Facing high-stakes challenges on a big-budget digital 3D feature film, Local 695 Engineer Ian Kelly makes it sound easy as he describes the unique production workflow he designed for the film Oz: The Great and Powerful.

by Ian Kelley

The way it was…

In the days of film, everyone knew what the workflow would be, from the producers to the lowliest camera assistant. Film went in the camera, was exposed and then sent off to the lab and everyone watched the dailies the next day. Sometimes magic happened, sometimes it didn’t. But for everyone, right through post, capturing the image and manipulating it had been refined over time right through to making release prints. Not anymore. New cameras and workflows emerge on a regular basis and unlike with film, there is no one correct way to make a movie. And added to that, the massive increase of visual effects means that ways to help the process have to be invented. 3D has further complicated workflows. Pity the poor producers with only a sketchy knowledge of the digital processes involved having to make very expensive decisions. For me, the most interesting part of a project is the design and the planning. It is the time when everyone’s needs on the production have to be assessed from what cameras are being used and what the deliverables are to what the workflow will have to be in order to accomplish the needs of the production through post. I usually try and map this out well ahead of time but it frequently changes as more information emerges.

Oz: The Great and Powerful

This film, which just wrapped principal photography, is a case in point. To be directed by Sam Raimi with Peter Deming as DP, it was to be a prequel to The Wizard of Oz and would be shot on recently completed soundstages in Pontiac, Michigan, thanks to generous tax incentives provided by the state of Michigan itself. Sam and his editor, Bob Murawski, are both from the area so that added an additional incentive to go there. My job was to be production video supervisor, a post I have occupied before on Alice in Wonderland for Tim Burton as well as The Polar Express, Beowulf and A Christmas Carol for Bob Zemeckis.

My work on the production began some three months before shooting began, starting with a test shoot in April of last year. For Oz, we tested both Red Epic and Arri Alexa 3D rigs. This was over three days at Universal on their new virtual stage and we tested cameras, recording systems and data management systems.

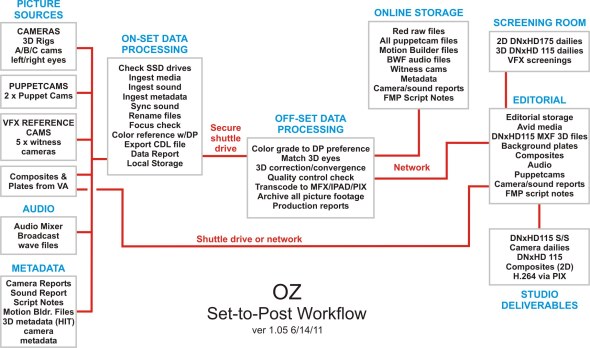

Once the test shoot was over and the dailies viewed, it was time to really start planning workflows for both cameras and recording and the data management once the shooting stopped. The DP obviously makes the decision as to which camera system but that will then dictate which hardware will need to be used and what software management systems will be used. Oz is a Disney film and the studio is very hands-on with regard to systems management so several meetings were held to discuss the best approach.

For the test, the Red Epics recorded to on-board SSD cards and the Alexa to a portable Codex recorder and there was considerable discussion about data management. For Alice, we had recorded to the big Codex studio deck and archived to LTO4 tape. I really like the virtual filing system on that deck although the machine is a bit of a boat anchor out in the field. Online storage was too expensive at that point (the movie was shot using Genesis and Dalsa cameras— file sizes were 8MB and 16MB per frame respectively) and largely untried to that date so the movie was completely tape based on LTO data tape, a somewhat painful way of working. For Oz, because of the number of VFX shots and the need to pull clips for turnovers on a weekly basis, it was decided that we would use online storage to keep all the media available although we were still going to archive to LTO5 data tape. For data management, we tested both FotoKem’s nextLAB and Light Iron Digitals’ OUTPOST systems. Both have their strengths but ultimately, we chose nextLAB.

For the actual shoot, it was decided that Panavision would supply three Red Epic 3D rigs plus two 2D Epic rigs—two on the 1st unit and one on the 2nd unit, with the 2D rigs for VFX shots such as reflection passes. Recording was to be on-board camera to SSD cards. Both units would have 3D video assist as well as 2D monitors for use on the set.

To add to the complications, there would also be three or more witness cameras and two remote recording booths for two of the characters who would later be animated with reference camera recordings made which would be used by the animators in post. Plus we had Encodacam that tracked the camera moves and drove Motion Builder backgrounds for real-time compositing—essential when so much of the movie was shot against blue screen. Both the composite and the background plates needed to be recorded.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Planning

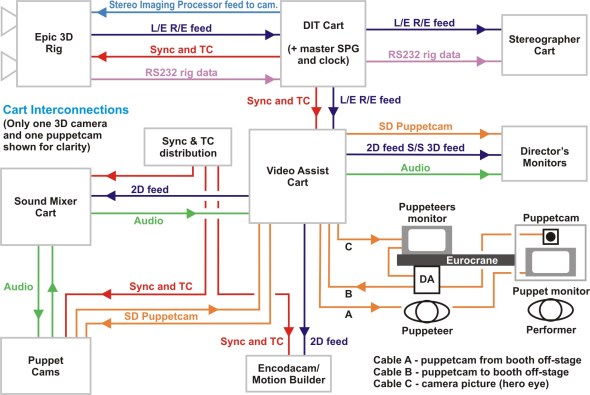

All of this has to be tied together in post of course, and this is where I insisted on the use of central sync and timecode for all cameras and recorders plus sound and witness cameras. This we achieved by using an Evertz 5600MSC master clock for each shooting unit with distribution amplifiers and patch panels built in to each DIT cart. We then made custom camera looms that carried sync and timecode, left- and right-eye pictures, return SIP (stereo imaging processor) feed and 3D rig control cables. I wanted to use fiber optic links to the cameras as we had done on Hugo but production ruled that out on expense grounds. As the movie was to be shot all on soundstages, that didn’t prove to be a big deal though. I did make “all-in-one” re-clocking boxes, for long cable runs, with BNCs on each side and AJA HD10DAs inside and these worked well.

I also wanted the different carts involved—DIT, stereographer, video assist, sound, Encodacam and puppetcam—to be tied together in a logical way, with a minimum of separate cables between them, to speed up setups. More cable looms and lots of sleeving later, I am now a familiar face at Pacific Radio in Burbank.

Prepping was done at Panavision through late May and June and much liaising was needed between camera, sound, video assist, VFX, Fotokem and Disney to make sure all the details were in place. We would be shooting in Pontiac—a long way from our usual suppliers of last-minute ‘stuff’—and Production wanted to know how much it would all cost. Finally, just after July 4, we loaded a 53-foot semi-trailer full to the brim with all the gear and sent it on its way.

Shooting crew

As well as the regular complement of Local 600 camera crew (who did a first-rate job of keeping all the gear organized), we had a DIT, a 3D rig technician and a stereographer for each unit. Working with DIT’s Ryan Nguyen, who I had previously worked with on Alice, and Paul Maletich, I pushed the idea of central sync and timecode distribution as that would really help our post workflow.

Originally, the color was to be graded after shooting (and after the SSD cards had been pulled from the cameras) but our DP wanted real-time color correction so Fotokem figured out a way to incorporate 3CP-created CDL file metadata into their workflow.

Kyle Spicer did media management on-set and Bryan and Eric from Fotokem did the work off-set in day and night shifts. All three did an excellent job.

The video assist was ably handled by the Local 695 team of Mike Herron and Roger Johnson on the main unit and Sam Harrison on the 2nd unit. Mike had opted for a Raptor 3D rig with four machines—one each for A and B cameras plus one for composites and one machine for playback reference. Mike could also drive the puppetcam recorder (also a Raptor 3D in dual recording mode) and the Encodacam background recorder with the big advantage that all the files were named and he could start and stop all of them centrally for playback to the director. Naming the files per the slate and take saved me hours in post!

Mike was kept extremely busy as Sam Raimi, our Director, made good use of video assist and of reference material from editorial as much of the movie had been storyboarded.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The witness cameras were handled by the VFX crew and were mainly used to provide shooting references for Sony Pictures Imageworks, who would be doing all the VFX work. These cameras all had Lockit boxes that were jammed on a regular basis so at least the timecodes were correct even if the files had to be named later. But the guys proved to be very good at slating shots and keeping good reports even if some of them were quite hilarious.

The puppetcam setup was very complicated. The idea was that the actors providing the voices and facial performances for the two animated characters would be outside the stages in a trailer with soundproof booths. They would watch the action taking place on stage on large-screen monitors via cameras mounted on lightweight Eurocranes cranes operated by puppeteers. It would be their character’s POV if you like. The on-stage actors would see the off-stage performers via small screens mounted on the crane arms under the cameras. The pictures came from Sony EX3 cameras mounted vertically in the booths. They shot performers via halfsilvered mirrors with the camera images flipped vertically, rather like a teleprompter arrangement. The pictures were recorded in HD and then downconverted to send to the set. It was a good idea and it worked quite well. But the twelve-foot-long Eurocranes, operated by puppeteers wearing Steadicam belts, were awkward and got in everyone’s way so we didn’t use them much. But we did use the HD recordings of the actors in the booths who mainly watched the shooting camera’s images. The director was able to watch their performances on the set as Mike, the video assist technician, was in full control of the Raptor HD recorders and could play back everything simultaneously.

We used Sony EX3 camers for all VFX-related reference material as they could take external tri-level sync and timecode. An early test I sent to Imageworks proved that Avid DNxHD115 files were quite acceptable and would be used for turning over shots. I could have hugged them all for that decision as conforming the original media to the editor’s cut would have been very painful.

Sound wasn’t a problem—it was well taken care of. Our sound mixer was Petur Hliddal from Local 695, who I had previously worked with on Batman Returns with Tim Burton and on Old School. And I’ve worked with Local 695 microphone boom operator Peggy Names many times—always a delight to work with. They were ably assisted by Local 695 members Gail Caroll Coe, also a microphone boom operator, and John DeMonaco, working as the utility sound technician.

What could possibly go wrong?

Well, first off, during prep, the Red Epic cameras would lose sync occasionally. The rig techs said they had a lot of trouble with this on a previous show and here it was happening again. I had my ’scope with me and, on checking the tri-level sync through the chain, all was well except for the output of the little Distribution Amp feeding the cameras. It was low, by .1 volt, despite getting the correct level in. I had a couple of little 1×2 D.A.s with me and they solved that problem.

It then transpired that the nextLAB system could not deal with AVI or Sony XDCAM files or transcode them. It ended up being my job to deal with any files that weren’t R3D files (which became known as Altmedia) and to transcode them to DNxHD115 using my Avid Media Composer and XDCAM transcoding software.

There is a common misconception that shooting digital means never having to say ‘cut’ as digital doesn’t cost money the way that film does. I had to explain to the producers that it takes 10 hours to archive one hour of material and that if we went over 2.4TB a day, simple arithmetic said that we would need more equipment and personnel or we wouldn’t keep up. That had the effect of concentrating people’s minds so that we returned to shooting an average of 1.5TB a day. All of this was archived on LTO5 tape and kept online on network-attached storage which ultimately reached a total of seven trays of 42TB each.

A further problem arose with our Red Epics. Latency became a big issue on some tightly operated shots. The minimum picture delay was two frames with the on-board Red display. To external displays, the delay could be up to five frames, depending on the monitor. I don’t think there is any way around this with 5K sensors and 2K monitoring with the current design of the camera. Our operators always managed to get the shot, although they had to be creative about anticipating movement.

Conclusions

We wrapped on December 22 after some 108 days of principal and four days of blue screen photography. Would I do it exactly the same way next time? Maybe. As I pointed out at the beginning of this article, there is no one ‘correct’ way to make a movie with digital cameras. Color correction on-set? Not necessarily. On Hugo, all color correction was done off-set as the DP was also the operator. Pre-built LUTs were used in Black Magic HD Link Pro boxes to approximate ‘the look’ that Bob Richardson wanted. And for 3D— should you converge on-set or shoot parallel and converge in post? Both ways are valid.

Technology is moving so rapidly that what was state-of-the-art six months ago isn’t necessarily so now. Techniques that weren’t available then are coming online all the time so ‘keeping up’ is essential. But not at the expense of risk. As I said to one of the producers— making a movie is like a swan sailing across a lake. You should be able to admire the artistry of the swan gliding along on the surface without any awareness of its little legs paddling away like crazy underneath. That’s our job, to make it look easy.