting the performance of cinema reproduction. However, most mixing consoles relied on circuit topologies that were based on equipment from the 1940’s and 1950’s, with some minor improvements in dynamic range and signal-to-noise ratio.

It was during this period that technologies developed for music and broadcast began to seep into the area of film sound, and the approach to console designs began to change. The most notable shift was a move from the tube-based designs of the 1950’s to solid-state electronics, which significantly reduced the size and weight of portable consoles, and also for the first time, allowed for a design approach that could use batteries as a direct source of power, without the need for inverters or generators required to power traditional vacuum tube designs. This opened up a significant range of possibilities that had not existed before.

With the introduction of solid-state condenser mics, designers began to incorporate microphone powering as part their overall design approach to production mixers, which eliminated the need for cumbersome outboard power supplies.

Some mixers also began to include mic preamp gain trims as part the overall design approach (also borrowed from music consoles of the era), which made it easier to optimize the gain and fader settings for a particular microphone, and the dynamics of a scene.

The 1960’s would also see the introduction of straight-line faders (largely attributed to music engineer Tom Dowd during his stint at Atlantic Records in New York). In the film world, straight-line faders showed up first in re-recording consoles, which could occupy a larger “footprint.” However, they were slow to be adopted for production recording equipment. This was due in part to some resistance on the part of sound mixers who had grown up on rotary faders (with some good-sized bakelite knobs on them!), but also due to the fact that early wire-wound straight-line faders (such as Altec and Langevin) fared rather poorly in harsh conditions, requiring frequent cleaning.

Still, even by the end of the 1960’s, not much had changed in terms of the overall approach to production recording. Four input mixers were still the standard in most production sound setups, with little or no equalization. But the landscape was beginning to shift. While RCA and Westrex were still around, they had lost their dominance in the production world of film (although RCA still had a thriving business in theater sound service arena).

Things were about to change however.

Part 2 will continue in the next edition.

–Scott D. Smith CAS