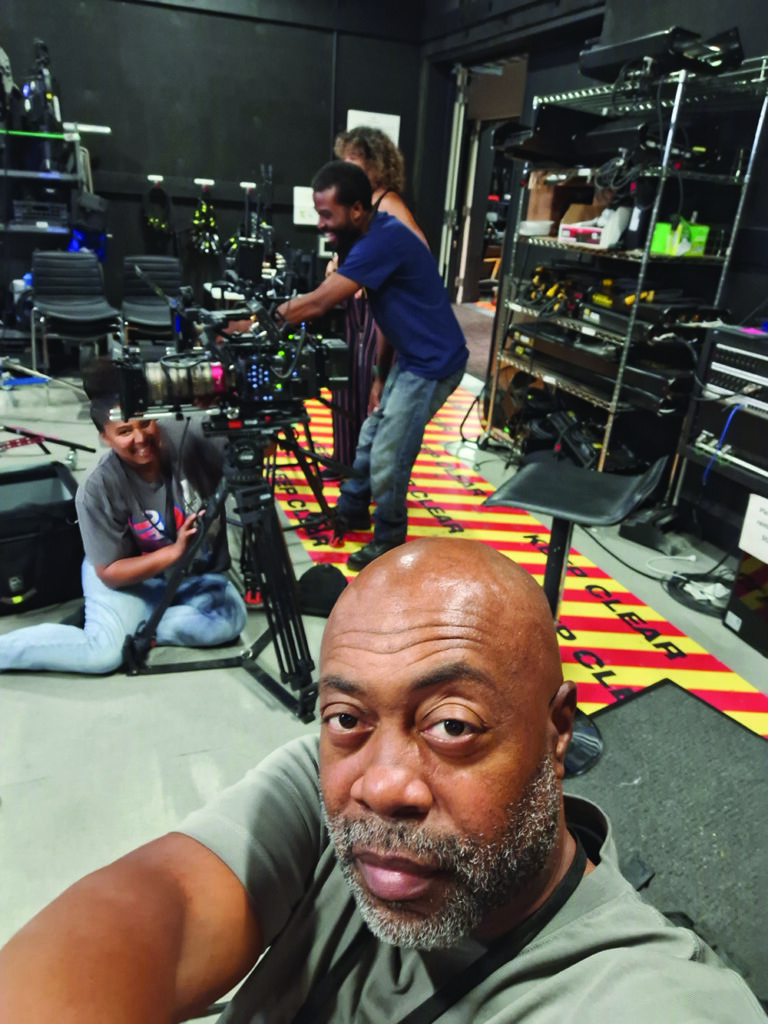

by Mr. Woody Stubblefield

There is no denying the allure of working on big-budget, AAA Hollywood productions. They pay well, they’re star-studded, and they have the power to transport audiences to worlds and realities completely unlike our own. However, not every production has the resources or the budget to tell stories at this scale. There is a whole world of creative and innovative stories being told on lower budgets and the filmmakers who thrive within these limitations are some of the best in the business.

Back in 1998, I was a music producer for Ice Cube and his music production company, Street Knowledge Productions. I was involved in the music videos for the songs I produced as on-camera talent, but had no idea that I would be pursuing a new path as a film production sound person for the next twenty years until one day, one of my childhood friends called. He had been a gang member, had been shot multiple times, and sold drugs to make a living. He called to ask me to do sound for his film project. I couldn’t imagine him having had any interest in filmmaking. He somehow got into USC’s film school and decided to do a film on one of South Central Los Angeles’s biggest drug lords, Freeway Ricky Ross, an older guy we knew well from the same neighborhood.

My friend approached me about doing sound for the film because he knew I did music and assumed this would be easy for me to do because, as he explained, “All it is, is a itty bitty mix board, and you already know how to work on the big boards, so you can do this!” I tried to talk my way out, but I couldn’t. I thought, well, I’ve damn near spent all of my royalty money and I’m doing some hustling in the streets that could go bad at some point so, I ended up in a production office on Melrose in a new environment of people, and trying to figure out how this relates to a movie. I met the Production Manager who explained how and why I was here and said I had no idea about what my childhood friend wanted me to do.

“I do rap music. I don’t know anything about this,” I told him.

He sat me down in front of a computer, which was the first time I touched a computer, and he pulled up a list of names and numbers. I ended up contacting Lionel Ball, a Production Sound Mixer—now deceased—and told him that if he taught me about sound in film, he could do my friend’s film and I would work with him. I started with Lionel making $50 a day for 18-hour workdays on low-budget projects. Some were lightweight porn, and some other low-budget shows. From there I started booming and I liked the set atmosphere enough that I decided to stick with it and see what could happen.

After years of booming for Lionel Ball, he would have projects that had one or two pick-up days and he would say, “You think you’re ready to get your feet wet? You know this stuff, you have the background, you can do it!” And there I was with a Mackie mixer, a 416 Sennheiser, and a DAT machine that Lionel loaned me to start me off. This was not like a recording studio, nor the protocols we use in the studio. I was advised by my mentors to not EQ the track. We only recorded in mono, not stereo. We used condenser mics and not dynamic mics for singing. We needed good strong clean recording levels. We didn’t mix the audio after it’s recorded to tape. All recordings were dry with no effects like we used in the studio. These were some of the things I had to adjust my thinking on.

Now I was at the helm of the mix ship. I was so active, battling with DPs who seemed to be causing obstacles to getting good sound and moving onto the next setup or scene without considering if I had good sound and if I was happy. I wasn’t having it. I became like Lionel Ball and Oliver Moss; fighting for good sound like it was my money being spent. I also started thinking it was my time to do things that I quietly thought my mentors should have been doing. Like most young people think, I figured I knew a little better. Still, after 20+ years in the game, I call my mentors Oliver Moss, Veda Cambell, and Reggie Dunn. There were also the technical guys like Mike Paul and Robert Anzalone at Location Sound and John Hicks at Trew Audio.

Of course, some helped me along the way as I started getting other sound jobs. In 1999, I was working on a movie and a Key Grip and Gaffer named Johnny Martin owned two big trucks full of equipment. I would be on set with my equipment set up on a folding lunch table from production. The boom guy and I would grab both ends of the table and move it to stay out of the shot or carry it from set to set. One day, Johnny came over and said, “Hey kid, I like you and I made something for you.” Johnny had the grips cut wood from the truck to create a tabletop shelf and attached it to what I later found out was a Magliner, so I could move around more easily. I was hella thankful. It felt like I was given a new Cadillac. At the end of the show, I rolled the cart back over to Johnny’s truck and he said “My gift to you, keep it.”

I was so damn happy, I rolled it over and started putting it in my back seat when one of the grips came over and said “Hey dude that goes in our truck.”

I said “Oh no, he gave it to me.”

In disbelief the grip said “No way dude, those cost a lot of money.”

I didn’t budge, so he went to Johnny as I loaded my new cart into the car. As I was in my car about to drive off, that same grip appeared once more and said, “Dude you’re one lucky mother F>>>>.”

I smiled and drove off. That Magliner is still my main cart to this day. And there was Frank at Coffey Sound, now deceased, who helped me stay in the game by renting me equipment by charging me for a single day on weeklong rentals. That helped me keep a little money in my pocket and have access to equipment that I couldn’t afford to own myself. Between Frank and Lionel, I was able to start acquiring my gear.

When you work on low-budget films, you don’t make enough money to invest in better equipment or even new equipment. I’ve worked on so many low-budget jobs where there wasn’t enough budget for wireless packs for every actor on set. I had to fight for time to get coverage of all the actors on the boom mic. I was taught that wireless was an aid to getting sound in wide master shots or shots where you just couldn’t get the boom in. Nowadays it kind of feels like the boom is the backup or the fill-in to the wireless mics. You work a lot harder on low-budget films because the producers and directors are trying to make a shoestring-budget film look like or feel like a multi-million-dollar film. Most of the time, those films look like the budget productions they are.

Low-budget films can allow you the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from those mistakes. I once had the opportunity to visit the post editor working on a project I recorded and boomed at the same time. I thought I had done a good job until he let me hear some takes and then allowed me to sit at the computer, line up the takes, and pick the best audio of all of the takes for the edit. I learned that I had recorded some bad audio that couldn’t be fixed in certain scenes, and the audio had to be discarded. The producers were going to be told that it was unusable and they would have to pay to have actors ADR the scenes or just go with what they had. I felt like crap. I learned that there’s more to sound recording than sticking the mic out there in any environment and expecting the recordings were going to be good or acceptable. Good sound in a low-budget film is just as critical as it is in a big-budget film. Good sound on a low budget can make that film worth watching. When I hear bad sound or bad moments of sound in a movie, I wonder what was the cause of that. To this day, I will still work with students from AFI, UCLA, USC, L.A. Film School, and some low-budget union projects of people whom I’ve met along the way trying to get their careers as a director or producer off the ground. In my first years of working on low budgets, I didn’t think about big-budget films. My focus was my call to do the job. The trust a producer had in me or heard from someone about me to be the one to call had me pumped as if I was on a big-budget film. I always felt like my work may make this project blow up like The Blair Witch Project or something. I thought if they can do it, this might be the one and I’m a part of it. It’s a pleasure for me to collaborate with these filmmakers in the creative process of bringing their projects to life and providing them with high-quality sound, and ensuring that they won’t need to spend excessively on post-production audio fixes due to skill and planning.

One bad thing about low-budget productions is they don’t have the budget to adequately fund each department according to what the script calls for. Why do they push ahead and come at us like “This is what we have and we don’t have anymore so you’re just going to have to make it work.” You have to at that point decide if moving forward will stress you and also hurt your reputation in the end.

One other bad thing about low-budget films is some start production without all of the funds in place and they’re not upfront about that with the crew. At some point, you will start to hear and see that there is a budget problem. Usually, you’ll overhear the producer’s issues or get wind of some of the crew members not getting their checks on payday. In low-budget films, there are a lot of young people and some seasoned folks who need to make some money to pay the bills. I remember one film where I was the line producer’s first call. They had budget issues. No one had gotten a check for three weeks. The crafty lady told me she was borrowing money for gas to get to the set. Crew members were counting on those checks because the money was already spent as soon as they cashed the check. I encouraged the younger folks on set who didn’t know what to do to have a conversation with the producers. They were scared and skeptical. Afraid of making a wave or being blackballed.

At lunchtime, I walked over to the producer’s table and said to them, “I think it would be good if you guys could speak to the crew about their pay, because most of them are saying they don’t want to work anymore if they don’t get paid.”

They talked to a few of the crew and I saw crew members walking away with unhappy faces. The line producer that hired me was paying my rental rate so I was a bit less alarmed even though I was missing three checks too. Then I started calling crew members passing by my cart to come over and tell me what happened. One young lady had tears in her eyes, so I went and talked to the grips about how they felt and we decided it was time to shut it down. I told them I would hold the sound for everyone until we all got paid. We held a meeting with the producers and let them know we were standing down. They were furious, except for one producer who was pretty understanding. Now everyone who was holding tension began to express their issues about not getting paid. They decided to wrap the day early.

My line producer came over to me and cursed me out. She said, “You’re getting some money, why are you doing this? I brought you on, you’re making me look bad. I’m getting blamed for bringing you on.”

I said that the kids needed their money. She said we were done. I was okay and not okay because we had done many projects together. The producers got the crew to agree to finish the project and, in the end, they understood that I would hold the sound for the rest of the shoot until they got the payroll to pay the crew even after we wrapped the show. So that’s what happened. A few days after we wrapped, everyone got a call to meet up at the production office to get their checks. Each crew member called me or texted me to say that they got all of their checks. I handed over the sound after being the last one to get checks. A crew member told me about the wrap party that I wasn’t invited to. I walked in and the looks on the producer and director’s faces said, “You really showed up, huh?” but as soon as the crew saw me, they cheered my name and clapped. The DP called me over and said “Honey, this is Woody, the guy who got us our money. Woody this is my wife.” He called for a beer for me, then a toast. We chilled and partied.

One thing I would like to see is, low-budget films not viewing the union as the bogeyman, coming to take the money that they could be spending on production or feeling contained. The lead-up to the production being “flipped” to union creates a tense vibe in production that spills out onto the set. I would like to see the ultra-low budget agreement or side letter agreement look identical to the basic agreement. Eventually, you want to work on the bigger budget films, so that you can purchase the latest equipment to help you with the advancing ways films are shot these days. You want to be able to see some equity from your labor. When you hear sound mixers talking about how they dropped 80 grand on extra equipment to rent back to production as a side business. How they own rental properties and drive cars costing over 50 grand; you want that too. And it’s not going to come from low budgets even though I did buy my house off a mixture of decent low- to no-budget projects. I bust my ass, often doing double shifts—wrapping one shoot at night, driving straight to the next set, sleeping in the parking lot until call time, and repeating this routine for days. That’s my spill on low budgets.