by James Delhauer

The evolution of communication technology since the turn of the century has revolutionized the way that filmmakers approach their craft. A short twenty years ago, productions made nightly phone calls and distributed paper call sheets each day to ensure that cast and crew were aware of the correct location and call time for each day’s work. Widespread access to personal email accounts rendered this manual process obsolete and saw it replaced with mass mailing lists and digital attachment files. This is just one example that scratches the surface of how sending files over the internet can make production workflows simpler and more efficient. As we move toward a more globalized world of film production, the ability to communicate via the web has become an integral part of day-to-day life. More and more assets can be shared instantaneously, saving countless hours or the cost of constantly transporting assets back-and-forth. The most recent developments in file transfer protocol technology are allowing for entire productions to be uploaded to the internet and sent to multiple destinations across the globe in real time.

A file transfer protocol, or FTP, is simply a network protocol used to transfer files between a computer client and a server. On a small scale, every email attachment makes use of an FTP in order to move the attached file from a device, onto an email provider’s server, and then send it to the recipient’s device. They have become a common, albeit nearly invisible part of the daily routine in production. More and more offices are adopting browser-based FTP services like Google Drive, Dropbox, and Amazon Cloud Storage in order to make sharing and communication channels uniform across the team. In cases such as these, the user need only enter the address of the FTP server into their web browser in order to access data that has been stored there by another member of the team. Username, password, and sharing credentials are often added as a measure of security.

Unfortunately, commonly known platforms such as these have their drawbacks. Most web browsers, such as Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Microsoft Edge, and Apple Safari are not optimized for large or automated transfer tasks. Similarly, most consumer computers are not outfitted for transfer speeds beyond one gigabit per second. Additionally, these sorts of services can also become quite costly as both the expense of cloud-based storage and slow upload speeds make the time commitment impractical. Moreover, FTP clients that utilize third-party servers present a security risk. If a production were to place all of its assets on a non-private server, those files would be vulnerable to theft should anyone obtain the correct login credentials. There is also the remote but still present threat that the server’s provider (Amazon, Google, etc.) may undergo some sort of catastrophe and data loss could occur.

Recent developments are removing these limiting factors and large-scale digital delivery is becoming more commonplace. Ten-gigabit internet connection pipelines have become more prevalent and cost-effective with time, which have in turn made ten-gig connectivity on consumer machines such as Apple’s Mac Mini and recently announced Mac Pro, far more common. This allows for larger amounts of data to be uploaded to the cloud and then sent to network servers. There are also more FTP workflows that involve using a specific client software, eliminating the inherent flaws of browser-based FTPs. Private servers and network-attached storage devices are more prevalent, meaning that production companies can build or purchase their own server solutions, which eliminates the vulnerabilities of third-party storage options.

Fortunately, these improvements are occurring at an ideal time within our industry.

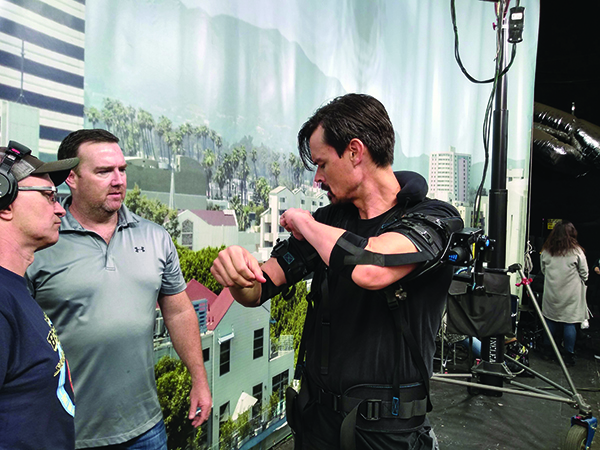

As productions have left the traditional filmmaking hubs of Los Angeles and New York in favor of exotic locations around the globe, production activities have become decentralized. Rich tax incentives offer unique opportunities that incentivize productions to shoot in new hubs that may not be where the footage is ultimately processed and undergoes post production. A project may shoot in Atlanta, undergo general editing in New York, and source out visual effects, color grading, and post-production sound to companies based anywhere else in the world. In complicated workflows such as these, every entity involved with the project needs access to the digital assets. Transporting physical drives can be costly and time-consuming. But simply uploading the entirety of the project’s assets to a server where any relevant parties can download the information is an ideal solution. This allows post-production teams to begin processing footage almost immediately, regardless of whether the shoot is occurring a few blocks away or on another continent. The expediency of this process also allows for near real-time feedback from the editors and dailies, which can eliminate the need for costly reshoots later in the production.

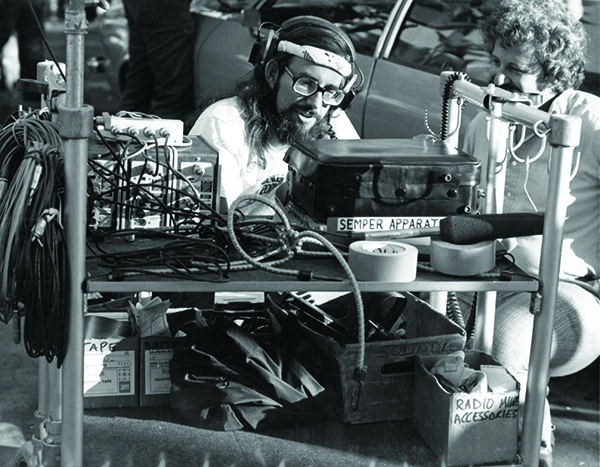

“For Local 695 video engineers…

this emerging technology presents an opportunity.”

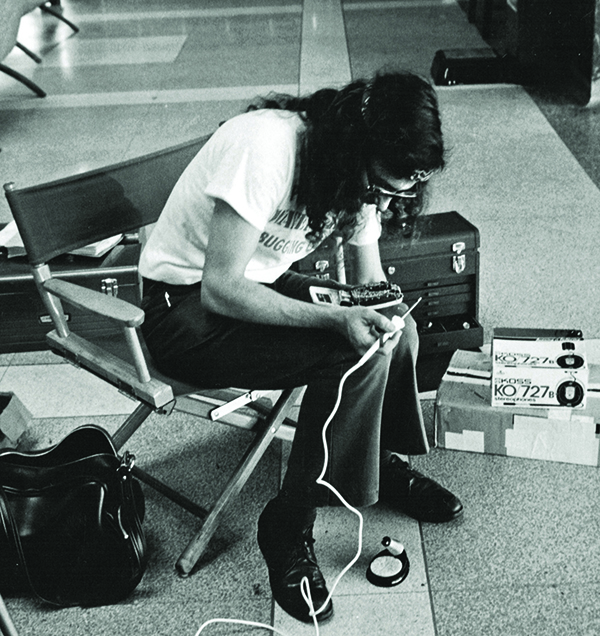

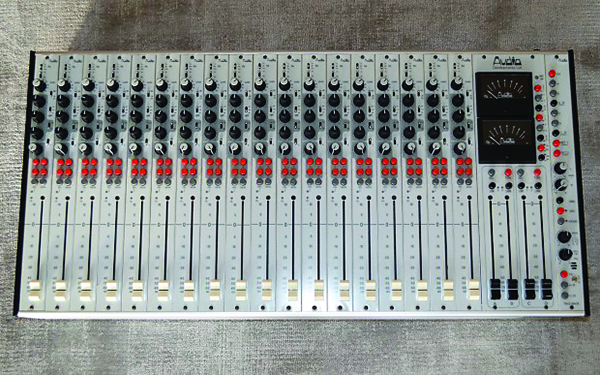

For Local 695 video engineers, whose responsibilities include media playback, off-camera recording, copying files from camera media to external storage devices, backup and redundancy creation, transcoding, quality control, syncing and recording copies for the purpose of dailies creation, this emerging technology presents an opportunity. Those who become well versed in its finer points will be ideally suited to jobs looking to take advantage of improved online distribution. While the need for traditional media managers who offload cards to hard drives is not going to disappear in the foreseeable future, a new breed of FTP media managers will become necessary going forward. Media managers who possess a basic understanding of network-attached storage (such as Avid’s Nexis or Pronology’s rNAS m.3) and common FTP client programs (such as Signiant’s Media Shuttle or Aspera’s Client) are ideally suited to take on these new roles as they become more prevalent.

In an ideal setting, a media manager is able to ingest/offload multiple streams of 4K media, perform transcodes if necessary, and then drop completed footage into what is called a “watch folder.” From there, the FTP client can parse the folder for any file containing a specific string of characters, such as the “.r3d” file extension of a Red camera or the identifying label of a particular camera. When it finds files that meet its criteria, the FTP client picks up the file and begins duplicating a copy of it to its web-based server. When the file has finished being copied to the cloud, the client software moves the original copy to a “transferred” folder in order to avoid sending the file multiple times. Signiant’s Media Shuttle is even capable of replicating folder structures, meaning that all of the organization and offline to online directories created on set by the media manager are retained when they are sent to post production.

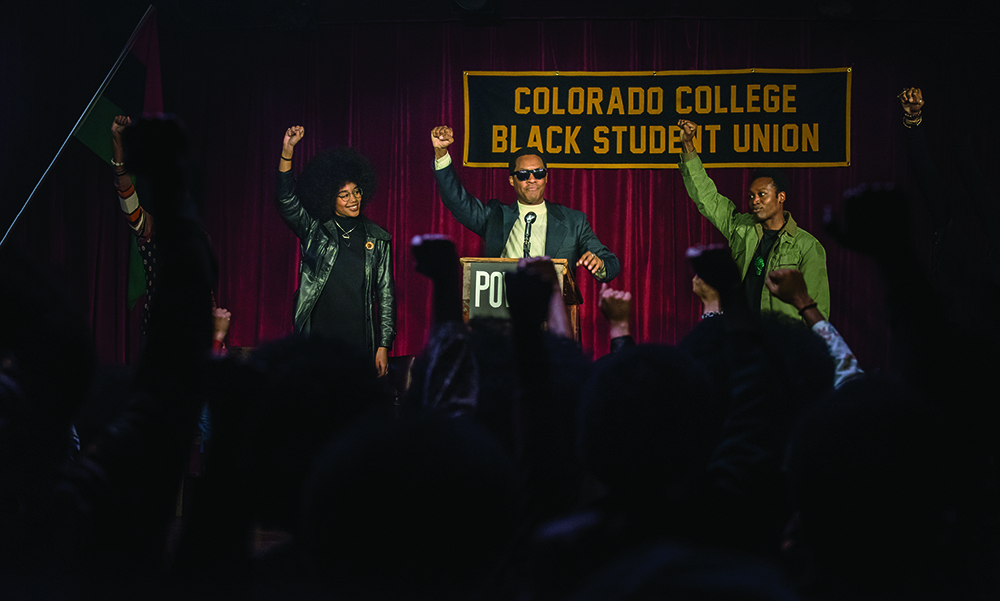

This sort of workflow has already been successfully carried out on shows such as MTV’s Wild ’N Out, MTV’s Video Music Awards, TED Conferences, and NBC red carpet shows. Wild ’N Out, in particular, is noteworthy for sending multiple episodes’ worth of content from Atlanta to New York on a daily basis during the production of its recent fourteenth season. In total, the show’s video engineers successfully transmitted fourteen cameras’ worth of video, amounting to more than twenty-five terabytes of data.

Nonetheless, this technology is not without its limits. In April of 2019, a team of astronomers successfully captured the first photograph of a black hole—a revolutionary feat that required more than five petabytes (or five thousand terabytes) of data to accomplish. Unfortunately, limitations in bandwidth and storage costs still meant that it was faster and more cost-effective to mail the physical drives back-and-forth across the globe than it would have been to upload the data to any online server. So for the time being, if a production has a few million gigabytes of data that they need to send out, it may be more efficient to physically transport the data back-and-forth.

Even limitations such as these are a temporary matter at best. As the nightly phone call was replaced by a single mass email, internet limitations will also disappear. Ten years ago, uploading even a terabyte of data to the cloud was a monumental task. As our industry continues to evolve and demand more efficient workflows for bulkier and higher resolution files, FTP clients will rise to the occasion. Ten years from now, it is likely that the threshold for transmitting a petabyte’s worth of data will be crossed. When that time comes, 695 video engineers should be prepared to jump at the opportunity for the new work created by this ever-evolving technology.