by James Delhauer

When looking at the history of the technology that defines our industry, the acceleration of progress that has occurred in the recent past is truly staggering. In 1953, the National Television System Committee (NTSC) introduced the color television broadcasting format, which is colloquially known today as NTSC Standard Definition. Though minor variations on the format were introduced over time, it remained mostly unchanged until the first high-definition television standards were officially adopted in the United States more than forty years later in 1994. But just twenty years after that, in 2014, that resolution was made obsolete when the first digital streaming services began to widely distribute content in a 4K Ultra-High Definition (UHD) television resolution. Though 4K UHD is the current highest standard of content distribution, current speculation suggests that mainstream adoption of even larger 8K displays will begin in the United States in 2023 and that distribution platforms will start officially supporting it shortly thereafter. If accurate, this would mean that the amount of time between home media standards has halved between each leap forward. And in the not-so-distant future, that could be a very real challenge.

A digital image is made up of what we call pixels—tiny dots that come together in rows and columns to make up a single image. What we call resolution is a measurement of the number of pixels in a given image. NTSC Standard Definition format images are made up of six hundred and forty vertical lines and four hundred and eighty horizontal lines, commonly represented as 640×480. Though a variety of different high-definition formats do exist, the one referred to as True HD increased those figures to one thousand, nine hundred and twenty vertical lines by one thousand and eighty horizontal lines. This is referred to as 1920×1080 or simply 1080 for short. This increase in pixels results in substantially more dots being used to make up the same picture, allowing for more detail, precision, and color shading when replicating what a camera’s sensor captures, making for a more nuanced product.

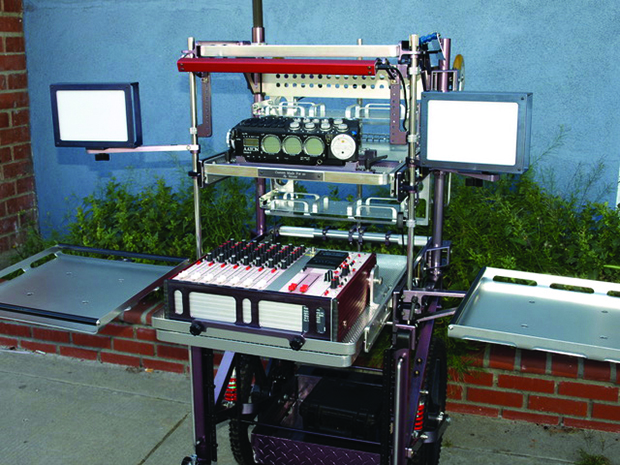

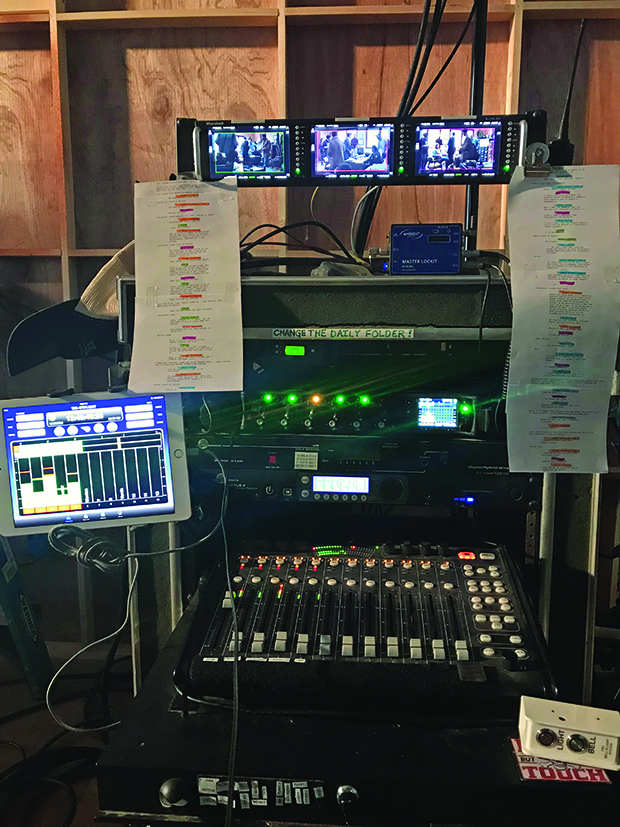

But while we all love to be dazzled by the absolute clarity, color, and sharpness that high-resolution imagery can offer, there are very real logistical quandaries that filmmakers need to consider. For Local 695 data engineers in particular, whose responsibilities can include media playback, on-set chroma keying, off-camera recording, copying files from camera media to external storage devices, backup and redundancy creation, transcoding, and syncing, digital real estate is a growing concern. At four times the number of pixels as Full High Definition, 4K UHD means four times the amount of data is captured over the same amount of time. The impending move to 8K will multiply this amount by another factor of four, as 8K is double the number of both horizontal and vertical lines of 4K and not just double the number of pixels. In practical terms, productions will need to spend sixteen times as much money on media.

But drive space isn’t the only issue. Just because our data quantities are increasing does not mean that the films and series we make can accommodate turnaround times that are four and sixteen times longer. Therefore, we need faster drives and more powerful computers.

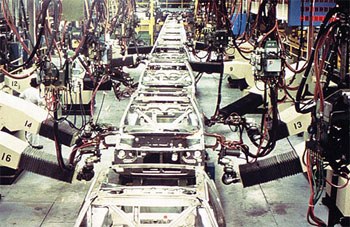

In simplest terms, a hard drive’s read and write speeds determine how quickly it can access the data stored within and add new data onto itself. For data engineers, this is of critical importance when transferring media from one location, such as a camera card, to another, such as a production shuttle. A standard spinning disk hard drive’s speed is determined based on how fast the disk inside of it spins. Typical work drives spin approximately seventy-two hundred times per minute when brand new. In theoretical terms, these drives are capable of transferring between eighty and one hundred and sixty megabytes of data per second. Unfortunately, even at this speed, these drives are not always suited for high-definition work—let alone the more intensive labors of 4K and beyond. A convenient way to get around the problem is through a process known as Redundant Array of Independent Disks, or RAID. Though RAIDing can be done in a variety of ways, the basic concept is that multiple drives are used to accomplish a single task. By using two hard drives (or more) instead of one, the task being performed can use the performance speed of each drive simultaneously. In live broadcast environments, it is common to use RAID configurations that are making use of anywhere from four to sixteen hard drives at once in order to ingest multiple cameras’ worth of media simultaneously.

However, while those speeds are impressive and more up to the challenge of high-resolution production, they do come with serious drawbacks. Every hard drive introduced into the configuration represents a potential point of failure in the RAID array. In a simple RAID configuration, the loss of a single hard drive could mean the loss of all footage contained within the array. More complex configurations take this into account and create redundancies but these require additional hard drives, returning us to the issue of real estate. Newer solid state hard drives—media devices that have no moving parts and therefore, don’t rely on disk speed—may represent a possible solution to the RAID issue in time. Though they are currently significantly more expensive (a single terabyte 7200rpm hard disk drive can be bought for as little as $44, whereas a solid state drive of the same size and brand will run you $230), they are significantly faster at performing the same tasks. This theoretically means that fewer drives could go into a single RAID configuration, reducing the points of failure in the array. Moreover, with no mechanical parts to jam or degrade over time, they may be less prone to failure in the first place. Unfortunately, we will need to wait for production costs to bring retail prices on solid state media down before this becomes a viable alternative.

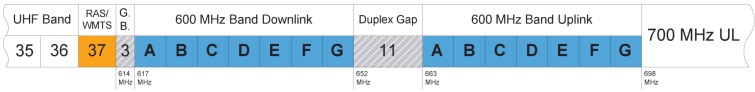

This is all assuming that a hard drive is not limited in any way by its connection speed to the computer with which it is communicating. The physical port that a hard drive uses to interface with a computer may have a speed limitation completely unrelated to the drive’s. The most common type of port, USB 3.0, has a theoretical limit of five gigabits per second, with one gigabit equaling approximately one-eighth of the more commonly measured gigabyte. A single spinning disk drive does not read or write faster than that and so there is no problem.

However, an array of drives working together can easily exceed that limit, at which point, data is going through a choke point when passing through the wire connecting a computer to a hard drive. At the time of writing this article, the fastest connection port on the market is tied between Thunderbolt 3 and 40g Ethernet. These two port types both have theoretical maximums of 40gbps, though neither has seen widespread adoption within the industry at this time.

All of that being said, engineers don’t just need to be able to move data around faster if we are to keep up with the demands of higher resolution. It is of equal importance that we process it more quickly too. Since working with ultra-high definition and larger formats requires a prohibitive amount of computer processing power, our editor friends in Local 700 rarely do it. Instead, they make use of a process known as “Offline to Online Editing,” where they use lower resolution proxy file copies of the camera media when assembling their projects and then swap out those proxies for the original high-resolution camera media when preparing to color grade and deliver. Where do those proxy files come from?

Us.

Local 695 data engineers can be tasked with creating these proxies on set, which necessitates being able to work with the raw, high-quality footage captured by the camera. This means more powerful and efficient computers are becoming necessary. There are several factors that determine how powerful a computer is for our purposes. Processor speed, memory, graphics memory, hard drive speed, and connection speed all need to be taken into account. For these reasons, and a few others, the majority of the industry has become reliant on Apple computers.

Unfortunately, Apple’s professional line of computers tend to stagnate for long periods of time. The Mac Pro, Apple’s line of professional grade editing machines, has remained unchanged since 2013. The company has announced a replacement, tentatively to be released in 2019 and a stopgap solution was introduced in 2017 when the company unveiled the iMac Pro but these computers are not cheap. An introductory iMac Pro costs $4999 while a fully upgraded machine can be bought for as much as $13,200. And this assumes the use of only one machine at a time.

While the world of major motion pictures has largely embraced the move from lower viewing resolutions to higher ones, with digital cinema cameras recording in 6K and 8K resolutions already, television has yet to catch up with the current Ultra-High Definition standards. In the United States, many series still record in high definition. It’s understandable when the sheer volume of footage is taken into consideration. While feature films record enough footage to assemble a presentation lasting between ninety minutes and three hours, television series spanning multiple seasons can last hundreds of episodes. The need to process and preserve all of that footage requires a staggering amount of resources. Doing all of that in 4K or 8K makes it an even more monumental challenge. But as the cost of 4K televisions, computer monitors, and even cellphone screens continue to plummet and as 8K displays are introduced into the market, our audience is going to demand that this challenge be met.

These concerns are not new. The jump from standard definition to high definition presented the same obstacles in the late 1990s. The new factor at play here is time. While we, as an industry, could no doubt rise to the growing needs of 4K production with time, the advent of the 8K world is already within eyesight. How far behind that is the realm of 16K? Another ten years? Or maybe just another five? It will be interesting to see at what point the innovation of one avenue of technology collides with the reality of another.