Occupied Land

Production sound joins an ensemble effort to realize Director Taylor Sherdian’s cinematic story Yellowstone.

by Daron James

Thomas Curley CAS casually takes a sip of his iced tea while sitting outside a North Hollywood pizzeria. The sun settles behind a scattering of puffy grayish clouds as a breeze wisps by reminding him of the weather conditions sound endured while recording Yellowstone, a 10-episode scripted series from creator Taylor Sheridan, whose written material includes Sicario, Hell or High Water and Wind River, the latter which he also directed.

Curley’s relaxed, approachable demander disguises any of his previous accolades—a career that started out shadowing Sound Mixer David MacMillan, a now CAS Career Achievement Award recipient and Boom Operator Duke Marsh—which has flourished into an Academy Award, AMPS and BAFTA win for his work on the Damien Chazelle-directed Whiplash. The New York native is as humble as they come residing in Los Angeles and building up the appropriately named location sound recording company Curley Sound with his brother Brian Curley.

“This was the biggest show in terms of scale I’ve ever worked on,” says the production sound mixer, who was hired on through a Whiplash connection via First Assistant Director Nick Harvard. With its massive scope, Yellowstone was an “enormous undertaking” in terms of its production. The hour-long series was the first greenlit project from the newly formed Paramount Network, which meant “quality was the top priority.”

The allegory follows the Dutton family, led by John Dutton (Kevin Costner), who controls the largest ranch in the U.S. and the people that are trying to take it away from them by any means necessary. Accompanying Costner is Wes Bentley, Kelly Reilly, Luke Grimes and Cole Hauser, who plays his sons and daughters, as well as Gil Birmingham, a local Indian Chief named Thomas Rainwater and Danny Huston as a greedy land developer.

Production shot in parts of Utah and Montana from August to December of last year utilizing the Utah Film Studios in Park City for its studio work. For crew, Curley tapped veteran Boom Operator Knox White and local Utility Andrew Cier. “Production’s hands were tied in terms of spending extra money to bring out a third, but it turned out very well. Andrew came up working with some good people like Sound Mixer Jonathon Stein (The Sandlot). Plus, he knew the local people, the area and the terrain.” Working with White on the other hand was something that was always in the back of Curley’s mind. “I did a day or two with him a while ago, but for most of my career, he was three tiers above me doing James Cameron films. Our stars finally aligned and I brought him out into the woods. He’s a surgeon with the microphone and very endearing,” says Curley. “Better yet, he has stories for days which made the tough days a bit easier.”

Curley was flown out for a week before production and engaged with Cinematographer Ben Richardson (Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Chi) to find out “how tough he was going to make it” for them, he jokingly says. “In terms of DPs, Ben really knows technology which is near and dear to myself. He made a really good recommendation that turned out to be the best money I think I have ever spent.” The suggestion was the Ambient ACN Lockit system for timecode. Curley implemented Ambient Nano Lockit boxes to three ARRI Alexa cameras and one Alexa Mini with the Ambient Master Lockit. “Routing our timecode this way proved it was something I never had to worry about and it also made camera happy.”

A production meeting ironed out basic concerns, and for sound, they found out for most part they would be out in the middle of nowhere. Even indoors or inside a house, they would be out in the middle of nowhere. The only big metropolitan stops being locations in Salt Lake City and the small town of Darby, Montana.

Shooting style dictated its own set of challenges as Sheridan directed all the episodes and blocked organically moving through 7-8 pages a day using a three-camera setup. A fourth camera, the Alexa Mini, was stationed on a jib and massaged into the workflow as well. Outdoor sets, which included different areas of the Dutton Ranch, covered hundreds of yards in any direction. Sound had to be ready to cover anything from groups of actors riding on horses often coming from two different directions to following groups of actors traveling uphill, down through valleys and across rivers. Vehicles intermingled with horses, people intermingled with herds of cattle, bison and the occasional grizzly bear.

Authenticity was important to the director in order to ground the story and the characters in it. What this meant for crewmembers was turning the whole world around to prepare for the next shot. “Our sets were massive pieces of land so every time we needed to move, we’d often have to push things one hundred yards in another direction over a rocky, hole-filled terrain,” Curley says. Trucks, equipment, crew, video village—everything had to be transported and positioned out of frame. “No one ever felt rushed because everyone was in the same situation. The ADs did a wonderful job handling the logistics to keep the train moving.”

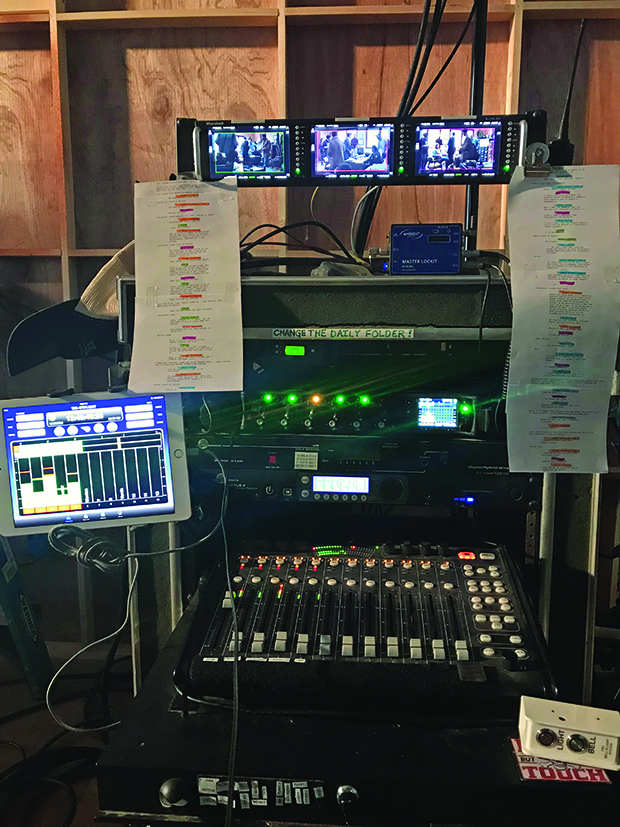

Sound and other departments used Gator utility vehicles for mobility and Curley constructed two sound carts for different types of shooting. His main cart consisted of a Sound Devices 688 and CL-12 linear fader controller with a Lectrosonics Venue 2 (wideband low) and the original Venue (wideband low) to handle larger scenes. Then a PSC Euro Cart dubbed the “Pony Cart” touted a Sound Devices 633 and a PSC RF Multi SR Six Pack with Lectrosonics SRb Dual Receivers. The smaller cart transitioned easily into bag work. A Comtek base station handled the video village feed and Lectrosonics IFB for boom and utility.

For most of the exterior locations, Costner’s character and the men who worked for him wore thick flannel-styled shirts paired with a large jacket similar to the Carhartt brand and jeans. Sound worked with costumes in pre-production to find a “happy spot” to hide the lav, then gum was placed on the zipper to keep it from slapping around while on horseback. Curley admits he likes to produce “high-quality sound recordings” with a “certain consistency” which meant using the same microphones for the entire run of the project. Sanken COS-11Ds were paired with Lectrosonics SMQV and SMQ transmitters and the occasional Countryman B6 was implemented when a lav needed to be placed outside the wardrobe or when water was in play. Schoeps CMIT-5U, CMC4/MK 41 and Sennheiser MKH 60 and MKH 50 microphones combined for the overhead work. Wireless booms were equipped with a Sound Devices MM1 preamp for easy access to gain control.

The pilot episode opens up with a car accident where John Dutton is left bloody trying to find his bearings as horses scatter. It’s a visual metaphor for the clash between the country life and the impending urban development that overshadows the ranch. Horses a very much part of the narrative and sound was mindful of safety precautions. “It was all about communication,” admits Curley. “Knox was really good about making sure everyone was comfortable on set with any boom movements and tried to buddy up with the animals as much as possible.” Animal Coordinator Paul ‘Sled’ Reynolds, who worked on Dances with Wolves with Costner, ensured everyone’s well-being. Sound would swap out the boom for a lav if issues arouse, and other times, Reynolds would change out a horse if they were acting up to no fault of sound. “We tried to be cognizant of potential problems. If you are, you can try to get out ahead of it,” adds Curley.

The vast landscape created swirling windy conditions that were muffled with either a Rycote or Cinela windscreen. At peak wind, lavs needed to be buried under wardrobe with fur. Curley felt the brunt of the conditions during the practical car work when he and a focus puller would hide in the bed of a pickup truck as it zipped through the countryside. The car setup included all the common rigging and lighting, and to record audio, Curley tapped the bag version of his Pony Cart and placed a Sanken CUB-01 boundary mic above the visor and wired the actors. Besides traditional drive-and-talks, cops would pull over vehicles or multiple cop cars would swarm in. In the latter case, additional wires were needed and the boom would join in to pick up sound. “There was a lot of adapting as we went along,” explains Curley. “They eventually changed the driving shots to green screen for more control because many of the roads were extremely bumpy and shook the frame.”

Luckily, it wasn’t all exterior location work as the sound team found itself inside the Helena, Montana, Capitol Building for a scene where Jamie Dutton (Wes Bentley), a lawyer, tries to defend the family position. The sequence had Jamie speaking at a lectern in front of the governor and other officials. To cover its sound, booms were played overhead and the podium microphones in front of them were turned on and recorded to a separate track as an option for post. Additionally, Curley turned off the PA system inside the chamber so it would not interfere with the lavs or boom mics.

One of the larger interior scenes of the pilot took place at a cattle auction. As John enters the building, the camera tracks him around the auction area where hundreds of extras sit and on up to a second floor VIP room. He grabs a seat and watches a little girl sing the National Anthem as others approach him with their own concerns. The scene was filmed at an actual cattle auction location in Utah and Curley brought in a live audio person to set up the PA speaker system and stage mics. More than six hundred feet of XLR cable was run for the setup. Curley hid behind a door underneath the VIP room and was able to mix in the National Anthem, crowd and cattle noises into his mono track, along with the natural reverb of the auction. Upstairs, multiple lavs and a boom recorded the dialog between the characters.

Mixing, Curley prefers to run a limiter “just in case,” as with digital, “the only thing that can’t seem to be fixed is overmodulation.” “Running the limiter makes me aware of my gain structure. If I find myself hitting the limiter more often than I should, I turn the gain down. It keeps me honest,” says Curley. He also tends to not play with parametric EQ basing, his philosophy on the idea that it’s better applied in a controlled environment where it can be easily removed if it doesn’t work. A low-frequency roll-off around 80 Hz or as much as 120 Hz is added to the mix if something noisy is nearby like in many of the scenes that feature a helicopter.

John Dutton uses a helicopter as a mode of transportation around the ranch. Dialog driven scenes took place either directly outside before boarding or through headsets during flight. To record usable audio, the team employed two methods: one with the helicopter turned off completely and the other with the engine turned off but the rotor still churning.

Wide and tights are the norm for most productions, but the sound team faced super-wide shots to show the striking landscape coupled with extremely close shots that followed the action. “We were getting the audio, not the way we’d like to, but something I learned over the years is that you address your concerns and ultimately you have to let them decide.” To curb larger audio issues, the wide camera would be turned off once they achieved what they wanted visually.

Curley pushed the gear to its limits, often running 10 ISO tracks with some scenes featuring eight different speaking parts. Double booming was the norm and actors were wired the majority of the time with the exception of some stunt and action sequences. The mixer arrange his wires in dialog order so he could visually see the progression of the scene on his faders. “It’s easier not to get confused this way instead of going back-and-forth across the board. If I haven’t brought up a fader, I know the dialog will still be coming.”

In a climactic scene of the pilot, sixteen men were on horseback, others rode four-wheelers, police cars lined the road, gun shots were fired and a helicopter flew overhead witnessing the chaos. The scene was shot over three nights and broken up between action and dialog. While it was one of the biggest track days in terms of wired actors for sound, the way it was scheduled allowed them to keep pace. “Logistically, there was a lot of moving parts, but it was just a matter of jumping in and keeping our high standards,” says Curley.

Realism was a theme throughout the production. Whether it was importing trees from Montana to build the log cabins inside the studios or the fight scenes where stunt men didn’t hold back or the extensive aerial coverage that enhanced the scale and scope of the story. Eight episodes were shot before weather curbed production. The final two will be finished this year. “Quality is important to Taylor as a filmmaker,” says Curley. “If you watch his other projects, he is very intent on making a real and believable world for his characters to be in. That decision to be authentic doesn’t make our jobs easier, but that’s not why we are there to do it. We’re here to support him and I really lucked out having Knox and Andrew with me. When you start seeing episodes on screen, you get a feeling that all the hard work you’ve done is worth it.”