by Steve Nelson, CAS

I had some idea what to expect when I heard that the pilot we shot last spring for DreamWorks Television had been picked up by ABC. The one-hour pilot episode of The River was shot in Puerto Rico (PR) and, while it was no surprise that the new episodes would shoot in Hawaii, it was a little disturbing that we were nowhere to be found in the fall schedule. Eventually, the other shoe dropped and it was revealed that we would be a midseason replacement with a seven-episode order.

THE STORY

Dr. Emmet Cole (Bruce Greenwood), famous television explorer and family man watched and loved by millions—think Steve Irwin crossed with Jacques Cousteau, dosed on acid, “There’s magic out there!” his tag line—has gone missing along with his crew, presumed dead somewhere up a mysterious and increasingly bizarre Amazon tributary. When his locator beacon is suddenly detected, a search is mounted, spearheaded by his wife and son (Leslie Hope and Joe Anderson) and their producer (Paul Blackthorne) with the twist that it is to be filmed for broadcast. The show was co-created by Oren Peli of Paranormal Activity fame and master of the “found footage” concept. His concept was to make a show that, while strongly written and acted, would have the look and feel of a documentary, but in the supernatural thriller genre. Scary stories of ghosts and magic shot like unscripted reality TV. On a river, in a boat, in the jungle.

THE CHALLENGE

What does this mean for the Sound Department? The first thing we learned before we even left for Puerto Rico was that it meant shooting with many cameras. Up to 14, in fact, and almost every type of HD camera: a couple of Alexas, the hero cameras, Sony EX-3s for the on-camera/actor cameramen, a consumer handicam and Canon 5D and 7D for mounting and random hand-held, and GoPros anywhere you could hide them. (That’s right: We’re shooting broadcast-quality video for a prime-time network show with the same $200 camera you buy to strap onto your board, your bike helmet, your skateboard, your dog. Welcome to our brave new world!) Not to mention the camera mounted on the miniature radio-controlled helicopter, the so-called Laser Beak. Besides the actual camera operators, whether cast and/or crew, Dr. Cole’s boat, the Magus, is wired for video, with a switching/edit room amidships. There are cameras and apparently microphones everywhere imaginable, including a few places not so imaginable. With so many cameras running, we captured so much, let’s call it visual data, that the problems I had sneaking in a plant mike surely paled in comparison with the work the editors had to do just to get through dailies. The visual equivalent of recording all eight tracks all the time. Oh wait; I did that!

With shooting underway in San Juan, I learned from Oren Peli, our co-creator and executive producer, that, in his world of “found footage” movies (The Blair Witch Project, Cloverfield, Paranormal Activity), the only microphone needed was right there on the camera, so why was I even there? We had several half-joking conversations about this, and I think I was able to persuade him that despite our flagrant deviation from his strict philosophy and aesthetic of this relatively new genre, I was bringing something better than that camera mike and that the studio and the network would be much happier this way. The company had already spent quite a lot getting both me and Knox White, my excellent and endlessly entertaining boom operator, plus several pallets of sound equipment, to this island location. I reckoned we weren’t in imminent danger of replacement by that camera mike.

SO MANY CAMERAS

SO LITTLE TIME

Next we learned that with up to 14 cameras working, there really isn’t any place for a boom operator, much less an actual overhead microphone. Most often all we could get with the boom were the slates. Fourteen cameras means 14 IDs and markers. (Including the GoPros, which, at 25 fps only, were not technically sync cameras since everything else was at 23.978 fps.) Sometimes the best entertainment was watching the slating unfold. When I told the camera assistant that he had to voice ID each camera, his job got a lot harder, remembering each camera in its sometimes obscure location and rattling off each ID in a charming Puerto Rican accent. By the end of the season in Hawaii, the guys were so fast that I even had to slow them down a bit so the poor dailies folks could sort it out. If the cameras were too spread out over the boat for Knox, I might have to sacrifice a radio channel or two just for slates.

In this new hybrid world of fake-umentary (scripted posing as reality, the better to scare you), we would have actors who would play the camera operators and be prominently featured. In subsequent passes, we would float in one actual camera operator and then the other to get the shots we actually wanted. If one of the actual operators got into another’s shot, it was accepted that he would be cut out. As it was acceptable to reveal the cinematic process by showing the cameras, the question of sound naturally arose. There was no sound person in the script I read, but for about a minute we entertained the idea that it would be OK to see the lavalier mikes as part of the documentary process. This concept didn’t make it to Puerto Rico before the myth of the on-camera microphone prevailed. Business as usual: hide the lavs, forget about how quality sound is actually recorded, even in our make-believe world. Cameras and cameramen are apparently sexy enough for network television, not so much sound guys and their gear. (Personally, I think it all changed when we put away our quarter-inch machines; Nagras were hot! John Travolta didn’t have a digital recorder in Blow Out; there’s just something about those spinning reels.)

Our fate was becoming clear: The River would be a wireless show pretty much all the way. Wire everybody always unless they were going in the water. Forget about sneaking in the boom for the close-ups or even hiding a mike; it just didn’t work like that. This wasn’t “tight and wide;” this was tight and tight and wide and wider and tight and one up on the rigging and so on until we ran out of cameras. At this point, all I could do was embrace it. Forget about mixing for perspective; that is so last century! If their lips are moving, put them on an iso track, make sure the fader is open, record the words on the pages and be ready for more. Even if you could see all the monitors, who has time to watch? Just mix, baby!

ONE IF BY LAND, TWO IF BY SEA

My work would be divided into two categories: Land-based, which meant I could work from the comfort of my cart with all 14 channels of wireless and the big Yamaha board, and waterbased, which called for a much more portable setup. Land-based mode would work if we were on the boats, dockside. Our first two days of shooting were interiors on docked tugboats, which, being built entirely of steel, require special consideration for radio work. We also built sets for some of the boat interiors. The scenes in Zodiac boats zipping through the mangroves or on our practical boats underway or traipsing through some inaccessible jungle, obviously called for a portable, studio-in-a-bag modality.

THERE WILL BE TRAVEL

The story unfolds in two parts: the pilot in Puerto Rico and the seven episodes shot on Oahu. Pilots are always a bit special and often quite memorable. This one was. Although PR has been a location in many movies and television, this was the first time for many of us. We were gifted with the participation of Luis “Peco” Landrau, our utility person. Peco (“Freckles,” he’s a rare Puerto Rican redhead) is an experienced mixer and boom operator who mostly does utility and second units for visiting productions. His uncle is a highly respected mixer there and taught him well; he is extremely professional, prepared for anything, speaks English and gets along with everybody. We were fortunate to be working with DP John Leonetti, who I’ve known for many years, very talented and a real gentleman. John brought enough of his people to feel comfortable and the locals who rounded out our company were very experienced and competent. Of course, when it’s not too busy in a place like this, the top crew is available and we had them. Our production staff was strong, led by line producer Bob Simon, local unit manager Ellen Gordon, and first AD Dan Shaw.

Our director, Jaume Collet-Serra, a Catalan of no fixed address, known for films likeOrphan and Unknown, was embarking on his first adventure in directing for television. The pilot sets the look and the tone of the series and Jaume really went for it, creating a multi-faceted, jittery, sweeping pace that never let up in its intensity. He loves to grab a camera and operate and was fearless, while still showing concern for the quality of our sound and the intelligibility of the dialog. The profusion of accents among our cast was of some concern. We had U.S., Canadian, three different flavors of British (including one doing American), German, Mexican (her character doesn’t actually speak English), and an American doing an unspecified South American accent. We discovered in post that there is no sound problem that can’t be fixed with subtitles. With The River’s “documentary” feel and its use of chyrons for dates and locations and characters, this technique worked very well both for translation and getting us through a few rough spots. I want subtitles on all my shows!

A word here about our lovely cast. This was a truly international ensemble and a more generous, spirited, cooperative, talented, friendly and respectful group could not be found. They all seemed to understand that if this endeavor were to be successful, all the parts would have to work, including sound. Under the circumstances, with so much wiring going on and so much action, this was key. No complaints, endless patience and a costume designer who really got it; the wardrobe was very forgiving and easy to work with.

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

It had been a long time since I’d had to do extensive over-the-shoulder work. Back in the (very) old days at Entertainment Tonightwith a BVU 110 over the shoulder, a couple of lavs and a short stick, tethered to a running cameraman chasing stars down the red carpet. Or doing docs with a Nagra, hoping that the take-up reel hadn’t jammed leaving me with a massive pile of spaghetti under the lid. Since the breakout of reality TV and the digitization and further miniaturization of our gear, bag

work has made major strides. How then to gear up for maximum flexibility, ease of use under challenging conditions, best use of equipment I already own, and cost efficiency? The goal was to have two separate recording packages so that I could quickly transition from one to the other. Since I have 14 channels of Lectrosonics UHF wireless spread across four frequency blocks, it was an easy choice to stay with Lectro, enabling me to use a subset of my transmitters in all situations. But what about receivers? The Octo-Pak is very desirable but perhaps a bit over budget for a pilot; for this gig it would be the Venue Field, giving me six tunable receivers in a single box. Of course, if there were more than six speaking parts in a scene, choices would be made; no matter how many wireless you have, sooner or later that will happen. A little research told me which blocks would give us the least interference (almost anything is good where we were going). I would install the appropriate modules and be ready to make a seamless transition from cart to bag mode. (One note about the Venue Field: about the only thing that can go wrong with this all-but-bulletproof device is that there is a chance of damaging the battery contact, a flimsy metal tab. Not a big deal, but it is a good idea to have a spare in the kit.) An eight-track, fully featured recorder/mixer would be required; for the pilot I tried a Sound Devices 788T with a CL-8 controller. As a longtime Deva user, it took a little getting used to the different interface. It is a brilliant unit and, once I gained confidence that I could work it in a pressure situation, the Deva 5.8 stayed on the cart. Since I was using the Venue, I had not the forest of antennas resulting from a bag full of receivers, but antennas are still required. On the pilot I used two log periodic sharkfins, mounted on plastic rods which got me good range. I also picked up a Comtek M-216 Option 7 transmitter so that all Comteks would work from either setup. Shove it all into a Petrol bag and it is very easy to pick it up and go, potentially without changing actors’ wires or Comteks.

RUM DIARIES

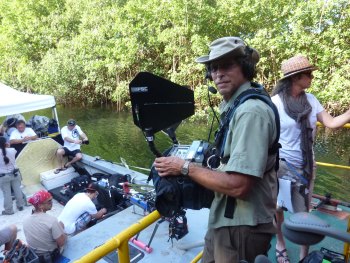

Yet another camera operator, Laser Beak. They could really thread a needle with this. Puerto Rico is far. From the West Coast anyway. First you fly somewhere far, say, D.C., then you fly quite a ways further. We were put up in the capital, San Juan, which gave us good access to our dry-land locations and wasn’t too far a drive to Rio Grande, near El Yunque rain forest, and our little river. A U.S. Territory, Puerto Rico is a spicy mix of Spanish, Caribbean, and U.S. American. Spanish is prevalent, of course, but English is also spoken and taught. The currency is familiar but distances are measured in kilometers. With its Spanish colonial heritage and architecture and tropical setting, you feel like you’re in another country but there are four Costcos on the island and many strip malls with all the familiar chains. It should be noted that the Costcos here carry an excellent selection of local rums, quite reasonably priced. As the city grew, parts of the infrastructure did not keep up; there is little in the way of reliable mass transport, everyone has a car, so traffic can be bad. It is painful to be stuck in the morning rush hour on your way home after working all night, but that is really not so different from anywhere and at least we were in a chauffeured van. There are many great restaurants in San Juan, just none close to our hotel. We were at the Hotel Caribbe, one of the original tourist destinations from the swingin’ Rat Pack ’50s, refurbished nicely, located a long walk from Old San Juan and a shorter walk from the newer strip where most of the hotels, casinos, and restaurants are and where film crews usually stay.

The small slice of Puerto Rico that we experienced on our days off during our three weeks there was lovely and entertaining. Tropical climate, nice beaches, diving, snorkeling, sightseeing, eating & drinking, music, clubs. Knox and I even managed to work in an excursion to the beautiful island of Vieques to see the amazing bioluminescent bay. (That only involved a drive to the marina on the east end, a boat to the island, a van ride to the nature center and dinner, a bus to the bay, an electric boat on the bay, then finally, a dip in the psychedelic water, and then the whole thing in reverse. But so worth it!)

Working there was great. There is decent infrastructure and good crew used to working with Hollywood productions. We had a cozy but well-outfitted truck to share with video assist and a very attentive owner/driver. We were lucky to have Peco, who had been working with all these people forever; it felt very much like family. Working in a tropical place, it is not a matter of if it’s going to rain, but when, and the locals certainly get that. The first thing off the truck is the easy-up, which is automatically sandbagged: rain protection always. If it’s not raining, the sun will scorch you, so you’re covered both ways. The question is why does it always seem to rain right at wrap? Since we were working near or on the water in a pretty wet area, mosquitoes were plentiful, but nothing that a healthy dose of DEET wouldn’t solve. (Sorry, but I’ve learned that none of those alternative repellants, from Avon Skin So Soft to whatever natural product, are at all effective.) However, even after slathering on the DEET for our frequent night work—scary things do happen at night—I found myself terribly bitten. I thought I had bed bugs, which was ruled out after the hotel tore apart my room in search of them. It turns out they have some particularly nasty no-see-ums, biting midges. The best solution I found was long pants and long sleeves at night.

There is no soundstage in Puerto Rico outside of a television station. Instead we built sets, boat interiors mostly, in a dank and airless warehouse. The best that can be said about this place is that it was right next to one of the aforementioned Costcos and wasn’t too far from the hotel.

Our river location was on the east side of the island, below El Junque rainforest, near the town of Río Grande, on the Río Espíritu Santos, about 45 minutes to an hour from our hotel. It’s not much of a river; at points you could throw a quarter across it, but it is quite navigable and gave us long runs in either direction with little spurs and mangrove choked banks. It feels isolated even though it is close to the road, a couple of villages, and apparently an airfield. It is lush and green without the constant rain and restrictions of shooting in the actual jungle, but the wide shots would require some digital set extension and augmentation to really sell the Amazon. The boat playing the Magus was a full-sized, 60-foot working vessel not designed for this kind of environment. The art department did a great job of dressing it way down to give it a profoundly abandoned look, but it was very challenging to get it over the sandbar at the river’s mouth. We were lucky to be there during a full moon that was actually closer to the Earth than usual, which created a higher than normal high tide and allowed us to make it upriver.

THINGS THAT GO BUMP IN THE NIGHT

Once we got underway, and once we got our heads around the concept of such a multiplicity of image capturing devices and their effect on our work, it was business as usual—almost. All departments share many common problems working on boats: cramped space, not really production-friendly. Kind of like a big insert car on water, it is hard to make changes once you’re moving, much less stop or return for something you need. One issue that particularly concerns the sound department: what motivates the boat? Since we were using practical boats, there was the self-powered option. However, the few times that we fired up the twin diesels on the Magus, they were so loud that it was difficult to think, much less record dialog. Fortunately, we had Dan Malone heading our marine department. Dan is a guy who makes you both feel safe in all situations and that he understands your needs. He provided a large skiff which was used as a working platform and to push or pull the Magus and the smaller S.S. Hopewell—the boat that takes our intrepid travelers to find the abandoned Magus. Its engines were powerful enough to do the job, yet quiet enough, and the skiff long enough, to keep them at a respectful distance. The conceit was that the relatively quiet motor noise could be justified and blended with actual motor noise in the final mix. As these were working boats, we could have a pilot in the wheelhouse actually steering; this was not the case in Hawaii as you will see.

If the boats were moving or parked offshore or if we had a rugged and distant jungle location, I needed to grab my studio in a bag, the appropriate transmitters and mikes and go mobile. Knox would join me to manage the wiring and get the slates and maybe even boom a shot. Onboard, it could be challenging just to stay out of shot—did I mention that there were lots of cameras and never a tripod? I could often find a safe perch on the upper deck, which gave me a nice view of the surroundings, if not the action, and lots of fresh air. Sometimes the ferrous construction would limit my radio range; we might remote the antennas or I might have to scamper down from my crow’s nest to get closer. We did have a video assist operator who was responsible for wrangling the many monitors attached to the many cameras, but once on board, he had his problems too. If it was feasible to set myself in view of the monitors, I would take advantage, but usually they were crammed in a corner with too many people so it seemed best to find a relatively comfortable spot, keep my eyes on the script, and imagine what it would look like. This worked well; it kind of took me back to the very old, pre-video assist days.

When the boats were tied up to shore, it was possible to work from the cart. I could park in a comfortable spot and push my RF cart close to the water’s edge. I keep all the radio equipment, receivers and transmitters (Comtek and IFB) on this cart, which is tethered to my mixer’s cart by means of an Aviom digital snake. This allows me 16 channels in both directions via a piece of Cat-5 network cable up to 300 feet long. (I’ve gone even longer than that with no ill effects.) Of course, this adds another cart to the package, but I find the increase in flexibility more than worth it. Rather than remote all those antennas, we move the whole package—antennas, receivers, transmitters, power—drop anchor, connect the Cat-5 and you’re good to go. Aviom makes a good product, born of rock and roll, surprisingly sturdy and very transparent.

We had a few days when we were working with the inflatable Zodiac boats. Four boats, two with actors, an actor cameraman or an actual camera operator on each, simultaneously shooting as we zipped down our little river through the mangroves to where we emerge to find the Magus. We were in a follow boat trying to stay out of shot and yet within range of the video transmitters and my audio transmitters. Those Zodiacs are loud and the very dense mangroves and the water really do soak up the RF. This would have been a good opportunity for the Zaxcom TRX series of recording transmitters. When things get stretched beyond the limits of RF transmission, there is always the option of putting the studio in a bag in the boat with the camera and the talent, pushing “record” and sending them on their way. Sometimes that is the best choice; mostly we were able to keep our link by virtue of good driving. Reminding the actors to speak above the motor noise also helped. The situation is made more complicated when the actors are not only piloting the boats but operating the cameras, but with the coverage shot by the real camera operators and our persistence, we got the scenes.

As night falls on the river, along with the bugs there is a rising chorus, an onslaught of sound, quite formidable and immediately recognizable once you’ve heard it. It is los coquís (onomatopoeically: accent second syllable, rising pitch), the little frogs, the unofficial mascot of Puerto Rico, out looking for love every night. Barely an inch long, they raise quite a racket and there is no controlling them. I went to some trouble to get some nice clean coquí tracks, heading out on a small boat away from our encampment with a small Olympus pocket recorder. It was surprising how noisy it was out there when all you’re recording is frog wallah. It is a distinctive sound, quite lovely and, for Puerto Ricans, very nostalgic, and it is all over the soundtrack of the pilot. I had thought this unique sound would be used throughout the series for continuity’s sake, but it was left in the Caribbean. Although coquís had been introduced to Hawaii back in the ’80s, they were considered an invasive pest (along with almost every other animal and plant on the islands) and eradication programs were undertaken. I never heard one over there.

The water work fell into the middle of our schedule; once we finished out in the wild, we fell back to our stage work for a few days and then finished with one of our few days shot on location in the city. Then pack it up, ship it home and adíos. A final word of caution regarding departure from Puerto Rico: My equipment had been air freighted out of Los Angeles by a reputable firm and had arrived intact at our stages in San Juan. If you find yourself working down there, do not assume that your outgoing shipment will be treated with the same respectful diligence. Absolutely be sure to supervise any packing for the return trip.

WE’LL BE RIGHT BACK AFTER THIS BREAK

To be continued in “Up The River in Hawaii.” What? There are no actual rivers in Hawaii? Good point but we didn’t let that stop us. Learn how in the next issue.