by Mark Weingarten CAS

It’s hard to believe that it’s been more than three years since I first began to write this article. A lot has occurred since then which either derailed and or postponed many of our plans. We started shooting Top Gun: Maverick in San Diego in May of 2018. We ultimately were in production for more than a year.

In 2018 during pre-production for Top Gun: Maverick, I met the film’s Director, Joseph (Joe) Kosinski. He explained that Top Gun: Maverick would not be a remake. It would be a standalone second act to the very successful Tony Scott-Jerry Bruckheimer-Tom Cruise-Val Kilmer film, Top Gun from 1986. Tom Cruise would be returning in the lead role as Maverick, and Val Kilmer would also be coming back to make an appearance as Ice Man.

In that meeting, I learned that Top Gun: Maverick would be shooting almost entirely in California, which is where I live. I had been shooting on distant locations for most of my projects over the preceding years. The opportunity to shoot a whole movie at home was very welcome.

I was very pleased when Joe and Executive Producer Tommy Harper decided to offer me the opportunity to be the Production Sound Mixer for Top Gun: Maverick. I could tell it was going to be exciting. It was going to present some very unusual problem-solving situations that would be rewarding to figure out, and it was going to be LOUD, REALLY LOUD! For certain, it was not going to be boring.

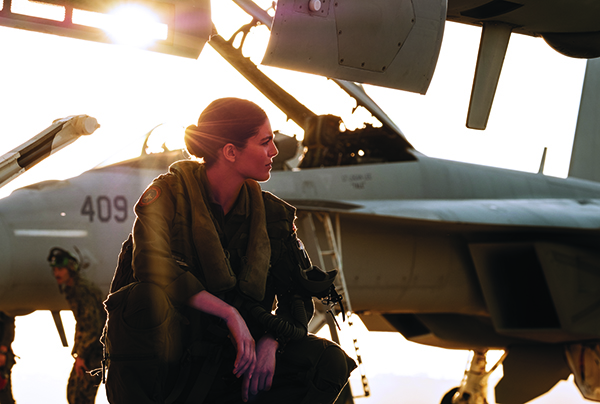

Joe and I discussed some of the major sound challenges that he knew we would face, and we kicked around what we thought might be the best approaches to tackling them. The most immediate issue to address was that we were going to film all the actors’ flying sequences actually inflight, real supersonic sorties while the actors and the sound equipment were being subjected to extreme G Forces. The request was for me to record all the inflight dialog in sync with the six cameras that would be mounted in the planes, with high-enough quality to be used in the final mix. There were to be no green screen-simulated flying sequences for this version! Everything was to be filmed actually in flight. I can’t say I had ever been asked to record in those conditions, but I was certainly game to give it a try… Going forward, I quickly learned that Joe was extremely calm, extremely prepared, and extremely supportive. He is an absolute pleasure to work with.

The TOPGUN Flying Team is a branch of the Navy. As such, we shot primarily at naval air stations. Those naval air stations are where the aircraft that we needed to shoot were hangared. We did shoot a little bit on stage at LA Center Studios, and also at some practical locations in and around Los Angeles and San Diego, but mostly we were at relatively distant locations all over California. It turned out that “shooting almost entirely in California” meant China Lake, San Diego, Lake Tahoe. To get to most of the naval air stations, it took a lot of driving, but at least I was able to make it home for most weekends.

We began shooting in May 2018 in San Diego for a one week pre-shoot at Coronado’s North Island Naval Air Station.

After the pre-shoot week, the whole crew went immediately into a couple of months of intensive scouting and prepping. During this time, all the departments scratched their heads and went hard at the work of figuring out how to approach filming and recording the flying sequences. We all had multiple scouting trips to several different naval air stations to look at, measure, inspect, and learn as much as we could about the F/A-18 supersonic jets that we would be using for filming.

Once each department determined what equipment they thought would be needed to do their inflight work, our Key Grip, the late Trevor Fulks, had to tackle how and where, to attach the equipment on the planes. We were told that any gear placed in the planes needed to be able to stay attached at up to 7G’s, and the gear could not interfere or prevent any aircraft functions or communications, nor could it interfere with the pilot or co-pilot’s ability to eject in an emergency situation if that ever became necessary. Having figured out how we could meet each of the Navy’s requirements, we began interacting with the Navy to submit our plans for their approval. We were asked to state every detail about each piece of gear: its purpose, its height, length, width, weight, the type of internal batteries it used, etc. The Navy had to sign off on exactly how and where we planned to mount each piece of our equipment for it to safely stay in place while the planes were in the air.

During scouting, we learned that in the Navy, all tasks are broken down and pieced out to very specific departments. Each department is referred to by its own specific abbreviated nickname. It took a lot of hunting to figure out which departments were responsible for exactly which functions. Each of these departments usually consists of a combination of naval personnel and civilian contractors. The mystery for me was which department(s) could provide me with the information that I would need to be able to figure out how to record our actors’ inflight dialog in a manner that would render it one hundred percent usable for the production? It took me many hours of scouting time to track down which departments were responsible for which aspects of the pilots’ communications: plane to plane, plane to ground, archiving of all the planes’ communications.

The planes have an internal communication system (Comms), which is fed to mics mounted inside of the pilot and co-pilot’s oxygen masks, and monitored by headsets built into their helmets. Who was in charge of the mics in the masks and the headsets in their helmets? How and where did the pilots connect the masks and helmets to the planes?

I learned that within the air station’s hangars, there are many doors. Each of these doors lead to the offices of one of the Navy’s various aircraft-related departments. Figuring out who did what and which unmarked door they were behind was both very time-consuming and very confusing. Eventually, I was able to find the right combination of departments to help me.

The mechanics were able to show me all the possible access points where I could tap into the plane’s Comms. Unfortunately, none of those access points would work for what I needed to do. I considered the possibility that I could record all of our planes’ transmissions from the ground (as the Navy does record all of their communications for archiving). However, the archive’s voice quality isn’t very good. Certainly not good enough to use for a final movie soundtrack.

Plus all of the Navy’s archived communications are classified, so it would be challenging to get clearances to use the recordings. Even if we were to receive clearance, trying to sync up all those un-slated recordings from all those flights would have been a nightmare. Obviously, this was not an option, the dialog had to be recorded in the plane while it was inflight at the highest quality possible, and it had to be available for us to be able to sync up and use immediately after each flight.

In addition to having the sound recording equipment properly secured to the aircraft, it was also imperative that its operation could not have any effect on the ability of the pilots’ mask to deliver oxygen to them at higher altitudes. Nor could it interfere with any communications between pilot and co-pilot. Given these restrictions, how could the inflight sound be safely captured, in sync, at the quality that the movie deserved?

During prep, I learned that there are specific connectors for fixed wing aircraft, and for helicopters, and that the wiring configurations for those connectors differ for the various branches of the service. All of the connectors involved in aeronautics are unique. They are connectors the likes of which I have never encountered before.

With guidance from the Navy and the help of the Parachute Room Team, I found the right place to tap into the plane’s Comms to be able to get the best possible inflight recording, while still allowing for uninterrupted communications, not interfering with the mask’s oxygen flow or compromising an emergency ejection.

I have made plenty of adaptor cables in my time, but considering the unfamiliar aircraft connectors and the absolute cannot fail operation of this mission-critical piece of equipment, I needed to seek out someone one hundred percent familiar with all of the elements involved to fabricate the Y cables I required. A Navy pilot introduced me to Par, at Pilot USA Communications. Pilot USA makes all sorts of cables and adaptors for all the branches of the military. I spoke with Par to explain all the specs for the Y cable I wanted him to fabricate. I explained that it was imperative that the cable would not interfere with any aircraft functions while being able to feed pure undistorted audio to two Lectrosonics transmitters via TA5F connectors; I would have a dual feed to two SM’s, in case failed. He asked me to draw up a wiring diagram. I sent him a very crude drawing of the cable, along with a copy of Lectrosonics TA5F wiring diagram. Par was able to read my drawing and understand it. He said he felt confident that he would be able to fabricate a Y cable that would meet all my requirements.

My initial concept for the flying sequences was to put two Lectrosonics SM transmitters on each actor, with two Lectro 411 receivers attached to a single recorder in the plane, and two additional mics attached somewhere inside the canopy for stereo sounds of the jet’s engines, rattles, and groans inflight. Four tracks would be enough to do the job so I chose a Sound Devices 744. I chose the 744 because it was the smallest four-channel recorder that I had, and because I thought it was one of the sturdiest, best built devices I knew of. I figured it was most likely to survive the potential forces of up to 7G’s. Given the intense G Forces involved, I thought it best to eliminate any moving parts. As such, I replaced the 744’s original spinning hard drive with a solid-state hard drive.

I brought the 744 and the 411’s to Trevor Fulks, for him to design and fabricate the mounts needed to secure them to the plane. While Trevor was doing that, I sent our Navy liaison all the requested specifications for the sound gear, which he forwarded to the appropriate Navy departments for approval.

Tom Cruise had requested that there would be a remote control in the plane that would give him the ability to start and cut all the cameras and the sound recorder simultaneously with a single button press. Keslow Camera was building the remote for the cameras. Dan Ming, our incredibly helpful A camera 1st AC, spoke with Keslow for me and they told him they thought it would be possible to incorporate record-stop control for the 744 into the remote. I sent Keslow a Sound Devices CL-1 remote control interface, along with the schematics for it. They were able to cannibalize the CL-1 and incorporate it successfully into the remote. Once completed, the remote worked perfectly. It was able to start and stop everything with a single button press.

The cameras we used were the Sony VENICE. They are large sensor, 6K, IMAX capable cameras. The VENICE lenses and sensors could be connected to each other by fiber optic cables. This gave them the capability for the lenses to be mounted separately from the camera bodies. Ultimately, the Camera and Grip Departments found that there was enough room to safely secure six cameras in each F/A-18. All six camera bodies were mounted in one cluster midway under the plane’s canopy. The separately mounted lenses were placed wherever was ideal for picture.

Curiously, we found that the camera bodies would fit better in one plane than another. We learned that no two plane canopies are the same; each one is handmade and is slightly different from any other.

Things were starting to come together. The Navy was reviewing our equipment lists. The remote was being made. The Y cables were being built. Trevor was fabricating the mounts to attach everyone’s gear to the planes. We just needed to get everything delivered in time to do a little testing before it would be needed for shooting.

The mounts, the Navy’s approval of the gear, and Keslow’s remote all arrived the week before we were to start shooting the flying sequences. In the hangar, we mounted all the cameras, as well as my recorder and radio receivers into an F/A-18. The Keslow remote worked perfectly, it reliably rolled and cut all the cameras together with the 744. We did one final shakedown test flight without an actor to make sure that everything Trevor had mounted for us stayed in place. It did. Unfortunately, the Y cables hadn’t arrived in time for that test flight. The next opportunity to test would not be until we started shooting, with an actor in the plane. Fingers crossed that the Y cable was going to work!

Time now for the rest of sound crew to come on board: Tom Huck Caton (Boom Operator), Cara Kovach (Utility to start), Kevin Becker (Utility to finish). Additional sound crew that worked on the film were Mark Agostino, Eric Ballew, Lawrence Commans, Jeff Haddad, Zach Wrobel, and Jeff Zimmerman.

Production officially started. The day had come for our first flight. Tom Cruise was fully suited up, the still untested Y cable had been connected by the indispensable Neville, a civilian contractor who worked for the PR Department. The SM’s were on, the 411’s were powered up, the 744 was awake with its timecode jammed to the same code as the cameras, and it was ready to record. Cruise climbed into the plane. There was silence. I heard absolutely nothing at the sound cart where I had tuned its receivers to the same frequencies as the 411’s in the plane. However, once the F/A-18’s system was energized, it came alive; I was able to hear through the Comms as the plane went through all its trouble warnings (it does this every time on startup) “engine fire,” “flap failure,” etc. When the warnings finally ended, Cruise spoke. I heard him loud and clear. Yes! The Y cable was working! Phew!

Soon after the F/A-18 Hornet took off, it disappeared and returned about an hour or so later. We retrieved all the media, brought it back to the hangar where we downloaded all the camera and sound files, backed them up, then brought the masters to the DIT for us to watch.

The pictures were spectacular. Claudio Miranda’s inflight cinematography is extraordinary. You can absolutely tell that the actors are really flying in the F/A-18’s, it is very clear they are not being shot against green screen. The Keslow remote worked perfectly throughout the flight. Cruise had been able to start and stop all the cameras, along with the sound recorder as he requested. The sound the Y cable provided was fantastic, crystal clear, absolutely, usable. A triumph. High fives all around… It turned out that on that very first sortie, the plane did, at some point, hit 7G’s, and nothing came loose. Trevor’s mounts worked perfectly, the 744, the 411’s and all the cameras and lenses remained solidly in place. In short, it worked. Everything worked!

Well, so we thought. During dailies, Cruise pointed out my 744 and the 411’s ended up very much in the frame. The sound gear had to move, however, I was told by Trevor that the sound gear was mounted in “the only place in the plane that it could be” and there was “no other option.” Even if we had been able to find an alternative mounting place, the Navy would have had to approve of that change, which would not be a quick process.

Lectrosonics PDR

What to do? We had a week to re-group before we were scheduled for our next flight. I went back to my on-base Navy housing to try to come up with a new strategy. The Day One flight had confirmed that the Y cable that Par had made worked perfectly, but without the 744 and 411’s, how could I capture the inflight dialog? The Y cables were built with two female TA5 connectors to feed two SM’s. I got on my laptop and began looking through the Lectrosonics website, and found that they made a little standalone recorder called a PDR. The PDR accepted a female TA5 for an input. There were two versions of the PDR. The single AAA battery model was almost identical in size to a single AA battery SM, and the PDR was capable of jamming timecode. It would record two tracks of WAV files onto a removable micro CF card at very high quality. Great! With a 16GB micro CF card, the PDR would easily record audio for many hours, certainly long enough to record any length of flight (sortie) we would be filming. According to the specs, the PDR would be able to make recordings of a quality similar to a 744. I immediately ordered two of them from Trew Audio. We found that indeed the PDR’s easily fit in exactly the same place where the SM’s had been. When attached to our existing Y cables, they should produce recordings equal in quality to the SM’s. Because they would be placed where the SM’s had been, they would not require Navy approval.

However, the change to the PDR’s meant that Cruise would lose the ability for remote-controlled starting and stopping of the sound recorder in flight. With the PDR’s, my plan was that just before the actors were to climb into their planes, either Huck or I would put the PDR’s into “record” and attach them to Y cable. This meant that the PDR’s would be recording continuously from that point on throughout the entire sortie. They would not stop recording until the plane was on the ground and one of us could retrieve the PDR to push “Stop.”

We explained to Cruise the switch to the PDR’s and the reason for it, and how the change would negate his ability to remotely start and stop the sound recorder. He completely understood the situation and was fine with it. I had never worked with him before. I found him to be extremely pleasant, reasonable, and fabulous throughout.

Our next batch of flying dailies demonstrated that the PDR’s worked perfectly. Their timecode was accurate, they synced up easily, continuously recorded throughout, regardless of G Forces or altitude and they sounded great.

After our initial single actor flights, we started having sorties with two planes taking off at the same time, sometimes with plane-to-plane dialog being recorded. We often had two planes going up in both morning and afternoon sorties. We needed more PDR’s and more Y cables. I ordered a bunch more of both. All the PDR’s performed impeccably. Of the literally hundreds of sorties, we only had one single PDR failure. Sometimes the sorties would last for hours, but no matter what, the PDR’s would keep on recording. We even had an instance, when because of a mechanical problem, the plane had to make a forced landing at a different naval air station and we weren’t able to retrieve that PDR until it returned the next day. Regardless, we were able to recover the previous day’s recording easily.

Among the many nice features of the PDR’s was their ability to record two mono tracks from a single input at two different levels. I would always record one track at a level a few db’s lower than the other track. If someone got really loud and started blowing the hotter track, the lower level track always stayed undistorted. OK, I can see that I’m starting to sound like a spokesman for Lectrosonics. I’m not, I have no affiliation, but I do love their products and obviously I am now especially enamored with the PDR.

Working around the planes, we learned that there was great concern about something the Navy called FOD, which stands for Foreign Object Damage. (Everything in the Navy is represented by an acronym.) Anything that could get loose in the cockpit inflight would be considered FOD. Any foreign entity on the runway that could potentially interfere with take-off or landing would also be considered FOD. We had to make sure nothing that we were attaching to the planes could ever turn into FOD.

For Navy airmen, every day begins with a “FOD walk.” The entire squadron lines up across the width of the runway and walks its entire length, eyes to the ground, retrieving pebbles, loose screws, etc. The Commander told us that each morning before the FOD walk, he would place a tiny brass button somewhere on the runway. If the brass button was not found and returned to him during the first sweep, he would order a second, then a third. Until that button was retrieved, no planes would be cleared to take off or land. They also do FOD walks every morning on all aircraft carriers. FOD is serious business.

It was surprisingly quiet inside the cockpits of our supersonic fighter planes. After the first flight, we listened back to the recordings from two FX mics I had mounted inside the plane’s cabin. They essentially recorded a steady flow of air. The extra mics weren’t really giving us much, and they posed the risk of possibly becoming FOD, I decided to abandon them. The mics in the pilot’s masks gave us perfectly acceptable sound whether their masks were open or closed. Ultimately, there was no a need to put a lav on the outside of their survival vests. Eliminating the lav and eliminating the FX mics enabled us to use only one PDR per actor, per flight. Given the FOD concerns, the less gear we put in the planes, the better.

I also did do a lot of stereo recordings on the ground; the planes starting and warming up, taxiing away, taxiing toward us, taking off, landing, and doing flyovers. Fighter jets are LOUD. I mean crazy LOUD!!! You can feel the heat from their afterburners even when they are nearly an entire runway length away.

The carrier itself was a challenge. Aircraft carriers are enormous! They can be the equivalent of up to twenty stories tall. Everything you bring onto them has to be hand carried up many flights of very steep narrow stairs called ladders. Carts can’t be rolled through their hallways because there are multiple watertight doors that constantly have to be stepped over. All the walls, floors, and ceilings are made of metal, which does not make for a great environment for radio reception. Additionally, there is a ton of onboard Navy equipment that is transmitting a lot of RF. Naturally, on an active ship, anything that’s transmitting cannot be turned off. Somehow we were always able to find enough clear radio frequencies to get the job done; it took a lot of scanning to make that happen.

My main cart for Top Gun: Maverick was several stacked SKB cases. The larger top case contained a Zaxcom Mix 12, a Deva 16, two Lectrosonics Venues, a Meon power supply along with Comtek and Lectro IFB transmitters. This section held essentially everything needed to record all of the dialog on the carrier. The top section is relatively easy for two people to carry wherever it is needed. By adding a PSC Pelican lithium battery to the onboard Meon, it had all-day power.

When the carrier was docked, I did all the scenes. When the carrier went to sea for a few days, I reached out to Eric Ballew, who had been my go-to consultant for carrier research. Eric is a Sound Mixer, who, while enlisted in the Navy, had been deployed on a carrier. Being “deployed” was very familiar territory for him. He did a great job on the work at sea. Thank you, Eric.

In addition to all the inflight recordings and the work on the carrier, there was one other big sound challenge; a sailboat scene that was not boom-able and had to be lav mics only. This scene was filmed multiple times, in multiple locations. The big issue was that there would be a lot of wind on the lavs. This is one of the places where I’ve found that DPA lavs really shine. To me, the DPA’s seem to be the most wind resistant of all the lavs I’ve ever tried. Each time, I would set up down below with a Deva big rig and a couple of 411’s.

Below deck on a boat is where those who get seasick, really get seasick. For some reason, I am not afflicted. On Dunkirk, I spent forty-plus days below deck on the Moonstone, a small wooden boat that would pitch like crazy in heavy seas. It was not a boat that was really meant to sail on the ocean. For some reason, while almost everyone else was incredibly seasick, I found I was impervious. I never even took Dramamine. I don’t know why, but evidently I am immune to sea sickness.

Each time we shot the Top Gun: Maverick sailboat scene, we wired the actors up with SM’s and DPA 4071’s. The lavs worked and sounded great, despite the high winds on the water. The DPA’s always worked.

Most of Top Gun: Maverick was shot at several naval air stations that we returned to multiple times. Each location had its own set of particulars that we had to figure out. At one base, this block of frequencies didn’t work, at another, a different block of frequencies didn’t, or there was a big humming noise in the corner that we couldn’t turn off in that hangar.

Top Gun: Maverick ended up filming for more than a year of principal photography, during which many old friends came and went, and all of us who went the distance had the opportunity to really bond with each other. With all the problem solving that each department had to do, we all did our best to help each other figure out how best to get the job done. Everyone on the main crew was extremely supportive of each other. It really was an extremely collaborative undertaking.

For me, it certainly was a learning experience, both technically and philosophically. I came away from the experience with nothing but respect and admiration for every service member I met. From the pilots and mechanics who helped guide me to the PR Department that showed me the path to connect to the plane’s Comms, to the members of the Navy brass that I later spent time with. Everyone was kind and thoughtful and extremely helpful. On more than one occasion, I had an Admiral sitting next to me at the sound cart for most of the day. They were thoughtful, caring, well-educated people, whose main objective was to do whatever they could to act in a way that would always minimize casualties for those whom they commanded. None of them took that responsibility lightly. I was very impressed.

Summing up, Top Gun: Maverick was a very challenging shoot for all departments. Everyone, cast and crew, worked extremely well together. We all did our best to support each other, and to problem solve all of the unusual situations we were given. I’m proud to say that every line of the inflight dialog in the movie is from the production tracks. Even the labored breathing you hear from Tom Cruise in the trailer is production track. Everyone who worked on this film went above and beyond, and it shows. In the end, I think Top Gun: Maverick turned out to be a pretty darned good movie.

Now, grab some earplugs and go see it on a big screen in an actual movie theater, with a nice loud Atmos surround sound system!

Over and out, Mark Weingarten.